Column: The Toyota effect: 30 years later, one man’s acoustic designs still rule how we hear music

It all started in a city with a taste for single malt whiskey and classical music — and an obliging beverage company. Suntory Hall opened here 30 years ago, transforming the musical — and to some extent city — life of Tokyo and leading to a concert hall building boom that extended throughout Japan and eventually the world.

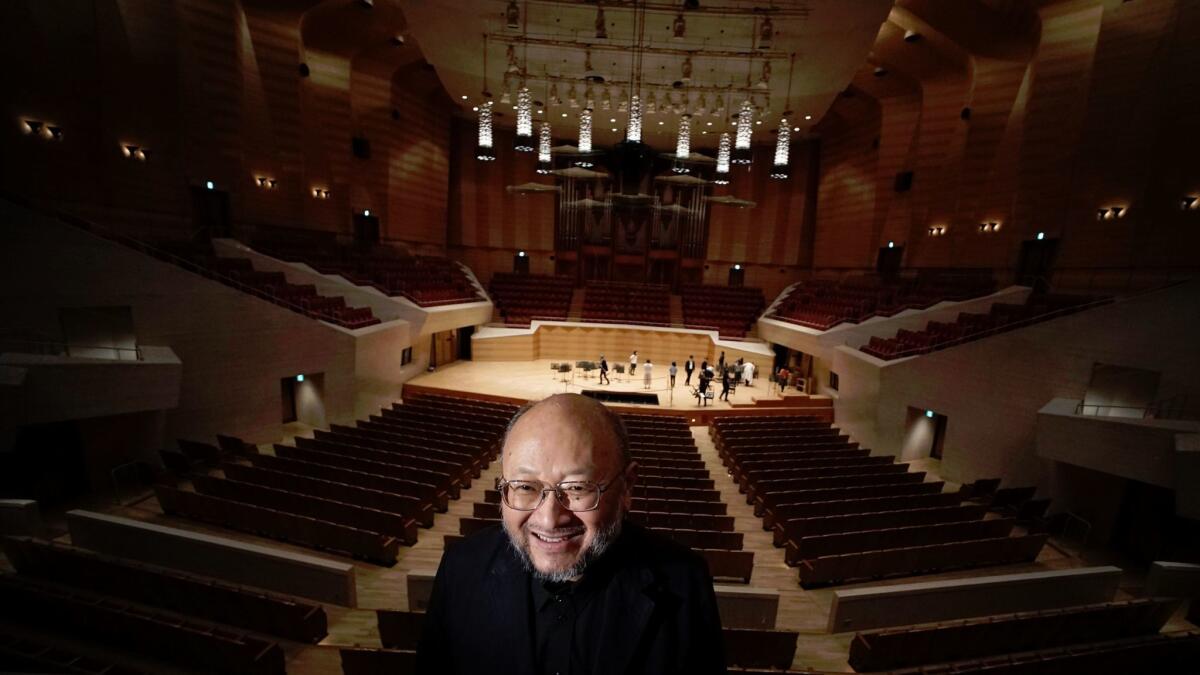

Suntory, tucked away in a fancy shopping complex, makes no statement on the street, as you might expect from its corporate benefactor. The statement was left to a young acoustician named Yasuhisa Toyota, who put the listener in the middle of the music. This was Toyota’s, and Japan’s, first vineyard-style hall.

Conservative Japanese audiences were quick to complain. A hall layout where neither the listener nor the musician has any place to hide visually or audibly was a bit too in your face. But Suntory had the blessing of the conductor the Japanese most admired. The Berlin Philharmonic’s music director, Herbert von Karajan, had overseen the construction of his own early vineyard-style concert hall, the celebrated 1963 Philharmonie.

Tokyo was already Asia’s classical music capital, with a couple of decent and not-so-decent halls, but music felt newly alive in Suntory. Once the hall began presenting all the great names and ensembles in classical music — more year in and year out than any other venue, Carnegie Hall included — greater Tokyo couldn’t help but notice. Over the next two decades, dozens of concert halls, big and small, were built throughout the country, many driven by Toyota.

These days, the shiny new halls in America and Europe, beginning with what may still be Toyota’s greatest masterpiece, the vineyard-style Walt Disney Concert Hall, get the attention. Toyota’s first Berlin venue, the Frank Gehry-designed Pierre Boulez Saal, is debuting. In California, we boast Toyota acoustics in, along with Disney and REDCAT, four outstanding college concert halls (at Stanford, USC, Chapman in Orange and Soka in Aliso Viejo).

Over the last year, I’ve visited several of Toyota’s halls in Japan to sense the effect they’ve had on the musical and, perhaps, civic life of their communities.

Suntory, which has just closed for maintenance after celebrating its 30th anniversary season, remains far and away the most prestigious concert address in the East, no matter the architecturally stunning opera houses and concert halls popping up in China, Indonesia, the Emirates and the Southern Caucasus.

Although Suntory may not have all the sophistication of Toyota’s latest designs, its sound remains engagingly immediate. The Vienna Philharmonic, an annual visitor that helped lead off the anniversary celebrations in the fall, sounds remarkably comfortable here despite the radical difference between modern Suntory and the orchestra’s heavenly 19th century home, the Musikverein.

Zubin Mehta conducted standard repertory, not always with a lot of spunk. A downside to Suntory’s prominence is that famous orchestras, knowing the Japanese reverence for tradition, too easily get away with the same old, same old.

Mehta did not push the Viennese, and Mozart and Brahms succumbed to blandness. But an opulent Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony and a sometimes radiant Beethoven’s Ninth felt, in this environment, as Viennese as a Sacher torte rushed overnight to Tokyo.

The dozen professional orchestras in the greater Tokyo area don’t have quite so much to thank Suntory for, what with the world’s great orchestras coming to town on a regular basis and playing in the city’s best space. Neither the New York Philharmonic nor the London orchestras have this much competition.

Yet when some of these Tokyo orchestras repeat their most important concerts in Suntory, their stature grows. I’m not sure why anyone would want to hear Japan’s most stellar orchestra, the NHK, play in its home multipurpose barn if the program is to repeat in Suntory.

Most of Toyota’s best halls resemble Suntory, but Triphony Hall, in the Sumida section of Tokyo, is ideal for the connoisseur of fragile sounds. That surely accounts for the resident Japan Philharmonic’s ability to play so quietly that, yes, you can imagine hearing a pin drop. All Toyota halls train audiences as well as musicians, but the Triphony regulars are special, even for Japanese devotees.

Still, a great hall remains but a tool and ultimately is only as good as its management. The same can be true of orchestras. The acoustical designs for Sapporo’s Kitara hall, now turning 20, were made around the same time Toyota was working on Disney, and there is a certain similarity to the sound. But the Sapporo Symphony has little to show for its two decades in Kitara, likely due to a lack of hall access for rehearsal and a management fondness for tired European conductors with a penchant for phoning it in.

The opposite tale is told in the ancient capital, Kyoto. Its seductively elegant hall by Arata Isozaki, the architect of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, is hidden away like one of Kyoto’s incomparable temples, which it in some ways resembles.

When the hall opened in 1995, the Kyoto Symphony was not up to the challenge of performing Mahler’s gargantuan Eighth Symphony, and the venue was deemed a failure. In fact, it is anything but. It’s my second favorite Toyota hall after Disney. The combination of an immaculate acoustic in a Zen-like environment requires unpretentious refinement, and that is what the Kyoto Symphony has now begun to acquire.

It so happens that the Kyoto Symphony will try again with Mahler’s Eighth on March 27. A month later, former L.A. Opera Music Director Kent Nagano will lead the Eighth with his Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra in Toyota’s hall. There is little to worry about anymore.

ALSO

L.A. Phil’s 2017-18 season will build bridges, Dudamel says

Race, justice and ‘Unchained’: L.A. Phil premieres work by James Matheson

The opera about Billie Jean King’s ‘Battle of the Sexes’

L.A. Opera’s 30-year-old ‘Salome’ is back, and not a kid anymore

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.