WHISKEY REINVENTED

Who makes whiskey? A laconic Scot tending a still in the Highlands? A good old boy nursing his sour mash in Kentucky? A moonshiner brewing sneaky Pete up yonder in the holler?

They’re not the only kinds of whiskey makers anymore. Lately there’s been an explosion of handmade whiskey here on the West Coast. Forget Scotland and Kentucky -- we have a crop of eager Western dudes who want to create a distinct Western style of whiskey.

They’re taking this nouvelle whiskey idea in wildly differing directions -- rough and powerful, sweet and fruity, gnarled and smoky, mellow and harmonious. The result is whiskeys with very distinct personalities, whiskeys you don’t find anywhere else.

In the last few years six distilleries have started making and selling whiskey in California and Oregon, and two more will join them in the next year or so. An equal number of outfits up and down the coast are eyeing the idea. Already we have three times as many (legal) pot-still distilleries as the rest of the country combined.

Easterners may be puzzled. The West Coast is known for lighter drinks -- beer and wine. In fact, that may be exactly why small-batch whiskey is happening here. “West Coast consumers are more receptive to craft whiskey,” says Lee Medoff of Edgefield Distillery near Portland, Ore. “They’ve grown up with wineries and microbreweries.”

A distinctive process

Most of the world’s whiskey is made in high-volume continuous stills that can produce thousands of gallons a day. The West Coast craft whiskey movement has gone back to the antique pot still, which is more labor intensive and a lot less productive, yielding perhaps five gallons per batch. But it produces a more distinctive result, which is why single-malt Scotch has always been pot-distilled.

The whiskey makers come from two quite different traditions. There are brewers -- down-to-earth guys from craft breweries who know their grains -- and there are makers of European-style fruit brandy (eau de vie), with its goal of preserving delicate fruit flavors through the brutal process of distillation.

The transition to whiskey is attractive for an eau-de-vie distiller -- he just contracts with a brewery to deliver a batch of beer made to his specs and then distills it. Now the distillery needn’t have a down season; you can make whiskey all year round, even when there’s no fresh fruit.

On top of that eau de vie is a narrow, exotic sliver of the American beverage market, whereas whiskey is already familiar to the public.

For brewers, the transition is much more involved. They have all the mysteries of the still to master, and their taxes and insurance will go up once they become distillers (beer isn’t a fire hazard, but 124-proof whiskey is). The biggest problem is warehouse space -- unlike beer, which you can sell as fast as you make it, whiskey has to be aged for years.

St. George Spirits, on Alameda Island in the Bay Area, has roots in both traditions and shows the unprecedented possibilities of a new approach to whiskey. Master distiller Jorg Rupf comes from generations of eau-de-vie distillers in Germany; assistant distiller Lance Winters was a brewer before he joined in 1995. The product of their collaboration is like no other whiskey ever -- it has a rainbow of sweet fruit and flower aromas you can scarcely believe come from grain, and an amazing smoothness on the palate.

Best known for its Hangar One Vodka, the distillery is in a striking location: an isolated airplane hangar in the former Alameda Naval Air Station. From its back door there’s a picture-postcard view of San Francisco.

Rupf and Winters use a mixture of the toasted malts that give color and flavor to darker beers such as porter and stout; they’re the only West Coast distillers to do so. Perhaps this is where their whiskey gets the striking fruit aromas that make it so distinctive. (Their use of Bourbon barrels also explains some of its sweetness.) They also include some smoked malts -- not smoked over peat, as for Scotch, but over hardwoods such as beech and alder.

Another San Francisco company, Anchor Brewing Co., made the first of these West Coast whiskeys: Old Potrero. Anchor’s owner, Fritz Maytag (whose family created both Maytag washers and Maytag blue cheese), has a track record of turning out excellent products by revitalizing old-fashioned, small-scale production techniques. His Anchor Steam beer was instrumental in reviving craft beer brewing in the 1970s.

Around that time, he was intrigued to read that 200 years ago, most American whiskey was rye (see “Heads, Tails of Making Whiskey”), sold straight from the still without barrel aging. He decided to set about rediscovering the sort of whiskey George Washington made: 100% rye.

“There was an opportunity here to step in,” Maytag says, “on a tiny little scale, the way we did with beer, taking very traditional attitudes but with modern food processing knowledge.” He made his first whiskey in 1993.

Maytag bottles his whiskey the old-fashioned way, at the same strength as it comes from the still: 124 proof. Because of post-Prohibition laws, he has not been able to sell it without aging it, as he originally envisioned, but he does release one version (which, under California law, he can only call “spirit,” not whiskey) aged only two years. Another is aged three years in charred Bourbon-type barrels.

“It’s a pilot project, a research project,” Maytag says. “Mind you, I hope it will grow.”

His whiskeys, particularly the minimally aged “spirit,” are powerfully flavored and might make people reevaluate the lost taste for rye whiskey -- and the current craze for aging. His youngest bottling has fascinating fresh flavors that years in the barrel can only muffle.

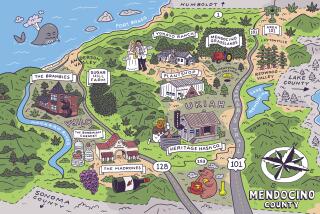

The other Bay Area whiskey maker is Domaine Charbay, long known for its high-end brandies and eaux de vie made at a small vineyard in the hills above Napa Valley. (It also has a larger distillery in Ukiah.)

Though the Karakasevic family have been distillers for 13 generations, that doesn’t mean Charbay is old-fashioned. “I didn’t want to make a Bourbon, and I didn’t want to make Scotch,” says Marko Karakasevic. “I liked the idea of adding hops, as in beer.” A few Bourbon makers use hops, but other West Coast distillers have rarely tried making hopped whiskey.

Karakasevic ages his whiskey in Bourbon-type charred barrels. His first batch, released at 5 years, sold in an eye-catching etched bottle, at a startling 129.4 proof and a staggering price: $325. It is a majestic whiskey, tasting of butterscotch and vanilla with apple fruit, but the main impression is of solidity, harmony and concentration, like a great big bull’s-eye.

Next year Karakasevic plans to release a version rectified to the industry standard of 85 proof at a price closer to earth: $85.

West Coast movement

In a far less romantic location -- an industrial park in Irwindale -- is St. James Spirits, the only one of these distilleries in Southern California. In this homely room, Jim Busuttil -- by day a science teacher in El Monte -- turns out a variety of unusual and very professionally made liquors, including cherry brandy and a tequila equivalent aged in French oak.

His whiskey, Peregrine Rock, is another West Coast experiment in combining Bourbon and Scotch techniques. The malt comes from Scotland and is lightly peated, but the whiskey is aged partly in new Bourbon barrels. It has some of the fruitiness of the St. George, but its wry edge of smoky flavor makes it feel like a traditional whiskey style -- from some undiscovered land. Though Busuttil’s plant is a small one, he has a substantial inventory of aging whiskey.

Currently two operations are making whiskey in the Portland area. Clear Creek Distillery, Stephen McCarthy’s eau-de-vie distillery, was the second to make a West Coast whiskey. In 1994 McCarthy ran out of fruit and began using a mash brewed for him by neighboring Widmer Bros. Brewery using peat-smoked barley imported from Scotland. McCarthy’s whiskey is emphatically Scottish in the most uncompromising style: You’d think it was an ultra-peaty Islay malt like Lagavulin or Laphroaig. Even so, he’s not strictly imitating Scotch. After aging his whiskey two or three years in used sherry barrels, as would be done in Scotland, he finishes it in new barrels of Oregon white oak for six to 12 months.

“Oregon winemakers tried white oak for a while,” he says, “but they concluded it wasn’t suitable for wine. I tried it as a lark and decided I liked what it did to the whiskey -- it gave it a richer, more complex character.”

Edgefield Distillery in Troutdale, Ore., is the crown jewel among the 50-odd brew pubs, restaurants and inns run by the McMenamin brothers in Oregon and Washington. Distiller Lee Medoff, a former brewer, enjoys a unique luxury -- built-in demand. Other distillers struggle to get distributors, but Medoff just sends his product to the company’s pubs. “The public has been very receptive,” he says. Medoff uses malted barley but ages the whiskey in new Bourbon barrels. His standard product Hogshead is an unpretentious 3-year-old, smooth and light like a young Bourbon, but not as sweet. Next year he will release a richer 5-year-old.

The West Coast whiskey movement continues to grow -- Lagunitas and Sweetwater, two distilleries in Petaluma, Calif., currently have whiskey aging. Fish Tale Ale in Seattle is serious enough about getting into distilling to have gotten a Washington state law changed. An outfit called Glenkelley plans to build a distillery near Yosemite where it will even grow its own barley.

The obvious, most lucrative drink for craft distillers to make is flavored vodka, the trendiest spirit of our age. Several do.

Then why make whiskey too? Clearly, it’s the allure of creating rare and sophisticated flavors from something as mundane as grain. It’s alchemy, bro.

So is locally made whiskey the next big thing?

Time will tell. But the enthusiasm of this new wave of whiskey distillers, and the remarkable potential they’ve shown, bode well for it.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Heads and tails of making whiskey

Barley is the basic grain of most beer and whiskey. In Scotland, some barley malt is smoked over peat fires to give a rugged, smoky flavor, which is an acquired taste. Rye was the standard American whiskey grain for centuries.

Bourbon is made from a mixture of grains; by law, corn must be at least 51% of the mix. Unique among the world’s whiskeys, Bourbon must be aged in new oak barrels, charred on the interior, for a minimum of three years. Bourbon doesn’t have to come from Kentucky -- it can be made anywhere if it follows these rules.

Before it can be fermented, the starch in grain must be broken down into sugars, which is accomplished by letting it sprout. The sprouted grain, known as malt, is boiled to dissolve its sugars, and this liquid is fermented into beer.

Distilling consists of heating this beer (“wash”) to drive off alcohol and other volatile compounds, which are then forced through water-cooled pipes where they condense. The first and last fractions (“heads” and “tails”) are discarded, and the “heart” is barreled and aged.

Originally whiskey was not necessarily aged, but after Prohibition, federal and state laws required whiskey to be aged two years to be labeled as such.

-- Charles Perry

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Shot for shot,

West Coast-style

The Times tasting panel met recently to sample seven West Coast whiskeys. On the panel were columnist Russ Parsons, staff writer Corie Brown, food editor Leslie Brenner and deputy features editor Michalene Busico. We were struck by the generally very high quality and the wild diversity of styles. All were tasted straight and then with a little added water.

All these whiskeys are in limited supply, and Hogshead is not currently sold in California.

The whiskeys are listed in order of the panel’s preference.

St. George Single Malt. The panel’s clear favorite, this 86-proof single malt showed delicate fruit aromas of orange blossom, litchi, tangerine and roses; its nose reminded us more of an Alsace Gewurtztraminer than a whiskey. Smooth on the palate, with a hint of peppermint on the finish. Available at the Wine and Liquor Depot in Van Nuys, about $40.

Charbay Double Barrel Hop-Flavored Whiskey. An impressive, elegant whiskey -- harmonious, rounded and focused at 129.4 proof. With attractive dry grass aromas -- like standing in a field of hay -- and a pleasantly bitter finish, this spirit is high-definition, with no background noise. Available at Wally’s Wine & Spirits in Los Angeles and Hi-Time Wine Cellars in Costa Mesa, about $325.

Old Potrero Single Malt Spirit. Aged only two years, this 124-proof spirit from Anchor Brewing Co. is bracingly alcoholic at first, then surprisingly sweet and smooth, with floral, spicy aromas typical of rye whiskey. A little added water increases the impression of sweetness. Available at Hi-Times and Mission Liquors in Pasadena, about $65.

Peregrine Rock California Pure Single Malt Whisky. With aromas of sweet fruit and smoke from lightly peated malt, St. James Spirits’ 80-proof whiskey is round and smooth, with a sweet, complex finish. Sometimes available at Red Carpet Wine in Glendale, about $21 for a 375 milliliter bottle.

Old Potrero Straight Rye Whiskey. Aged for three years, this 124-proof rye is velvety, with complex caramel flavors. Its aroma reminded the panel of a brandy-based liqueur such as B&B.; With added water, notes of fresh hay come to the fore. Available at the Wine House in West Los Angeles, Hi-Times, Mission Liquors and the Wine and Liquor Depot, about $60.

McCarthy’s Oregon Whiskey. An aggressively smoky, peaty 80-proof whiskey from Clear Creek Distillers, with an iodine nose much like an Islay malt such as Lagavulin. The panel members who were fond of this style found it pleasing; others compared it to burnt rubber. Available at Wally’s, the Wine House and the Wine and Liquor Depot, about $35.

Hogshead Whiskey. A respectable 92-proof whiskey for mixing, not for sipping. Made by Edgefield Distillery and available only in Oregon and Washington state, about $32.

-- Charles Perry

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.