Reporting from Park City, Utah — On Friday, just a few hours before Donald Trump would announce an executive action banning many residents of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S., the filmmaker Evgeny Afineevsky was engaging in a different sort of governmental interaction.

Afineevsky was at a Salt Lake City science museum screening his new film, “Cries from Syria,” for Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams and other local officials. The film offers a detailed and devastating account of the civil war that has gripped the country for more than five years, and its director was on a mission — he wanted the images of brutality to serve as a wake-up call for supporters of exactly the kinds of policies undertaken by the new president.

FULL COVERAGE: Sundance Film Festival »

“As soon as it’s seen, it open minds and hearts — these are human beings that have families,” Afineevsky said in an interview. “This movie can be a tool in helping people understand.” McAdams, a Democrat, later said his jurisdiction would not enforce Trump’s ban.

You can talk to a lot of artists about repression. Few have the experience that Afineevsky does.

The 44-year-old filmmaker, who now makes his home in Los Angeles, was born in the U.S.S.R. circa 1972. He spent the first 18 years of his life under Soviet rule, in the Muslim-majority republic of Tatarstan. He left because he felt he couldn’t express himself artistically in his home country, emigrating first to Israel and then to the U.S., where he is now a citizen.

More recently, though, he’s been toiling much farther away: on the Turkey-Syria border, and sometimes in war-torn Syria itself, with the people who either can’t afford or can’t bring themselves to leave. He’s spent two years there investigating the Syrian civil war for his new movie, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last week ahead of its debut on HBO in March.

“People need to hear these stories. But the world is silent,” Afineevsky said, speaking in the incongruous precincts of this picturesque resort town.

1/77

Gael Garcia Bernal speaks during the 2017 Sundance Film Festival Awards at Basin Recreation Field House in Park City, Utah, on Saturday.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images) 2/77

Bryan Fogel, right, with cast and crew members, accepts the Orwell Award for his film “Icarus.”

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images) 3/77

Director Michael Larnell, right, and Sean Kirkland accept the US Dramatic, Breakthrough Performance award on behalf of Chante Adams for the film “Roxanne Roxanne.”

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images ) 4/77

Peter Dinklage presents the U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at Sundance.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 5/77

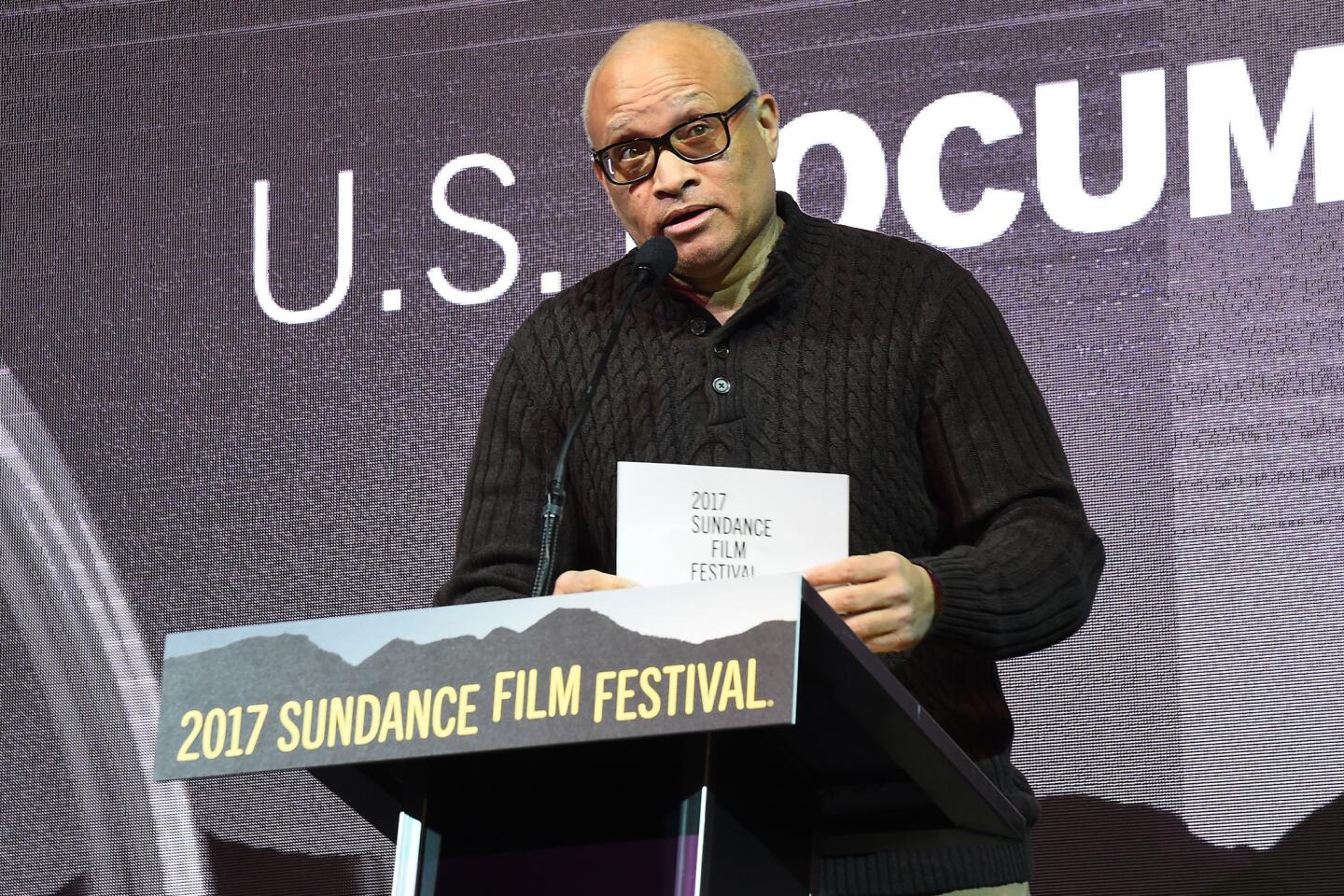

Larry Wilmore speaks during the 2017 Sundance Film Festival Awards ceremony.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 6/77

Actors Kevin Bacon, left, and Kathryn Hahn at the premiere of “I Love Dick” at the MARC Theatre.

(Arthur Mola / Invision / Associated Press) 7/77

Actor Peter Dinklage, left, and filmmaker Mark Palansky of “Rememory” attend The IMDb Studio featuring the Filmmaker Discovery Lounge.

(Rich Polk / Getty Images for IMDb) 8/77

Analeigh Tipton and Jason Schwartzman attend the Creators League Studio.

(Jonathan Leibson / Getty Images for Creators League) 9/77

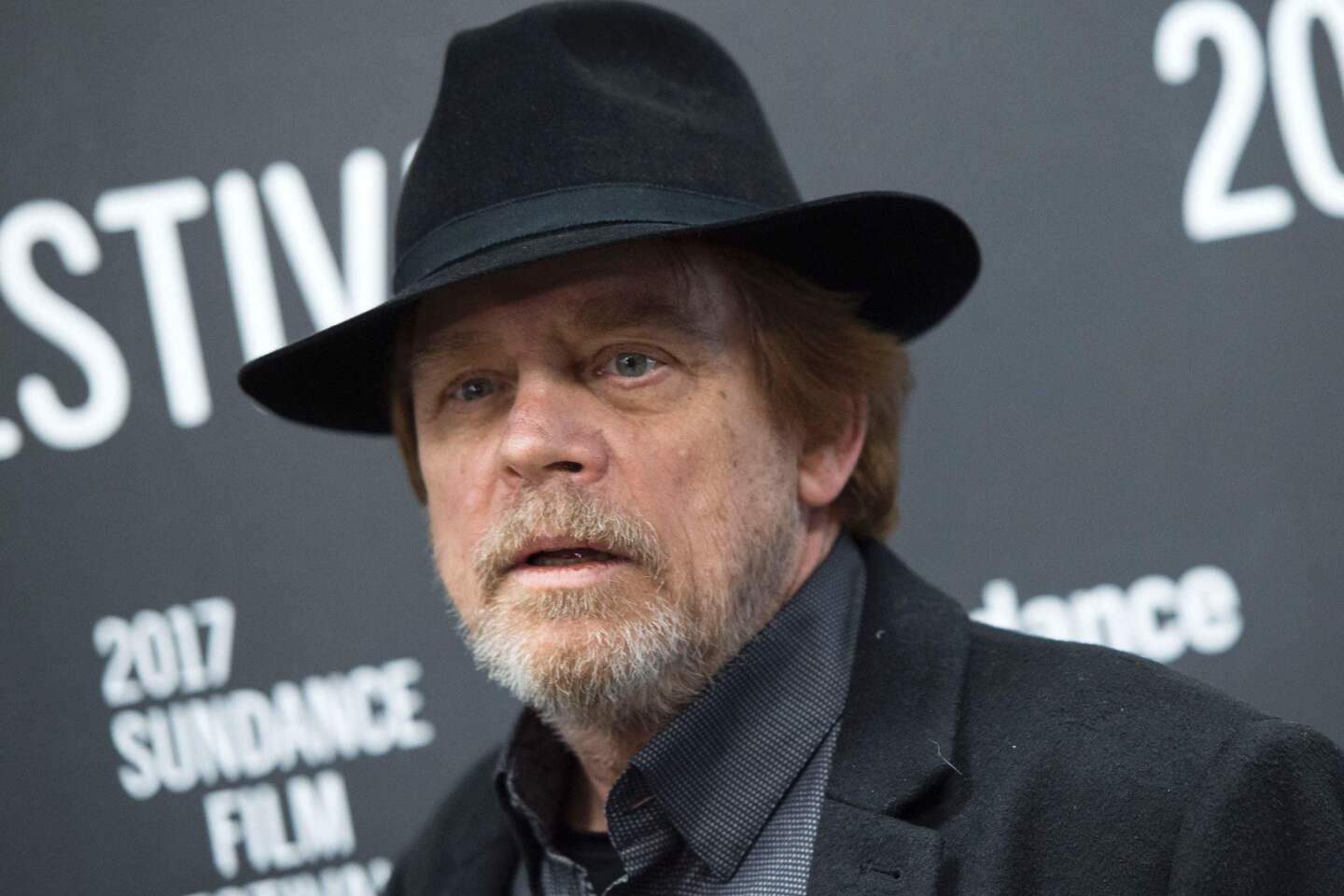

Actor Mark Hamill attends the “Brigsby Bear” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre.

(Valerie Macon / AFP/Getty Images) 10/77

Actors Anne Heche, Thomas Sadoski and AnnJewel Lee Dixon of “The Last Word” attend The IMDb Studio featuring the Filmmaker Discovery Lounge.

(Rich Polk / Getty Images for IMDb) 11/77

Actors Zoey Deutch and Nicholas Hoult, director Danny Strong of “Rebel in the Rye” and Kevin Smith, top, attend the IMDb Studio featuring the Filmmaker Discovery Lounge.

(Rich Polk / Getty Images ) 12/77

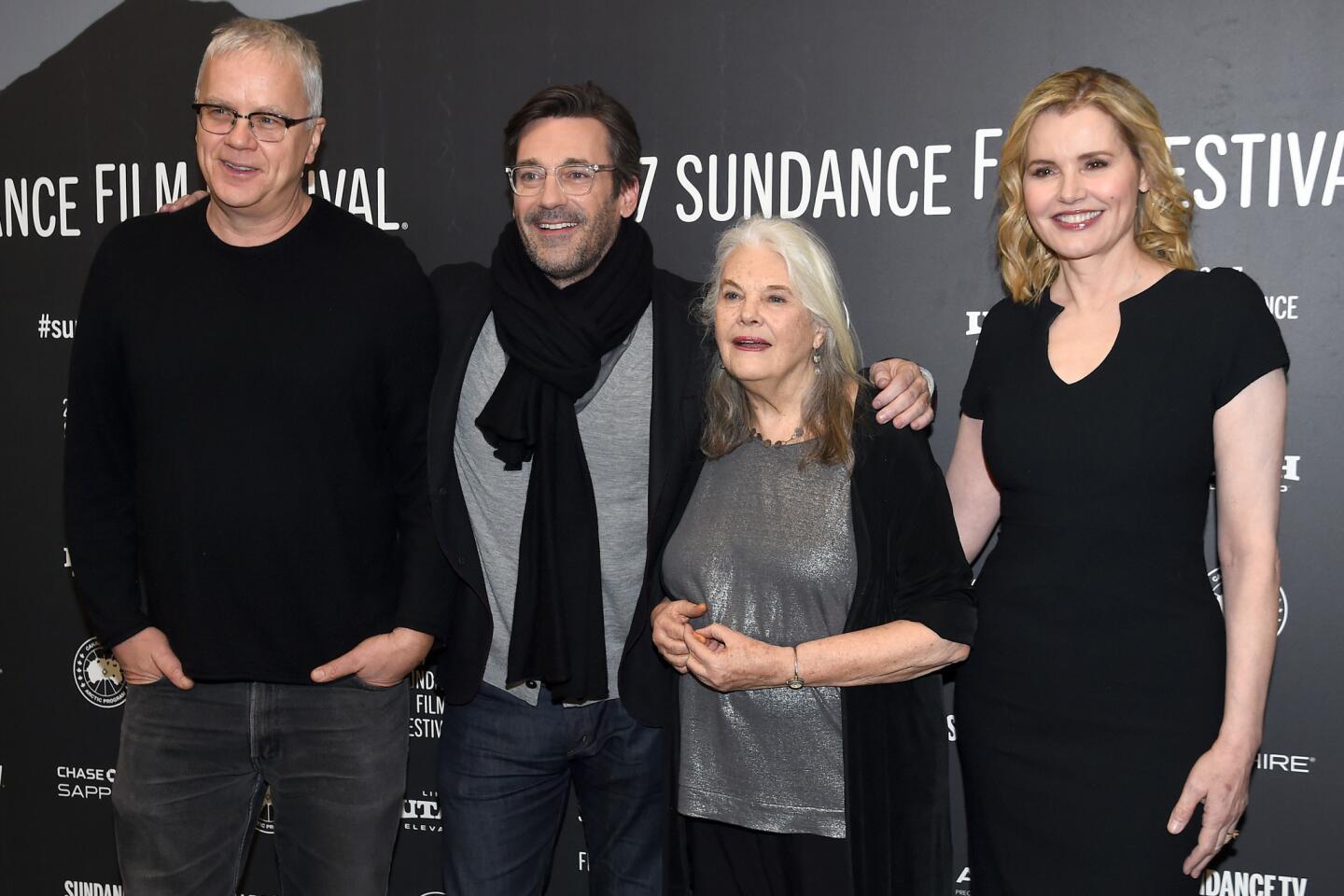

Actors Tim Robbins, Jon Hamm, Lois Smith and Geena Davis attend the “Marjorie Prime” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 13/77

Brigsby Bear attends the “Brigsby Bear” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 14/77

Actor Lakeith Stanfield, left, and the film subject he plays, Colin Warner, attend the “Crown Heights” premiere at Library Center Theater.

(Sonia Recchia / Getty Images) 15/77

Actor Nicholas Hoult at the premiere of “Rebel In The Rye.”

(Danny Moloshok / Invision / Associated Press) 16/77

Comedian Patton Oswalt speaks onstage at the Shorts Program Awards and party at Jupiter Bowl.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 17/77

Times reporter Amy Kaufman and Logan Lerman speak at the Cinema Cafe at Filmmaker Lodge.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 18/77

Actress Ann’Jewel Lee attends the “The Last Word” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre.

(Alberto E. Rodriguez / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 19/77

Executive producer Harvey Weinstein and executive producer and rapper Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter attend the “Time: The Kalief Browder Story” Sundance world premiere at The Marc Theatre.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images for Spike TV) 20/77

Actress Sanaa Lathan attends the “Shots Fired” premiere.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 21/77

Marti Noxon attends the Feature Fillm Competition dinner.

(Alberto E. Rodriguez / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 22/77

Director Mark Palansky, actor Martin Donovan, actress Katheryn Kirkpatrick, Matt Ellis, actress Julia Ormond and actor Peter Dinklage attend the “Rememory” premiere.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 23/77

Actors Logan Lerman, Blake Jenner, Elle Fanning, Michelle Monaghan and Margaret Qualley attend the “Sidney Hall” party at the Acura Studio at Sundance Film Festival 2017.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images for Acura) 24/77

Cast and crew speak onstage during the “Shots Fired” premiere.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 25/77

Actress Chloe Sevigny at the premiere of the film “Beatriz at Dinner” at the Eccles Theatre.

(Arthur Mola / Invision/Associated Press) 26/77

Chef Cat Cora prepares entrees during a luncheon hosted by Glamour editor Cindi Leive and photographer Amanda de Cadenet.

(Vivien Killilea / Getty Images) 27/77

Actresses Alfre Woodard and Elle Fanning attend the Lunch Celebrating Films Powered by Women.

(Vivien Killilea / Getty Images for Glamour) 28/77

Jon Hamm, left, and Tim Robbins of the “Indiewire in Conversation” panel.

(Jack Dempsey / Invision / Associated Press) 29/77

Shirley MacLaine, left, Salma Hayek, Cindi Leive, and Dee Rees at the Lunch Celebrating Films Powered by Women event.

(Vivien Killilea / Getty Images for Glamour) 30/77

Reginald Hudlin, left, Stephanie Allain, Gerard McMurray, Mel Jones and Jason Michael Berman at the premiere of director McMurray’s “Burning Sands.”

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images ) 31/77

Malia Obama strolls on Main Street at the Sundance Film Festival at Park City, Utah.

(Danny Moloshok / Invision / Associated Press) 32/77

Producer Noshre Chkhaidze, left, director Simon Grob, actress Ia Shugliashvili and producer Jonas Katzenstein attend the “My Happy Family” premiere at Egyptian Theatre.

(Alberto E. Rodriguez / Getty Images) 33/77

Viewers take in Al Gore’s film “Melting Ice” on Condition One’s virtual-reality system at the Sundance VR release party.

(Valerie Macon / AFP/Getty Images) 34/77

IMDb founder and Chief Executive Col Needham enjoys his 50th birthday party.

(Rich Polk / Getty Images ) 35/77

Actress Connie Britton attends the “Beatriz at Dinner” premiere at Eccles Theatre.

(Valerie Macon / AFP/Getty Images) 36/77

Marti Noxon, left, writer and director of “To the Bone,” poses with cast members Lily Collins, center, and Carrie Preston at the Jan. 22 premiere of the film in Park City Utah, during the 2017 Sundance Film Festival.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision /Associated Press) 37/77

Cartoonist Daniel Clowes, the screenwriter of “Wilson,” poses at the Jan. 22 premiere of the film in Park City, Utah, during the Sundance Film Festival.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 38/77

Chanté Adams, Roxanne Shanté and actress Nia Long pose at the Jan. 22 premiere of the film “Roxanne Roxanne” in Park City, Utah, during the Sundance Film Festival.

(Arthur Mola / Invision / Associated Press) 39/77

From left, Jeff Skoll, Al Gore, Heather Rae and David Suzuki speak on stage Jan. 22 at the New Climate Lunch Roundtable during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images ) 40/77

David Suzuki speaks on stage Jan. 22 at the New Climate Lunch Roundtable during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 41/77

“Strong Island” executive producer Danny Glover relaxes Jan. 22 at the Indiewire Photo Studio at Chase Sapphire on Main during Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Jack Dempsey / Invision / Associated Press) 42/77

Actress Brittany Snow of “Bushwick” attends the Acura Studio on Jan. 22 during Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images ) 43/77

DJ Cool V and Biz Markie attend the Acura Studio Jan. 22 during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images) 44/77

Luca Guadagnino, Timothee Chalamet, Armie Hammer, Michael Stuhlbarg and Walter Fasano attend the Jan. 22 “Call Me By Your Name” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images ) 45/77

Roxanne Shante performs onstage at the Jan. 22 “Roxanne, Roxanne” party in the Acura Festival Village during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images ) 46/77

Biz Markie performs onstage at the Jan. 22 “Roxanne, Roxanne” party in the Acura Festival Village during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images ) 47/77

Michaela Watkins, Jill Soloway, Jessica Williams and Stacey Wilson Hunt speak onstage Jan. 22 at an event hosted by the Bentonville Film Festival during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Joe Scarnici / Getty Images) 48/77

Roxanne Shante and Chante Adams attend the Jan. 22 “Roxanne, Roxanne” party during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images ) 49/77

Jon Daly, Brett Gelman, Nia Long, Judy Greer, Janicza Bravo and Shiri Appleby attend the Jan. 22 “Lemon” premiere at Library Center Theater during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 50/77

Jack Black attends the Jan. 22 premiere of “The Polka King” at the Eccles Center Theatre during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images ) 51/77

Willie Garson, Jason Schwartzman, Jack Black, Jacki Weaver and Jenny Slate pose at the Jan. 22 premiere of “The Polka King” during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(Danny Moloshok / Invision / Associated Press) 52/77

Tim Robbins, center, shakes hands with Mary J. Blige, left, while introducing Blige to his son, Jack Robbins, at Sundance at the Music Lodge during the Sundance Film Festival.

(Jud Burkett / Invision for The Music Lodge) 53/77

Actresses Elizabeth Olsen, left, and Aubrey Plaza from “Ingrid Goes West” during the “Indiewire in Conversation” panel at Chase Sapphire on Main.

(Jack Dempsey / Invision for Chase Sapphire) 54/77

Executive producer John Legend poses at WGN America’s “Underground” Sundance red carpet screening.

(Danny Moloshok / Invision / Associated Press) 55/77

Actors Aldis Hodge, left, and Jurnee Smollett-Bell at WGN America’s “Underground” Sundance red carpet screening during the 2017 Sundance Film Festival.

(Danny Moloshok / Invision / Associated Press) 56/77

People march down Main Street during the March on Main event during the Sundance Film Festival.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times) 57/77

Brett Haley, left, director of “The Hero,” poses with cast members Nick Offerman, Sam Elliott and Katharine Ross at the premiere of the film at the Library Center Theatre.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 58/77

Laura Prepon, left, a cast member in “The Hero,” with her fiancé, actor Ben Foster, at the premiere of the film at the Library Center Theatre.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 59/77

Director Anthony Hemingway, left, producer John Legend, actors Jurnee Smollett-Bell and Aldis Hodge, and writer Misha Green speak at WGN America’s “Underground” panel at the Blackhouse Foundation.

(Gustavo Caballero / Getty Images for WGN AMERICA) 60/77

Jason Mitchell, left, Dee Rees, Rob Morgan, Carey Mulligan, Mary J. Blige and Garrett Hedlund attend the “Mudbound” premiere at Eccles Center Theatre.

(Valerie Macon / AFP/Getty Images) 61/77

Actors Lily Mojekwu, left, Griffin Dunne, Kathryn Hahn and Kevin Bacon of “I Love Dick” attend The IMDb Studio featuring the Filmmaker Discovery Lounge.

(Rich Polk / Getty Images for IMDb) 62/77

Harvey Weinstein attends the “Wind River” party at the Acura Studio at Sundance Film Festival.

(Neilson Barnard / Getty Images for Acura) 63/77

Actress Brittany Snow attends the “Bushwick” premiere.

(Alberto E. Rodriguez / Getty Images) 64/77

A policeman with a bomb sniffing dog checks out a snow pile next to a Banksy artwork along Old Main Street on the first day of the 2017 Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(George Frey / EPA) 65/77

Omar Wasow, left, an assistant professor at Princeton in the department of politics, and director Jennifer Brea attend An Artist at the Table benefit during the 2017 Sundance Film Festival at DeJoria Center in Kamas, Utah.

(Nicholas Hunt / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 66/77

Former Vice President and cast member Al Gore speaks as he arrives for the premiere of “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power” at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(George Frey / EPA) 67/77

Kristen Stewart, left, David Shapiro, Josh Kaye and Sydney Lopez attend the world premiere of director Kristen Stewart’s “Come Swim” at Prospector Square Theatre.

(Joe Scarnici / Getty Images for Refinery29) 68/77

Kristen Stewart attends the world premiere of “Come Swim.”

(Joe Scarnici / Getty Images for Refinery29) 69/77

Actresses Molly Shannon, Alison Brie, Kate Micucci, and Aubrey Plaza attend “The Little Hours” premiere at Library Center Theater.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 70/77

Jon Gabrus, Dave Franco, Nick Offerman, Trevor Groth, Aubrey Plaza, Jeff Baena, Molly Shannon, Alison Brie, Jemima Kirke, Kate Micucci, Adam Pally and Lauren Weedman, from left, attend “The Little Hours” premiere.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 71/77

Former Vice President and cast member Al Gore, left, and Director of the Sundance Film Festival John Cooper arrive for the premiere of “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power.”

(George Frey / EPA) 72/77

Actors Nick Offerman, left, Molly Shannon, and Dave Franco attend “The Little Hours” premiere.

(Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival) 73/77

Executive director of the Sundance Institute Keri Putnman, left, founder and president of the Sundance Film Festival Robert Redford and director of the Sundance Film Festival John Cooper talk to the media to open the 2017 Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

(George Frey / EPA) 74/77

Robert Redford, founder of the Sundance Institute, addresses the audience at the opening night premiere of the film “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power,” at the Eccles Theater.

(Chris Pizzello / Invision / Associated Press) 75/77

People are bundled up as temperatures dropped below 20 degrees along Main Street in Park City, Utah, as the start of the Sundance Film Festival approached.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 76/77

A trolley rolls up Main Street in Park City, Utah, as the Sundance Film Festival approached.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 77/77

The Egyptian Theatre on Main Street, one of the major venues for the Sundance Film Festival, is lit up a few nights before the festival’s opening in Park City, Utah.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) “The obligation is for filmmakers to take the accounts of those no longer with us and bring them to people. It’s depressing to read the news,” he added. “Nobody wants to educate themselves. I want to tell a comprehensive story the audience needs to hear.”

Afineevsky is certainly well-positioned to convey what’s happening in the most volatile — and, as the events of the last few days make clear, sometimes most misunderstood — country in the Middle East. At a time when many in Hollywood are countering the Trump ban with statements and speeches—witness the comments at the SAG Awards by actors from “Stranger Things,” “Moonlight” and “Hidden Figures” Sunday night—his movie offers a more tangible response. There is value in public pronouncements, which can elicit hot and even necessary reactions on social media. But with his new work, the Russian-American director proves that the most enduring way for entertainers to challenge undesirable policies is to make art about it.

“Cries from Syria” shows, via both direct interviews with a range of Syrian people and voluminous images from citizen journalists, the ordinary folks caught in the war between Bashar Assad’s military, the Free Syrian Army, the Syrian Democratic Forces and various jihadi groups — a conflict that has claimed as many as 470,000 lives and still rages on.

Screening for the first time just days before Trump’s executive action, the film serves as a kind of humanist response to the president’s ban. To those who say such measures are needed to stop terrorism, the film powerfully and often graphically shows what many of these so-called threats are: victims themselves.

In one scene, a father is seen trying to save his children on a rickety boat in the Mediterranean as, one by one, they slip through his hands and drown.

In another, a school is under an aerial attack — a tragedy remembered only because a young boy and his cousin were allowed to leave after sitting more quietly than anyone in the class. By the time they arrive home, the entire school has been razed by a missile, scores of their classmates killed.

In perhaps the most horrific scene, dozens of children are killed in a chemical raid by Assad’s army — an event portrayed with startling explicitness.

Afineevsky, who documented the 2014 Ukrainian revolution from the ground in his previous film, “Winter On Fire” (it was nominated for the documentary Oscar), has again gone deep to show a side of a conflict most mainstream journalism institutions lack either the resources or fortitude to chronicle.

“Cries from Syria” is thus more than a journalistic snapshot; it’s a definitive document of one of the most bloody of modern conflicts. What it lacks in easy digestibility — images such as the gassing make this one of the most difficult documentaries to watch in recent memory — it compensates for with historical importance. When, years from now, in a bid to understand or administer self-blame, the world looks back at the Syrian civil war, it’s movies like this that will pinpoint most clearly what happened, told by the people to whom it was happening.

“People say, ‘Why did you show so much?’” Afineevsky said, referencing some murmurs at the festival that the film can be hard to watch, in particular because of all the images of children. “But you have to show it to understand what happened. Otherwise it’s just an abstraction, something on the news.”

Viewers might be moved by the stories of many of the adults too. Among the most powerful is Kholoud Helmi, a resident of Darayya, a suburb of Damascus. Helmi talks movingly, in fluent English, about the suffering she witnesses and the changes she’d like to see.

Even less personal moments land with a visceral power: as an animated map indicating where chemical weapons have fallen begins to unnervingly fill up, for instance, as an unseen man sings plaintively, driving home the tragedy.

And if the film is often told from the perspective of supporters of the Free Syrian Army — they comprise many of the interviews — it also is interested in victims far more than fighters. When children make up a disproportionate amount of the film, thoughts about politics can fall away; among the many haunting images is a young boy nonchalantly drawing a picture of the various armies closing in around his town the way most children crayon their handprint or the family pet.

(Two other movies about the region, “City of Ghosts” and “Last Men in Aleppo,” also premiered at Sundance, completing a kind of trilogy of war horror. The former, about citizen journalists behind the groundbreaking Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently Facebook page comes from a different Oscar nominee, “Cartel Land” director Matthew Heineman; encountering the heroic subjects at a festival party was one of the most chilling-but-inspiring experiences this reporter has ever had at Sundance. The latter, meanwhile, takes a more focused look at the White Helmets, the war’s bold rescue group, and won a documentary prize Saturday night.)

The message of Syria movies should not be limited to far-flung places, Afineevsky said.

“These people start with a dream they’ve never had, of democracy. They’ve never had free speech,” said the director, who with a thick beard, tousled salt and pepper hair and intense way of speaking projects a moral seriousness above his outgoing demeanor. “And we have all of that in the U.S. But we should cherish it. There were states last week that wanted to ban protests. The idea that this could only happen in a place like Syria is not true,” he added. “I want people in America to see this movie and appreciate what we have. We have to cherish it so we can fight for what we have.”

Afineevsky hopes to show “Cries from Syria” to wide swaths of this nation’s capital, including to members of the Trump administration, before its cable debut.

He says he strongly opposes Trump’s executive action restricting entry from countries including Syria, not only on humanitarian grounds but pragmatic ones. “Trump is making a mistake if he thinks closing the border will prevent things. At the end of the day we’re talking about a lot of kids. And if we don’t help them and provide shelter, [Islamic State] will be their only shelter.”

He noted that Syrians make up barely a quarter of the refugees that come to the U.S., and also noted that this was the wrong way to neutralize a threat for other reasons.

“It’s not 20 or 30 years ago where you can shut doors and prevent terrorism,” he said. “It doesn’t work that way. There are people who live here who follow [Islamic State’s] ideology. It has very little to do with Syrians. Syrians are the ones suffering the most from terrorism.”

But he also retains optimism that the White House will see his film and keep an open mind.

“I’m targeting everybody,” he said. “Almost every senator has kids or grandkids. Same with Donald Trump — he has a wife and kids and grandkids. Mike Pence has a wife and kids. We need to remind them all these people [caught in the Syrian civil war] have wives or kids, or are wives and kids.”

For the moment, one can be forgiven for seeing reasons to lose hope. Helmi had come to the U.S. to promote the movie at Sundance. She made appearances at screenings, speaking to audiences eager to hear her story firsthand. She set out on Wednesday to return to her temporary home on the Turkish side of the Turkish-Syria border, where she has lived since fleeing Darayya. When she boarded a plane at Salt Lake City International Airport, Helmi believed she’d be returning to the U.S. in about eight weeks for the next round of publicity, including the HBO premiere. The ban has now thrown that into doubt.

“There are a lot of questions right now. Will she be able to travel to our country? Will she be able to talk about this important story?” Afineevsky said.

Asked about her state of mind, the director pulled no punches.

“She was devastated,” he said, noting he had spoken to her this past weekend after the ban was announced. “This movie was hope for her, hope for a lot of families that were coming to Utah.” (The state has been hospitable to refugees, with an estimated 60,000 from Syria and elsewhere currently living here.)

But Afineevsky said he refuses to give in. “It’s a dream slowly. These people have hope, I still have hope. We want to be able to change something in our country too.”

Late in his movie, that central tension — between optimism and despair, belief and doubt — is given expression by several subjects. Besieged by years of death and displacement, one shaken Syrian civilian says, “I cannot imagine how a person does this to another person,” adding, “For Syrians I think it becomes normal. It will never be normal but it becomes like daily things you see.”

Another is more bright-eyed. “We want to see a more beautiful Syria so we are working on rebuilding it. Our big dream is to see our country more beautiful. Our dream is to end this war.”

But hovering over them are more grim realities. As one person talks about using music to ease the pain, another offers a tart response. “With such brutality,” they say, “it is not enough just to sing.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

steve.zeitchik@latimes.com

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT