Desperation is driving an indigenous tribe in Venezuela to make the trek into Brazil

Bergassio Quiñonez knew he had to get his family out of Venezuela when his wife and two young daughters went without eating for four days.

Their home in Mariusa National Park, where Quiñonez and his family lived with about 600 other indigenous Warao people, was quickly becoming uninhabitable. Salt water was moving farther up the Orinoco River during the dry season, killing the freshwater fish they ate, and Venezuela’s political and economic crisis meant that store-bought food was also becoming scarce.

“Even if there was food on the shelves, nobody could afford it,” said Quiñonez, a teacher of the Warao language and culture, sitting with his legs crossed on a single, uncovered mattress in the corner of a room his family now shares with several other Warao from the same village.

He ran through the math: He earned the equivalent of $20 a month. A bag of rice was $7 and a bag of sugar was $12.50. “Then the water became salty and left us with no fish. Our children could only drink water when it rained,” he said.

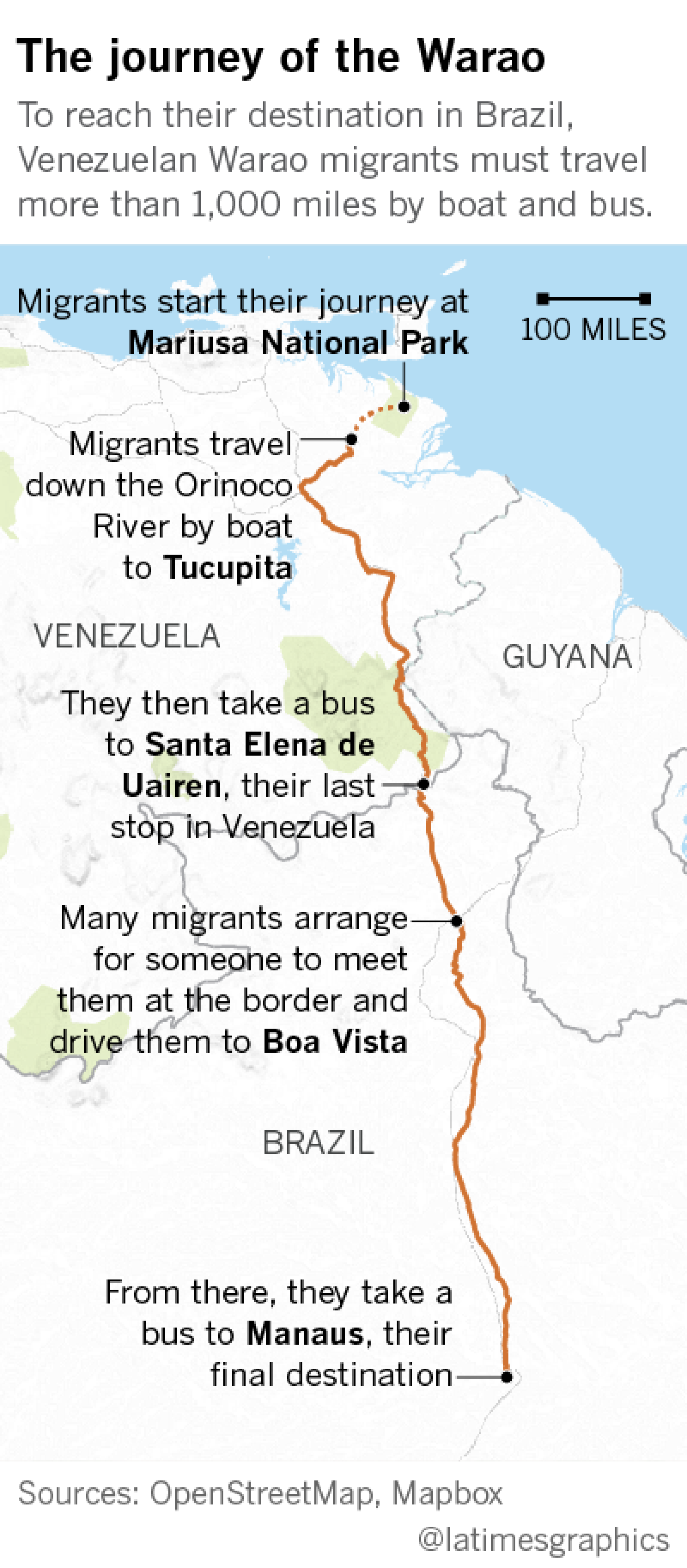

So Quiñonez and his family joined an exodus of more than 400 Warao who left their homes in northeastern Venezuela beginning in December to make the long, arduous journey to Brazil to settle in the Amazonian capital of Manaus.

The Warao are among tens of thousands of Venezuelans who have fled the violence and hunger that have subsumed their country under the unpopular president,

The Warao are one of the region’s oldest indigenous groups, with most of their total population of 20,000 living in Venezuela, while other, smaller groups have settled in neighboring Guyana and Suriname. The word Warao translates to "boat people," a reference to their historical connection to the water, in particular the Orinoco River. They have deep roots in the swamplands where the Orinoco drains into the Atlantic Ocean; now they are abandoning it in order to survive.

More Warao are arriving in Manaus every day, pushing the number of those settling in the city steadily higher. Although the trip is expensive and long for the Warao — it can take multiple boat and bus rides and several weeks to reach the Brazilian city — those who have made the journey say it was worth it just to see their children eat.

Quiñonez and his family left Mariusa in January and descended the Orinoco by boat for one week before arriving in Tucupita, the hot and humid capital of Venezuela’s Delta Amacuro state. His mother had already gone ahead with a previous group of Warao in an attempt to find food, and he heard by word of mouth that she had arrived in Brazil.

In Tucupita, Quiñonez, his wife and their two daughters slept on the streets for a week while attempting to sell a freezer his mother had left behind so her son could pay for his family’s bus tickets to Santa Elena de Uairen, a town that borders the northern Brazilian state of Roraima.

Once in Santa Elena, they built a makeshift shelter under a tree, where they lived for one month while Quiñonez worked as a shoe shiner in order to buy chicken and flour to feed his family, and to save enough money to cross the border and get to Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima. Because the children had no ID, they decided not to risk the usual border crossing, instead taking a long detour on foot and in the rain to avoid the Brazilian federal police. After making it across the border, they paid the equivalent of $46 to be driven 3 ½ hours to Boa Vista.

During the month he and his family spent there before moving on to Manaus, where they heard conditions were better, Quiñonez returned to Tucupita to collect more artisanal products to sell — hammocks, woven hats, bows and arrows. He also picked up ticks, which he ended up passing to the other members of his family and have left him scarred across his shoulder and chest.

As arduous as the journey is, Quiñonez and others say it’s worth it. Still, life in Brazil is far from easy.

Although they are happy to be in Manaus, where meals are regularly handed out by nongovernmental organizations, some are living under the sweltering sun and regular rain in a grassy area next to a bus terminal. Here, they have erected makeshift tents made from tarps and other leftover materials.

Others are housed in a cluster of grungy and stiflingly hot buildings in downtown Manaus that used to be storefronts and gritty hotels, rented for them by the Catholic organization Caritas. They bathe out of buckets on the side of the road or on rooftops, and cook on hotplates hooked up to gas cylinders.

The municipal and state governments are working on renovating a building for the migrants living alongside the bus station. But the leader of the indigenous group, Anibal Jose Perez Cardona, who was a social worker in Venezuela and whose father is the chief of their village, said it has low ceilings and is unbearably hot.

“We are sad because our situation is very hard,” Cardona said, his 3-year-old son Naru sleeping in his arms. “And we’re in another country now, so we can’t complain. There’s just no solution in sight.”

Manaus Mayor Arthur Virgilio Neto recognizes that the obstacles his city is facing won’t be overcome without all levels of government being involved. He also said the participation of the United Nations is essential.

“I know we have to act quickly, but this is a task that is beyond me,” Virgilio said. “We’ve already taken in as many as we can. [More would be] putting a lot of extra weight on someone who has other responsibilities. We can’t let services for Brazilians deteriorate too.”

Cardona had just registered Naru to start school in Mariusa when the family had to leave because of a lack of food. Both he and Quiñonez want their children to be integrated into the education system in their new city, while Quiñonez also hopes they can work with Brazilians to better understand each other’s languages and cultures, which have been the biggest barriers for the Warao since arriving in Manaus.

Most of the Warao speak only their own language. The few who speak Spanish translate for them when speaking to Brazilians, whose native language is Portuguese. While Spanish and Portuguese are close enough that Spanish speakers can get by on basics, they generally have to find a Brazilian who speaks Spanish to be able to communicate well with the people in their new country.

Even though they have received donations of food and clothing, the Warao still have to make ends meet by selling their artisanal products on the streets and at traffic lights, a task mostly taken on by women. When they run out of items to sell, they resort to begging for change, something the Warao say they wouldn’t do if they had other options. The municipal government has told them they need to stop.

“We’ve told them that all we want to do is work,” Quiñonez said of his conversations with government officials. “Nobody understands the size of the problem in Venezuela. I’m very sad to have nothing to do here.”

In Manaus, respiratory and skin infections — such as Quiñonez’ tick problem — have become the most prevalent health issues facing the Warao. Public health nurses, doctors and dentists have been visiting the camp and buildings where they live, giving them vaccinations and medications to prevent disease and fight illnesses they may have contracted during their journey to Brazil. The language barrier and cultural differences often make it difficult to explain the importance of these treatments, although interpreters have been helping.

Two small children died of pneumonia before the medical visits began, including 10-month-old Fernanda Rattia, who was in Manaus just one week before being hospitalized for two days.

“The doctor said she was already in a bad state,” said her father, Simon Rattia, slowly squeezing his eyes shut as he leaned on the doorframe of the room he now shares with his wife, their 10-year-old daughter, his brother and nephew.

His wife, he said, was inconsolable when their baby died, but just three days later she was back out on the street, trying to sell the few items they have left to sustain themselves in Brazil. She knows it’s the only way for them to survive in Manaus, and the family doesn’t expect to go back to Venezuela anytime soon.

“Nothing will ever get better in Venezuela,” Rattia said.

ALSO

The politician with the most at stake in Mexican governor's race isn't even running

Bloodshed, fires and chaos as thousands march in Brazil to demand president's ouster

Argentina learns a lesson: You don't cross the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza

Langlois is a special correspondent.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.