From Donald Duck to Donald Trump, an unprecedented look at Latin American art holds up a mirror to the U.S.

So much about the tangled relationship between the United States and Latin America can be told through a surprising cultural character: Donald Duck.

The many lives of the hotheaded fowl serve as a curious case study on the enduring cultural links between the U.S. and Latin America. These links will surface repeatedly over the course of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, the series of art exhibitions across Southern California that officially debuts next week.

Donald Duck, star of the new PST: LA/LA exhibition “How to Read El Pato Pascual: Disney’s Latin America and Latin America’s Disney,” was created by Walt Disney and his animators in the company’s Silver Lake studio in the early 1930s. By 1937, he was headlining his own animated short: “Don Donald,” in which he plays a hapless caballero in a stereotypical Mexican town, complete with cactus and recalcitrant burro.

Donald’s dip into Latin American culture didn’t end there. In 1941, Disney took a tour of Latin America as part of a U.S. government effort to build solidarity in the Western Hemisphere during World War II. That journey inspired a pair of films that now serve as notable artifacts of the era of Good Neighbor policy: “Saludos Amigos” and “The Three Caballeros,” the latter of which features the hallucinatory convergence of Donald Duck cavorting with folksy Latin American locals and Busby Berkeley-style dance numbers.

“It’s like a hall of mirrors,” says Jesse Lerner, who with L.A.-based artist Rubén Ortiz-Torres curated “How to Read El Pato Pascual,” which is set to open Sept. 9 at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in West Hollywood and the Luckman Fine Arts Complex at Cal State L.A.

“Disney borrows from Latin America, they turn it into something Hollywood, they send it back to Latin America, and the Latin Americans do something else with it and send it back.”

Disney characters have inspired bootleg T-shirts, critical theory and indigenous dances. For decades, Donald Duck served as a logo for the Mexican juice company Refrescos Pascual. (It now has its own duck, Pato Pascual, who sports a baseball cap.) And Donald was at the heart of the seminal leftist essay, “How to Read Donald Duck,” published in 1971 by Chilean-Argentinean thinker Ariel Dorfman and Belgian sociologist Armand Mattelart, who present Disney comics as ideological tools of capitalist propaganda.

Disney appropriates and the people appropriate Disney. It’s a constant dispute.

— Rubén Ortiz-Torres, artist and curator

One scholar has even theorized that Donald Duck may have been inspired by indigenous Latin American culture to begin with. Disney did not have an official comment on the matter, but as the story goes, an artist who worked for Diego Rivera gave a lecture on Mexican art to a group of employees at Disney Studios in the early 1930s. Among the visuals, there may have been an image of a pre-Columbian duck vessel from Colima. Made hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, it resembles a wide-eyed duck wearing what appears to be a small beanie.

“Disney appropriates and the people appropriate Disney,” says Ortiz-Torres. “It’s a constant dispute.”

It’s a similar back-and-forth that reflects the broader cultural exchange between the U.S. and Latin America, a relationship that over the decades has swung from fraternal to fraught and back again.

PST: LA/LA, which focuses on the work of Latin American and U.S. Latino artists, will examine this relationship in many ways. And it will be no small affair.

Funded by the Getty Foundation to the tune of $16 million, the series consists of dozens of exhibitions and events at more than 70 Southern California institutions, plus complementary programs at more than 65 commercial galleries. A launch party in Grand Park, a Latin music concert at the Hollywood Bowl (including Café Tacvba, Mon Laferte and La Santa Cecilia) and a contemporary music series at Walt Disney Concert Hall are also part of the lineup.

As the shows prepare to shine a light on the cultures of Latin America, they also will serve to hold up a mirror to the United States.

The shows touch on pre-Columbian artisanry, the U.S.-Mexico border, Chicano queer identity and the Asian diasporas of Latin America. Not to mention the “Pato Pascual” exhibition, which examines the potent repurposing of the world’s most iconic cartoon characters.

RELATED: How Mexico's 'Radical Women' are rewriting the history of Latin American art »

This all unfolds in a climate of intense anti-immigrant sentiment — from Donald Trump’s reference to Mexican immigrants as “rapists” during his 2015 campaign kick-off speech to the recurring nativist refrain of “build the wall.” Just this week, the Trump administration put an end to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which shielded young adults brought to the U.S. illegally as children from deportation.

“This was not anything that we anticipated six years ago when we started talking about this edition of Pacific Standard Time,” says Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “But now that it’s here, it highlights the truth about borders — that they are political creations that don’t fit neatly on cultural populations.”

As the shows prepare to shine a light on the cultures of Latin America, they also will serve to hold up a mirror to the United States. First, because the Latino presence is so critical in the U.S., the second-largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. And because to be Latin American, in some ways, is to continuously contend with the outsize presence of the United States.

Among the tropes artists will be dismantling are what Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Rita Gonzalez describes as the “entrenched notions of American exceptionalism.”

“This is 2017 and we are just catching up with Latin American art,” Gonzalez says. “And it is part of the history of the Americas, just like the United States is part of the history of the Americas. You’ll see that manifesting itself in these shows.”

Gonzalez co-curated LACMA’s “A Universal History of Infamy,” which opened late last month as an early entry in the PST: LA/LA series. It features the work of 16 contemporary U.S. Latino and Latin American artists whose work touches on a range of global concerns.

We are just catching up with Latin American art. It is part of the history of the Americas, just like the United States is part of the history of the Americas.

— Rita Gonzalez, curator

One project on view at the LACMA show, by Carolina Caycedo, a Colombian artist now based in Los Angeles, examines the nature of dam-building projects in Latin America — one of which, the Quimbo Dam on the Magdalena River, is located in the region her family is from.

In a video installation, she pairs views of rivers in natural and dammed states. On a table, a long, accordion-style book — which unfolds in the shape of a river — meanders through the gallery.

“We are building so many dams in South America, but decommissioning dams in the United States — so what does that mean?” she asks, sitting amid fishnet sculptures in her downtown Los Angeles studio. “It makes you think about energy slavery in the future. Will we bear the environmental consequences for energy production that will be consumed here in the United States?”

With the project, Caycedo aims to show how a dam in rural Colombia might link up with a light switch several nations away.

This notion of inter-connectedness, of the U.S. not being able to separate itself either physically or psychologically from the rest of the Americas, comes up in other exhibitions too.

“Video Art in Latin America,” which goes on view at LAXART in Hollywood Sept. 17, is part of an exhaustive effort by the Getty Research Institute to compile Latin American video art back to its origins.

In a work titled “They Call Them Border Blasters,” from 2004, Mexican conceptual artist Mario García Torres explores the U.S. radio stations that position themselves on the Mexican side of the border in order to skirt U.S. regulation. The border’s hard dividing line may limit human movement, but geographic proximity means that radio waves can travel back and forth unimpeded.

Even as it continuously looks to Europe, the United States is firmly part of the Americas.

It highlights the truth about borders — that they are political creations that don’t fit neatly on cultural populations.

— Jim Cuno, J. Paul Getty Trust

“We are more similar to Latin America than we are to Europe,” says the show’s co-curator Glenn Phillips. “These are countries that have vast histories of migration, of slavery — there are so many parts of post-colonial history that are shared across the Americas and that the U.S. often thinks of itself as being apart from.”

And as the U.S. enters a period of profound self-questioning — of its culture, its institutions and its politics, the exhibitions of PST: LA/LA will provide an intriguing view of how Latin American societies have contended with these very same issues.

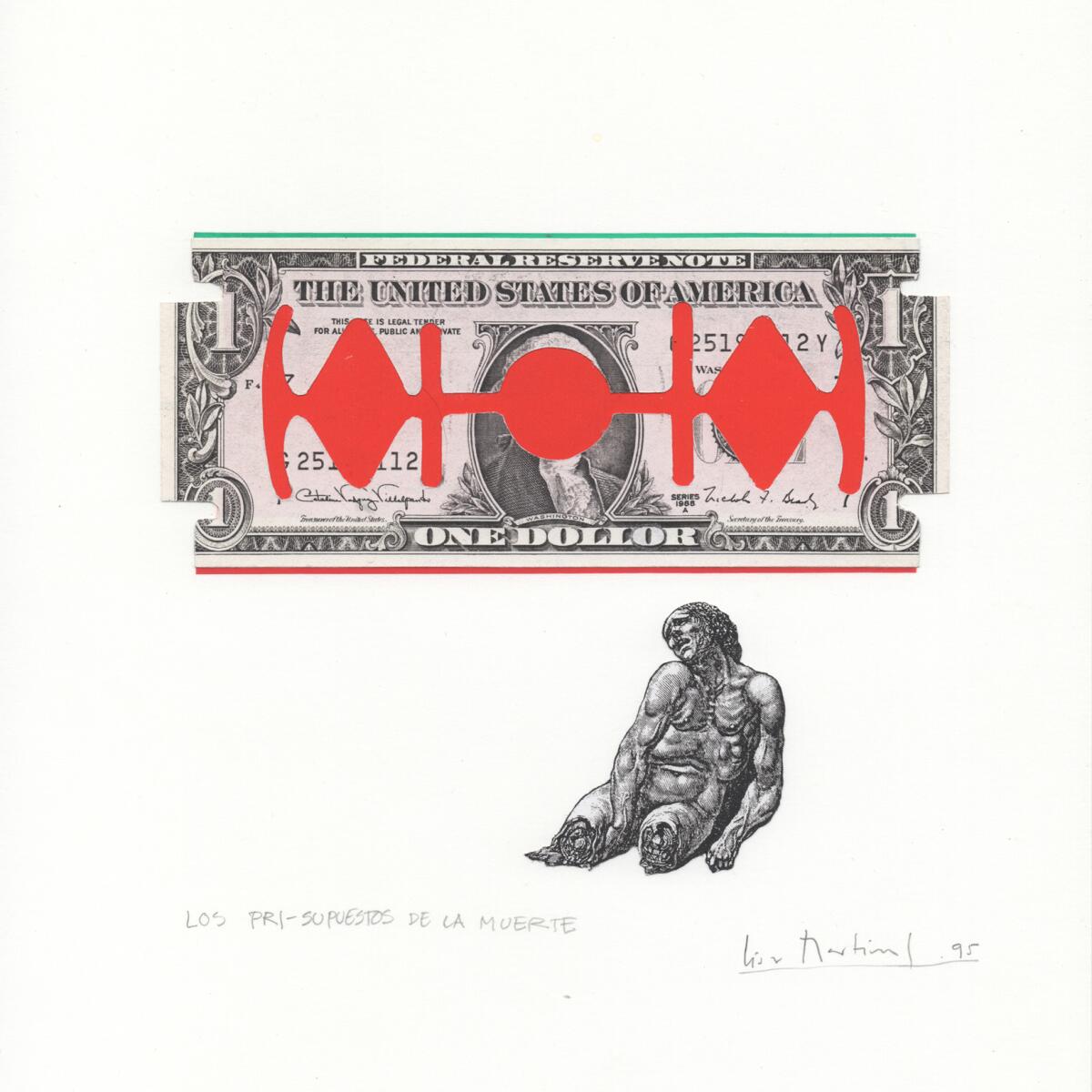

“Below the Underground: Renegade Art and Action in 1990s Mexico” is scheduled to open at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena in the middle of October. It features experimental works of installation and performance by Mexican artists reacting to a period in which that country’s institutions had been weakened.

“In the 1990s, the artists we are looking at were responding to a climate that was dire in many ways,” says exhibition curator Irene Tsatsos. “There was a crisis in Mexico’s political system, an economic crisis, violence was everywhere, the drug trade was rampant and there was inadequate infrastructure in many respects. All of these things called upon citizens to perform, to come together in previously unforeseen ways. Artists were part of that.”

During that time, the collective Pinto mi Raya (which consists of Mónica Mayer and Victor Lerma), invited museum-goers to respond to a question about what steps they would take to achieve democracy and justice. “Justicia y Democracia” was first shown in Mexico in 1995. It will be reinstalled at the Armory Center, where visitors will be invited to post their replies — a timely work.

Also timely are many of the exhibitions featuring the work of U.S. Latino artists, a population that has long contended with issues of equity and representation.

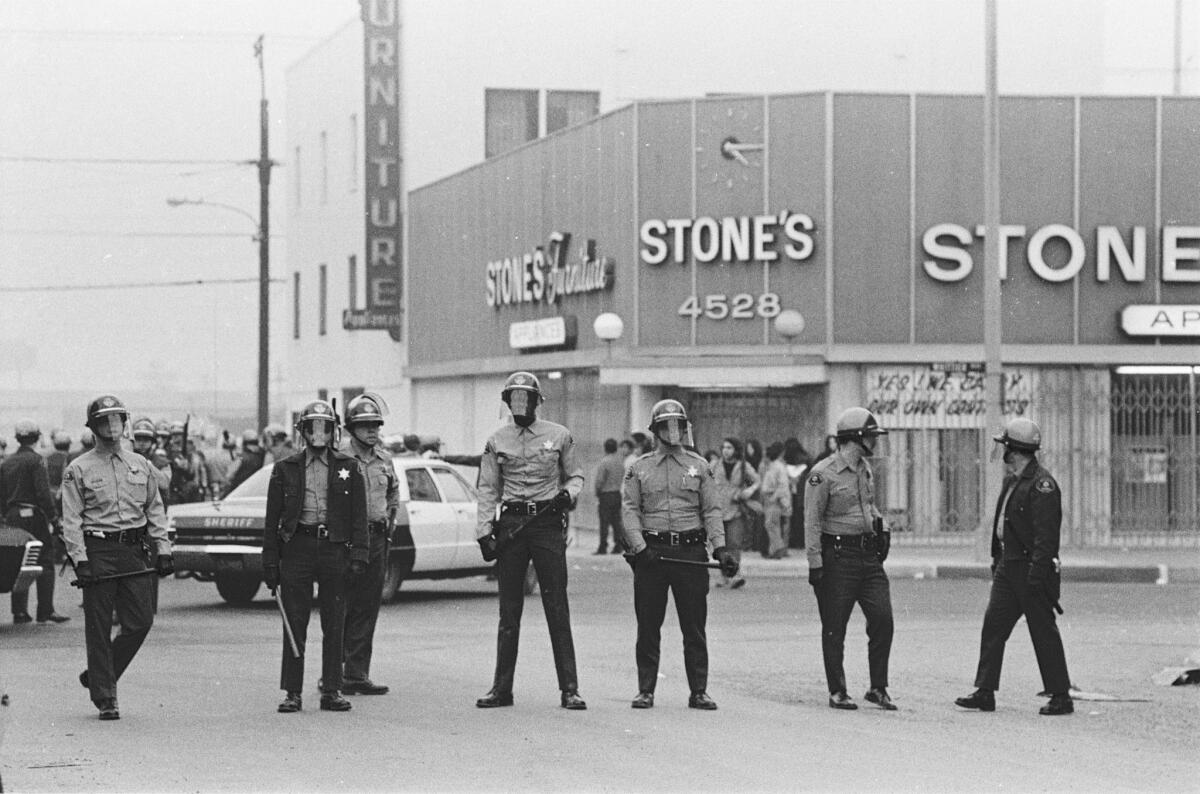

The exhibition “La Raza” will reflect this. The show draws from a vast archive of photographs from the Lincoln Heights-based Chicano activist newspaper and will go on view at the Autry Museum of the American West on Sept. 16. The images chronicle issues of policing, civil rights and labor struggle.

“‘La Raza’ speaks through time of issues that have yet to be resolved: of work, of indigenous rights, of migration and immigration, of demanding access to a system that has typically denied access,” says Luis Garza, a former “Raza” photographer who serves as co-curator of the exhibition. “But 50 years past is present and is future. The very nature of what is contained in those photographs reflect what is going on in the country today.”

Fifty years past is present and is future.

— Luis Garza, photographer and curator

Most significantly, the very nature of the Getty’s PST: LA/LA project — with its sprawling exhibition program and its countless curatorial points of view — mean that the art of the continent will not be subject to a single defining conclusion.

“It’s so decentralized and so chaotic and everybody does their thing,” Ortiz-Torres says. “If the Museum of Modern Art did this, it would be, ‘These are the guys to follow. This is the canon.’ The thing I like about the Getty is that you will have these competing visions and they will force us to make sense of what’s going on.”

For Latin American art in the U.S., a rare moment of texture and nuance — one that may reveal something important about ourselves.

This story is part of our Fall 2017 arts preview. See our complete coverage here.

Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA

Where: Museums and galleries all over Southern California

When: Most exhibitions open on the weekend of Sept. 16 and run through the fall

Info: pacificstandardtime.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO:

Firecrackers, a striptease scandal and more moments of change from the Hammer's 'Radical Women'

Argentine slums and a Unabomber cabin: How 'Home' at LACMA rethinks ideas about Latin American art

More than 65 art galleries to join PST LA/LA museum exhibitions with Latino and Latin American shows

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.