Benefits of HPV vaccine questioned

New data on the controversial HPV vaccine designed to prevent cervical cancer have raised serious questions about its efficacy, researchers reported today, potentially undercutting the efforts in many states to make vaccination mandatory.

Although the vaccine, called Gardasil, blocked about 100% of infections by the two human papilloma virus strains it targets, it reduced the incidence of cancer precursors by only 17% overall.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 11, 2007 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Friday May 11, 2007 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 37 words Type of Material: Correction

HPV vaccine: An article in Thursday’s Section A about studies on human papillomavirus said that one by Johns Hopkins University researchers looked at 100 women with newly diagnosed throat cancers. The 100 patients were men and women.

Part of the reason was that many of the teenage girls and young women in the three-year study had already been exposed to the virus, according to the report in the New England Journal of Medicine.

But the data also hinted that blocking the targeted strains might have opened an ecological niche that allowed the flourishing of HPV strains previously considered to be minor players, partially offsetting the vaccine’s protection.

In an editorial in the same issue of the journal, Dr. George F. Sawaya and Dr. Karen Smith-McCune of UC San Francisco called the benefits of the highly touted vaccine “modest,” and said that young women and their parents should take “a cautious approach” to vaccination because of the many unanswered questions about its efficacy.

“The effect is fairly small,” Sawaya said in a telephone interview. “The recommendation for widespread vaccination of women after they become sexually active may need to be rethought.”

The maker of the vaccine, Merck & Co., said the studies clearly showed that the vaccine prevented infections from the two HPV strains and reduced the number of precancerous lesions caused by the them.

Initial optimism

Gardasil was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in June amid cheers that it could largely prevent cervical cancer among vaccinated women.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quickly recommended that all girls and women ages 11 to 26 receive the vaccine.

The American Cancer Society seconded the recommendation, although it concluded that there was “insufficient evidence” of benefit among women ages 19 to 26 because so many had already been exposed to the virus.

At least 24 state legislatures have introduced bills calling for mandatory vaccination of girls in their early teens or younger.

A bill was introduced in California, but its prospects are uncertain because of complaints from parents that vaccination may encourage sexual promiscuity.

The debate over mandatory use of the vaccine has been further complicated by the relatively high cost of the treatment, about $360 for the vaccine plus the cost of three office visits.

Immunologist W. Martin Kast of USC’s Keck School of Medicine, who was not involved in the research, said he thought the study had not gone on long enough to prove the vaccine’s worth.

“In a three-year follow-up, it is very hard to reach statistical significance in a disease process that takes about a decade to fully develop,” he said. “Thus, it is not fair to state that the vaccine is not effective. It will be, but it needs more time to materialize.”

Cervical cancer kills about 3,900 U.S. women each year, a number that has been reduced substantially by widespread Pap screening. But Pap testing is not affordable in many parts of the world, and the disease kills at least 250,000 women globally each year.

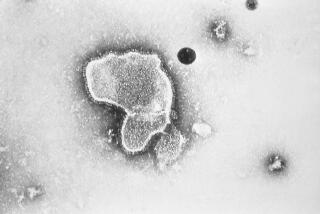

The cancer is caused primarily by the human papilloma virus. About 20 strains of the virus are known.

Gardasil targets two of them -- HPV-16 and HPV-18 -- that normally produce about 70% of the cancers. It also prevents infections from two other strains of the virus that produce about 90% of all genital warts.

Merck has so far distributed more than 4 million doses of the vaccine, and early results indicate that it is safe. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals has a similar vaccine, called Cervarix, that immunizes only against types 16 and 18. It has been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for approval.

In a trial sponsored by Merck, epidemiologist Laura A. Koutsky of the University of Washington and her colleagues studied 12,157 women between the ages of 15 and 26, half of whom were given Gardasil in the recommended three doses over six months and half of whom were given a placebo.

All the subjects were followed for three years, with investigators looking for precancerous lesions that have a high likelihood of progressing to full-blown cancer. Such lesions are normally surgically removed when they are detected by a Pap smear.

Among women who had not previously been exposed to types 16 and 18, the vaccine reduced the risk of precancerous lesions caused by those two strains by 98%.

“The overall message, in my mind, is that among susceptible young women, the vaccine was highly effective in preventing HPV-16 or -18 precancerous cervical lesions,” Koutsky said.

When the researchers included all the women enrolled in the study, the vaccine reduced the risk of lesions caused by types 16 and 18 by 44%.

The number of women who were previously infected by the viruses was not large enough to account for this low rate of protection.

But when Koutsky and her colleagues considered lesions caused by all strains of the virus, the vaccine reduced the risk by only 17%.

Because researchers had previously believed that 50% of all serious precancerous lesions were caused by types 16 and 18, this rate of protection seemed inexplicably low.

Sawaya suggested in the editorial he co-wrote that the small size of the protection could be because other strains of HPV are filling the gap when types 16 and 18 are eliminated.

Dr. Douglas Lowy of the National Cancer Institute, who originally developed Gardasil, noted that even if the other types proliferate, there might not be a significant increase in cancers because the other strains are less carcinogenic.

If the other strains are, in fact, proliferating, USC’s Kast said, “then the addition of other HPV types to the vaccine would be a logical option.” Merck and GlaxoSmithKline are working on that.

Koutsky noted, however, that 17% was an improvement over the 13% figure that was presented to the FDA more than a year ago, which resulted in the administration’s approval.

As time proceeds, she speculated, the gap between the protected and unprotected women would continue to grow.

Falling short

Overall, the new results indicate that the vaccine is not living up to its initial prospects. The findings show that 129 women would have to be vaccinated to prevent one precancerous lesion.

When doctors give the vaccine to patients, they think that “ ‘I am protected against everything,’ and that’s just not true,” said Dr. Diane M. Harper of Dartmouth University, who helped design a related Merck-funded HPV study in the journal.

She is still in favor of giving Gardasil to girls because it is safe and it “protects against the main HPV bad actors,” but she argued that neither doctors nor women should be lulled into a false sense of security by the shots.

“I don’t think this is the gun that is going to take cervical cancer off the map,” she said.

Dr. Ursula Matulonis of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said the data supported the accepted position among doctors that the vaccine should be given to girls before they become sexually active.

In another related study in the journal, researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore looked at 100 women with newly diagnosed cancers of the back of the throat.

The researchers found HPV in nearly three-quarters of the tumors. They found a strong association between the infections and oral sex.

The finding suggests that the vaccine might also prevent these cancers, although that possibility has not been studied.

*

jia-rui.chong@latimes.com