Alan Hergott and Curt Shepard donate 22 key works to MOCA exploring gender and queer identity

Los Angeles art collectors Alan Hergott and Curt Shepard began acquiring works as a couple in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, homing their sights on works that dealt with gender and queer identity.

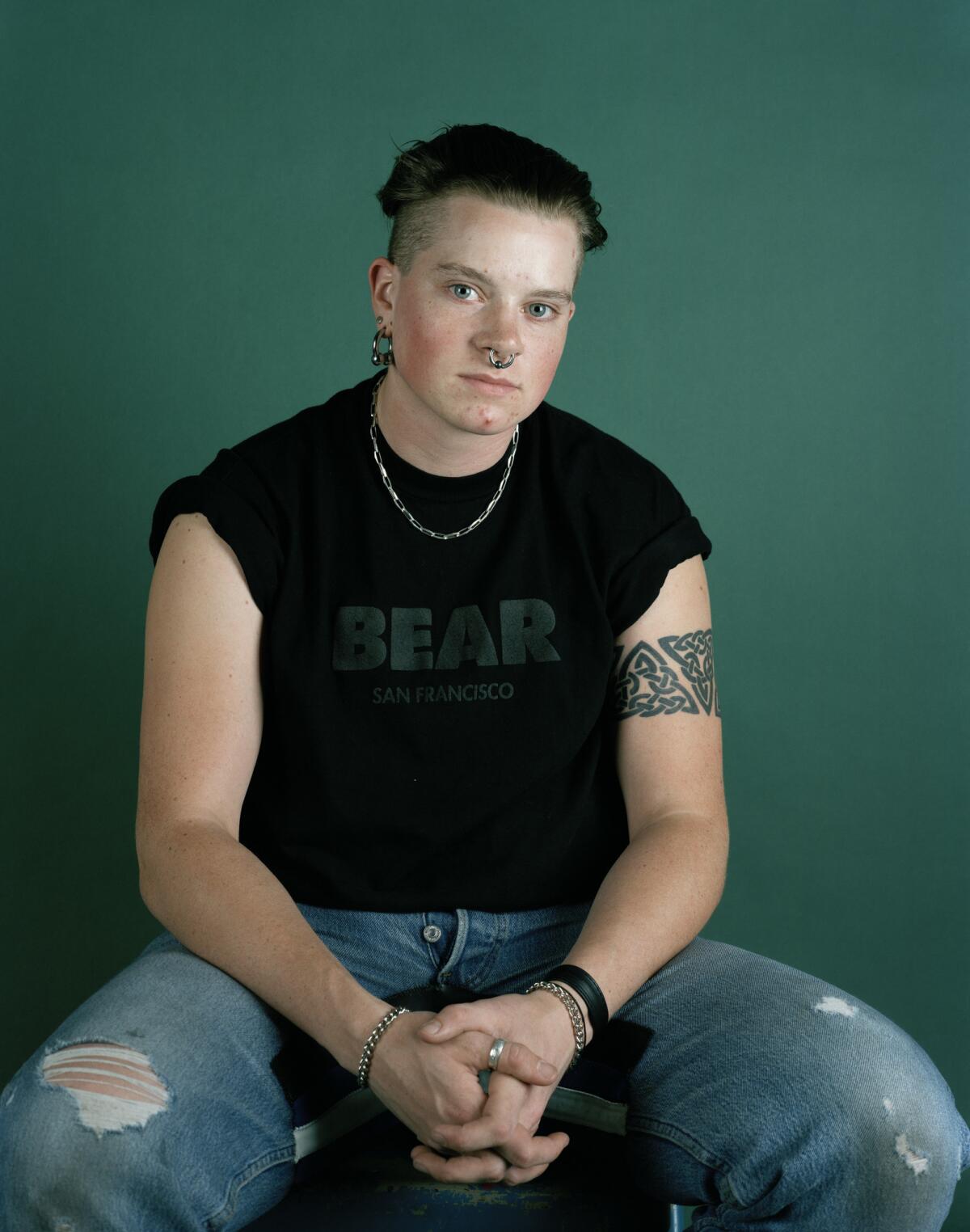

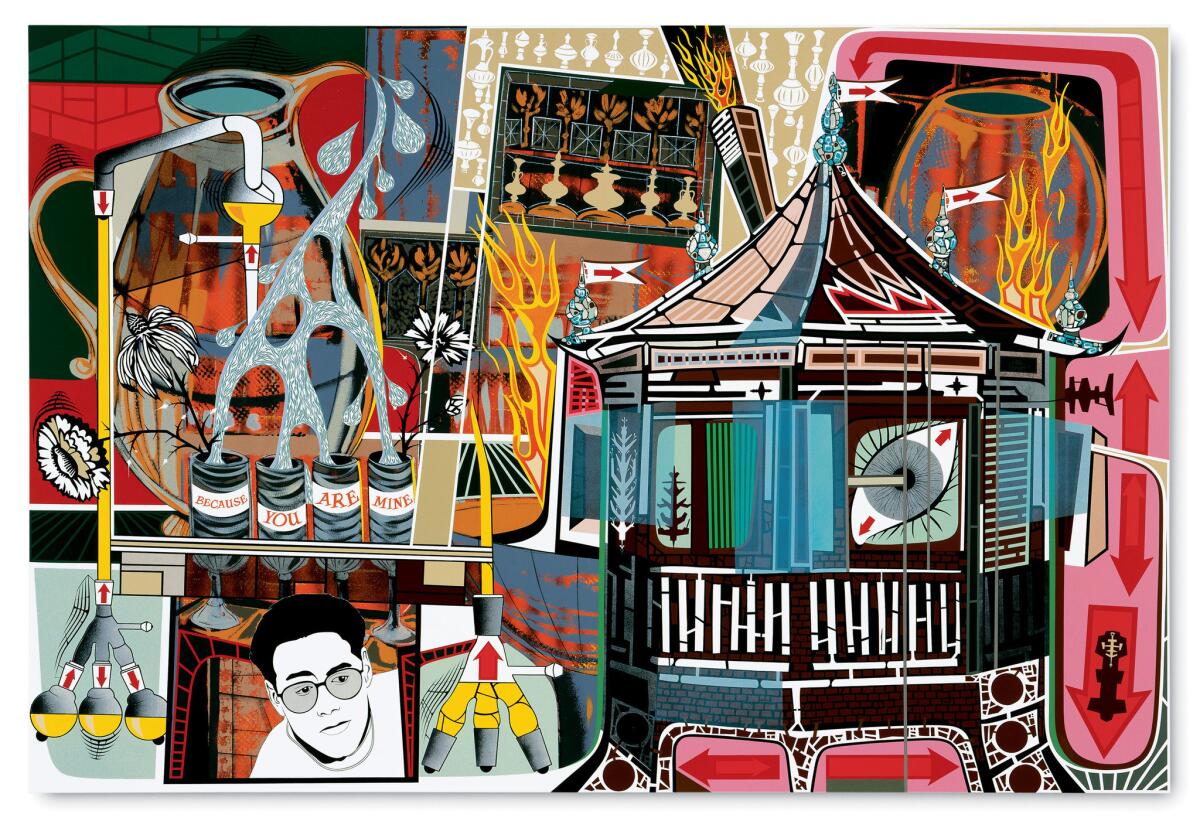

That meant acquiring photographs by Catherine Opie, whose visceral portraits explore questions of sexuality, or by the British duo Gilbert & George, known for creating brightly patterned, graphic works that naughtily fuse pop, religious iconography and homoeroticism.

Today, these artists and their works are part of mainstream discussions about art and its history. But in the early ’90s, Hergott and Shepard’s focus on gender and identity was often dismissed in art circles.

“Too niche, too gay, too twee, too tritely sexualized,” recalls Hergott of some of the reactions they received. “There was a lot of critical opinion that art and politics were strange, if not inappropriate bedfellows.”

A lot has changed.

Over the nearly three decades that the two have been together, Hergott, a prominent Beverly Hills entertainment lawyer who serves on the acquisitions committee of Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art, and Shepard, who serves as chief of staff at the Hammer Museum, have built a significant collection of some 200-plus paintings, photographs, sculptures and installations that explore one of the burning issues of our age.

There is a quiet subversion in the way that they collect, and in the way they want their collection and their identity to be perceived.

—

MOCA director Philippe Vergne

“Alan — and then Alan and Curt together — were prescient in recognizing the importance of thinking about masculinity and alternative sexualities in the 1980s, well before the reemergence of the term ‘queer,’” says Richard Meyer, an art historian who teaches at

Now Hergott and Shepard are donating a sizable portion of their groundbreaking collection, 22 pieces — including works by Opie and Gilbert & George — to the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. It’s the single biggest donation of art to MOCA since retired television executive E. Blake Byrne donated 123 works in 2004.

This donation comes on top of 18 other works that the couple have given to the museum over the years — high-profile pieces by key 20th century artists, including installationist Mike Kelley, painter Lari Pittman, photographers Andres Serrano and Hiroshi Sugimoto and the prominent conceptualists John Baldessari and Bruce Nauman.

“We’ve told dealers and artists for years that our entire goal was to be able to give it away to a museum or museums,” says Hergott.

Shepard says the gift was motivated by a desire to support an important Los Angeles museum in its mission. “I think this is a demonstration of a kind of commitment,” he says. “It’s making a statement about the importance of supporting public institutions.”

It’s a statement MOCA director Philippe Vergne is happy to hear.

“For me, the gift is important on so many different levels,” he says. “Even before talking about the collection itself, it’s the impact the gift will have. I see art patrons who have been deeply involved in the art community here and and internationally and are showing their trust in MOCA.”

And it comes at an important moment for the museum, which is righting itself after the troubled tenures of Jeremy Strick and Jeffrey Deitch.

More significant is the nature of the works being donated.

“They were extremely deliberate to pick and choose works that would complement what MOCA already has,” explains Vergne, “or in some cases it’s given MOCA access to work that we couldn’t access for financial reasons.”

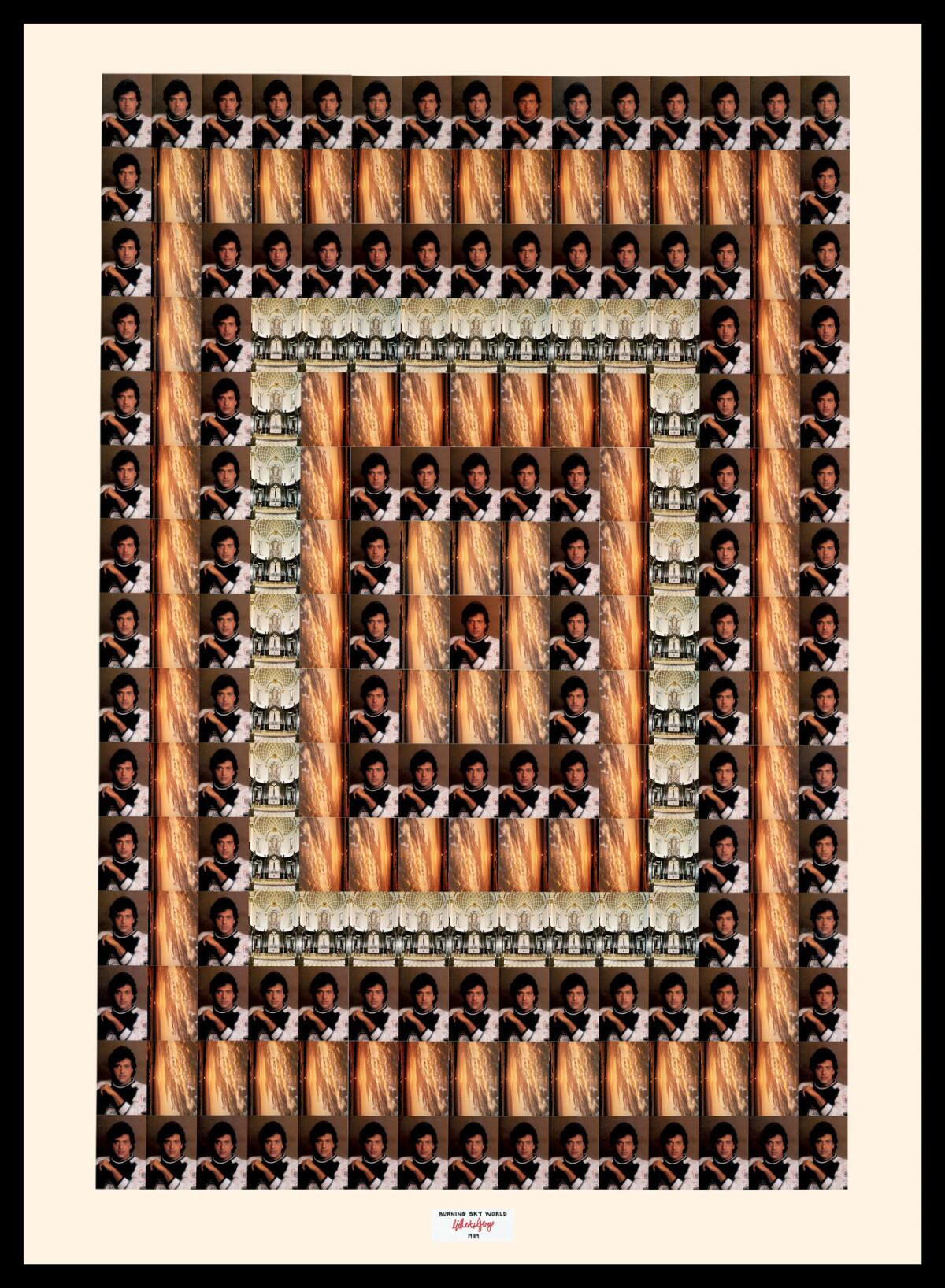

He cites the 1989 piece “Burning Sky World” by Gilbert & George, a photographic collage that checks in at a height of nearly 8 feet, and features a repeating pattern of a man, a sunset and a church interior, in a way that evokes stained glass. The artists have been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions such as the Tate Modern in London and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

“These works are likely not on the market,” says Vergne, “and certainly not in our market.”

For the couple, collecting has been a deeply rooted passion.

Hergott, who hails from Chicago, has a long-running interest in the arts. He studied theater as an undergraduate at the

He began to acquire his first works in the 1970s — shortly after arriving in L.A. (He came for a $10-an-hour clerking position at a firm that now bears his name: Bloom Hergott Diemer Rosenthal LaViolette Feldman Schenkman & Goodman.) His earliest purchase was a simple drawing acquired at a charity auction in Hollywood.

Shepard, who is originally from Oregon, also came to art early — on a junior-year-abroad program in Denmark when he was in college.

“My Danish dad was a patron at the Louisiana Museum and we had regular excursions there,” he recalls. “I saw my first Warhols, my first Giacomettis there. I came into a relationship with art there — I developed an eye, if not a schooled eye.”

They met in the late ’80s at a Los Angeles fundraiser for a gay and lesbian organization that provided social services to teens. Hergott was a patron of the organization. Shepard was wrapping up a Ph.D. in education at UCLA. “My plan was to go back up to the Pacific Northwest,” says Shepard with a wry chuckle. “But life intruded.”

The couple has now been together for 29 years.

From their earliest days, collecting was a mutual passion. And one of the earliest pieces they picked up as a couple was a painting by Richard Prince, “I Know This Guy,” from 1990. It is one of the artist’s early joke paintings, featuring a written gag alongside layers of images. The joke reads: “I met my first girl, her name was Sally. Was that a girl, was that a girl. That’s what people kept asking.”

“It appealed to us because it was snide and mean and crude about sexual identity,” Hergott says. “It’s very pointed and has meanings and resonances beyond the surface of the Borscht Belt audience reaction it might elicit.”

Too niche, too gay, too twee, too tritely sexualized. Critical opinion [said] that art and politics were strange, if not inappropriate bedfellows.

— Collector Alan Hergott

“We bought it from Stuart Regen,” says Shepard of the proprietor of the venerable Regen Projects — which is now run by Regen’s widow and business partner, Shaun Caley Regen. “It’s an early one that means the most to me. We’ve had it up quite a lot.”

The painting speaks to the nuanced ways in which Hergott and Shepard have approached collecting.

Early on, they were drawn to images that spoke to the idea of couples or pairs. They acquired a 1985 drawing by Nauman that features the outline of two nude male figures clasping hands. There is the 1990 diptych by John Baldessari that shows a pair of dwarfs facing off. In a 2002 painting by John Currin, titled “Two Guys,” a pair of rosy cheeked men pose in familial embrace — rendered in the fairytale color palette for which the painter is known.

Shepard says it was their experiences as a visible out gay couple in the ’80s and ’90s that inspired the interest.

“It was a big deal that we were a gay couple in Hollywood,” he says. “We went to many charity events the first number of years in our relationship. We were often the only openly gay couple in the room. And if there was a program, we were often the only gay couple listed. So, coupledom was something that we were conscious of — we gravitated early to things that involved couples.”

This translated broadly to works that featured pairings: Diptychs and installations that juxtaposed one image or object with another.

“It’s like we sought out works that spoke to each other literally and figuratively,” says Hergott.

Vergne says this makes the collection greater than just a simple gathering of didactic expositions on gayness.

“There is a quiet subversion in the way that they collect,” he says, “and in the way they want their collection and their identity to be perceived.”

Meyer concurs.

“What’s extraordinary about the collection,” he states via email, “is the range of artists — male and female, queer and straight — who take this issue in surprising ways.”

This might include a picture of a young man, looking battered after his turn in a bullfighting ring, by the Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra. Or a dreamy image of a boy climbing a tree by New York artist Collier Schorr. Both are works by prominent female photographers; both were part of the donation to MOCA.

These works, over the course of Hergott and Shepard’s romantic life, have circulated in and out of their home — a hilltop abode which looks over Beverly Hills, and was designed by the Los Angeles architect Michael Maltzan in the late 1990s. (On top of being important art patrons, the couple are important architectural patrons too. Their home, completed in 1998, was the first ground-up house designed by the award-winning architect.)

Over the years, they have been dedicated supporters of the Hammer Museum and MOCA, which has been an important source of inspiration.

“Some of the big pleasures of collecting has been in being connected with many of the artists,” says Shepard. “Some of the dealers around town are some of our best friends. The museum people are some of our very good friends. That is as important to me as the objects.”

And though they still buy art, the couple, these days is also very keen in giving it away.

“I jokingly tell people that the reason I’m still working is so that I can afford to give away the best of the art,” Hergott says with a laugh. “And not to put too fine a point on it, we’re not getting any younger. If we’re going to give works while we’re alive, we’re going to have to step it up a bit.”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO:

Painter Jonas Wood turns Arata Isozaki's MOCA exterior into building-sized art canvas

Review: R.H. Quaytman makes paintings as sculptures, mysterious and seductive at their best

How to remake the L.A. freeway for a new era? A daring proposal from architect Michael Maltzan

With pointed, political new work, Llyn Foulkes, 82, shows he's far from finished

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.