The return of the prophet

A writer’s ideas are his legacy. After he dies, it’s up to executors, heirs, lawyers, agents and colleagues to keep them alive -- and perhaps especially up to us, the readers, to thread those ideas through the weave of history, the passage of time, our own lives. Writers are the most potent of ghosts. Their spirits lodge in our quotidian decisions; we turn to them in times of change and times of terror. When their wisdom is unavailable, our choices get harder.

Aldous Huxley -- born in England in 1894, visionary author of 11 novels (most famously “Brave New World,” in 1932), seven short-story collections, seven books of poetry, three plays, two books for children and countless essays -- is there for us when we need him most. All his life, Huxley concerned himself with the most pressing issues facing humanity: environmental degradation, capitalist greed, totalitarian oppression, scarcity of resources, war, human cruelty and human potential. After his death -- on Nov. 22, 1963, the day JFK died -- his widow, Laura, tried to keep his memory and his work alive, but a perfect storm of factors -- personalities, family politics -- kept most of the work from getting the wide distribution and range of media it deserved.

In the last two years, all this has changed. With his estate finally in some kind of order, a movie of “Brave New World” is in the works, produced by George DiCaprio and starring his son, Leonardo, directed by Ridley Scott with a screenplay by Andrew Nicholls. The respected New York agent Georges Borchardt is shepherding new editions of his books and selling foreign rights to a world market hungry for Huxley’s work (especially those countries of the former Soviet bloc). We are, it is safe to say, on the eve of a Huxley revival.

Huxley was deliciously educated, prolific and prescient -- heir himself to a great torrent of ideas. His paternal grandfather was the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, defender of Charles Darwin when he needed it most. His mother was the niece of poet Matthew Arnold. Aldous was a member of the elite, educated at Eton and Oxford (Balliol). But he left the cocoon to become a true citizen of the world, keenly aware of its beauty and folly and fascinated by humankind’s self-destructive impulses. In 1937, five years after the publication of “Brave New World,” Huxley came to live in Southern California, like so many others for a combination of practical and spiritual reasons: the light (his eyesight was flawed from age 16), the desert air (his lungs were testy) and something unknowable as well. He lived in the Hollywood Hills -- with time spent at Llano in the Mojave Desert -- until his death. And what a beautiful death it was, as recorded in Laura Huxley’s book “This Timeless Moment.” More like a culmination ceremony, complete with LSD.

The house on Mulholland Drive, where both Aldous and Laura died (she late last year, at 96), is redolent of ideas, laughter and literature. Huge arched windows frame olive trees. Windows on the north face the Hollywood sign. Closets reveal stacks of translations of Huxley’s work. A safe holds tapes made in the days before his death. A room with windows on three sides (the “space room”) contains Laura’s inversion machine; one imagines such visitors as Daniel Berrigan hanging upside down. (“Did Laura ever hang you?” old friends ask each other.) Bedrooms with sleeping porches still contain the books, paintings and photographs Aldous and Laura enjoyed.

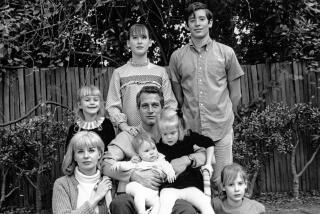

Piero Ferrucci, Laura’s nephew and one of three executors of the Laura and Aldous Huxley estate, is here from Italy to go through the alarming number of photographs and documents. He remembers Huxley walking around the grounds, looking, with his absurdly long legs, like a praying mantis. There is a photo of Piero as a baby; there is a photo of psychotherapist Roberto Assagioli (with whom both Piero and Laura studied) and Allen Ginsberg; there is a group photo with Linus Pauling, Richard Neutra, Christopher Isherwood, Gerald Heard, Aldous and his brother Julian on the terrace; there is a box containing an unpublished manuscript by Aldous.

Huxley arrived in Los Angeles with his first wife, Maria, who died of cancer in 1955; early friends included Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Anita Loos and the astronomer Edwin Hubble. That first house, also in the Hollywood Hills, burned down in 1961, along with Huxley’s letters from Bertrand Russell, D.H. Lawrence and others; running from the blaze, Laura and Aldous carried only her old violin and the manuscript of Huxley’s last novel, “Island.” By then, a new crop of unique intellectuals, fascinated by the human species and the planet -- John C. Lilly, Buckminster Fuller, Alan Watts and R.D. Laing, to name a few -- had found lively discussion in the Huxley home.

Daniel Hirsch, another executor of the estate, has spent several years trying to organize the papers and negotiate their sale to either the Huntington Library in San Marino or UCLA. He hopes those negotiations will be completed in the next few months. Aldous had a long-standing relationship with UCLA (which David Zeidberg, director of the Huntington Library, graciously has admitted) and a close friendship with Lawrence Clark Powell, longtime head of the UCLA libraries. Victoria Steele, head of special collections at UCLA, met with Laura before her death. She hopes the papers come to UCLA but is keenly aware of the work needed to organize and catalog the books, papers, tapes and ephemera. Steele has been in this business for many years, giving her a kind of equanimity, even when she wants something badly for UCLA. “Books have their own fate,” she tells me.

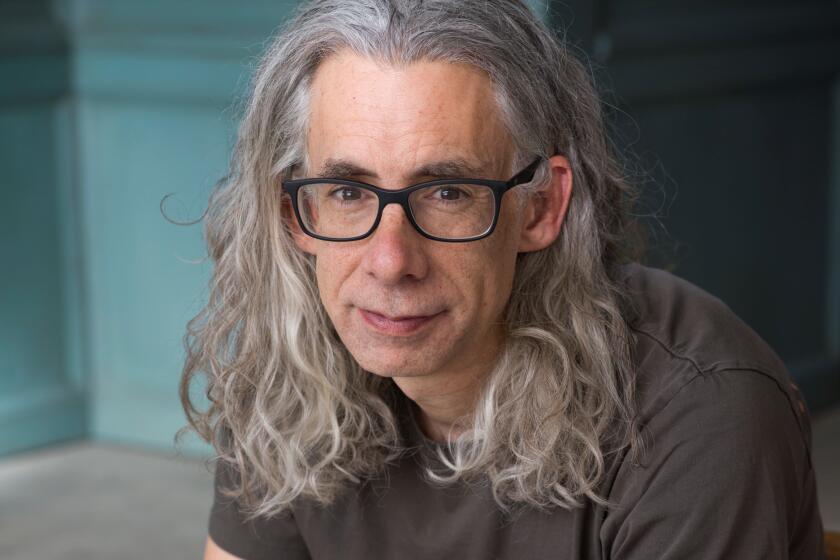

Hirsch is passionate about the Huxleys. “ ‘Island’ changed my life,” he says. “It’s the most important book I’ve ever read.” He plays me a tape of Aldous speaking at UC Santa Cruz about what the human race has done to the planet, about the beautiful cedars of Lebanon and the forests that preceded civilization. Huxley’s rich, deep voice fills the room. Laura Huxley was a concert violinist, a lay therapist and the author of several self-help books. Hirsch first met her in 1968, at a support group on anger she led in a public park in Beverly Hills. Participants would form a circle around one person and encourage him or her to let his anger out -- to scream. This attracted the attention of a policeman, who was invited to participate and declined, Hirsch explains, because he felt he had too much rage in him to be contained by a bunch of young hippies. Hirsch, who founded the Committee to Bridge the Gap (CBG), a nuclear watchdog group that monitors government radiation policy, was increasingly helpful to Laura as she grew older (though, he says, “she was running on all cylinders up until her last days”). She gave him responsibility for organizing the acquisition of the papers, and because its mission was so important to Aldous and Laura both, the proceeds of the sale will go to CBG.

Laura understood the need to organize her husband’s affairs before she died. The recent death of the Huxley estate’s longtime agent, Dorris Halsey, and of Huxley’s son, Matthew, changed the playing field considerably. Laura called on a friend, former Times Book Review editor Jack Miles, the third executor of the estate, to help find an attorney and a new agent. Miles contacted Borchardt and, to represent Laura and her trust, Los Angeles intellectual-property lawyer Jonathan Kirsch. (Full disclosure: Kirsch is a regular contributor to Book Review.) “Halsey was a character,” Kirsch remembers, “a unique personality of the old Hollywood.” Halsey, however, though Kirsch is too polite to say so, appears to have let things in the estate grow increasingly disorganized in her later years. “There was,” he admits, “no overarching strategic approach to promoting Huxley’s work and ensuring that he would reach new generations and a new audience.” (Today the team jokes, with some chagrin, about the presence of “ham sandwiches” in the files.) Negotiations began in earnest in January 2006, among Laura; Aldous’ grandchildren, Tessa and Trevenen (Matthew’s children with the first of three wives); and Universal Studios.

--

IT was Laura’s fervent wish that a major motion picture be made of “Brave New World” -- and also of “Island,” a tale of an isolated utopia. George DiCaprio, an old friend of Laura’s, has a deep understanding of and a passion for Huxley’s work. “Young people have always loved Huxley,” he says. “The best kind of people read him.” A calm but vivid figure, a man of little excess movement but great warmth, DiCaprio speaks of Huxley’s abiding belief in kindness and “the Fundamental All-Rightness” of the world.

One feels the ghost of Huxley, with all his height, intensity and Hollywood glamour, in the close connections among people who have taken his work to heart. Borchardt too, when asked about the specifics of his dealings with Laura before she died, speaks of the closeness he felt to her, the lack of need to spell out their common hopes for Huxley’s work.

And yet it has not been easy for all players in the Huxley estate to reach agreement over either the printed work or the films. Both grandchildren live on the East Coast. They did not grow up with Laura, but enjoyed cordial relations with her until a few years ago, when they began to express disappointment in the terms of Huxley’s will, which left Laura 80% of the proceeds of all copyright sales of Huxley’s work and Matthew the remaining 20% -- that portion went to Tessa and Trevenen after Matthew’s death in 2005. Under copyright law, the grandchildren had potential termination rights for some projects, including the movie, which meant that those contracts had to be agreed upon by all parties regardless of the percentage they were allotted in the will.

Filmmakers, burned in what is known as the “Rear Window” case (in which a literary agent who, for $650, bought the rights to the short story on which Alfred Hitchcock based his 1954 film, showed up to claim his share of the gross), insist in most deals that all parties with termination rights sign off on a project. Huxley had sold the film rights for “Brave New World” to now-defunct RKO; Universal Studios, which owns the British rights to the RKO library, needed the family to relinquish its termination rights. Tessa and Trevenen were reluctant to do so. With the help of Kirsch, Hirsch and film attorney Jay Dougherty, Laura secured their consent, allowing the movie to go forward. Royalty shares have been readjusted, and decision making streamlined and centralized in the Laura Huxley Trust. Borchardt, exuberant, has negotiated some 33 contracts around the world since, including a Canadian edition of “Brave New World” with an introduction by Margaret Atwood. (“I hope Laura is looking down on us and thinking good things,” he told me by phone from his New York office.)

Miles believes that one aspect of the Huxley oeuvre inadequately explored since his death is the fascination he felt for his chosen home, Southern California. He hopes that with new arrangements in place, there will be more freedom to explore that relationship -- perhaps with an anthology of Huxley’s writings on Southern California. Given the presence of the entertainment industry, Los Angeles might be considered ground zero for the hedonism, self-interest, image-making and greed Huxley believed would be our downfall. In Huxley’s alarums, Miles sees the intellectual foundations for later writers such as Neil Postman (“Amusing Ourselves to Death”). He points out that Christopher Hitchens, in his introduction to a recent edition of “Brave New World,” betrayed a shallow understanding of Southern California as a true source of inspiration to Huxley, referring to the writer’s 26 years here as a mere “Lawrentian sojourn.” In Britain, in fact, he was considered an American author.

Hirsch is happy that the negotiations with the family are resolved and Huxley’s work will be ever more available: “Aldous would be very pleased with how this has all sorted out. He had the extraordinary good fortune to have a wife who outlived him by 44 years and was dedicated to preserving his legacy. Now Laura has passed that task on -- to the DiCaprios; to Georges Borchardt; to Jonathan Kirsch; and to the team managing the literary trust: Jack Miles, Piero Ferrucci and myself. A major revival of interest in his ideas is coming, at a moment in history when it is critical for the world to hear his warning voice, his insights into and remedies for the human situation.”

After a moment, he smiles, perhaps remembering Huxley’s sense of “the Fundamental All-Rightness” of the world. “He would have laughed,” Hirsch says. “Now, finally, he is free.”

--

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.