Given his abysmal human rights record, if Rodrigo Duterte was not Philippines’ president would the U.S. let him in?

- Share via

He’s admitted to personally killing people while he was a mayor, acknowledged that he supports death squads and boasted of his authoritarian leadership style. But that hasn’t prevented Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte from being invited to the White House.

Administration officials have defended the invitation President Trump extended last week, saying it will help repair relations between the U.S. and the Philippines — which reached a veritable low during the Obama administration — and build Asian support for countering an increasingly recalcitrant North Korea.

Duterte has been quoted as saying he may be too busy to show up in D.C.. But that hasn’t tamed the barrage of condemnation from critics who say his human rights record is so abysmal that if he weren’t a head of state he would be barred from entering the U.S.

They have a point. Here’s why.

First, here’s how regular people get permission to come to the U.S.

The Immigration and Nationality Act establishes the types of visas available and the conditions that must be met before an applicant can be issued one. Visa applicants must pass certain health checks, be fingerprinted and interviewed in person. It’s up to a consular officer at a U.S. Embassy or consulate to determine whether an applicant qualifies.

There are many reasons somebody might be denied, including human rights violations

Having a communicable disease of public health significance, failing to provide proof of vaccination against certain preventable diseases such as mumps and measles, or having a physical or mental disorder that is determined to be a threat are all grounds for denial.

So are convictions for certain crimes, including rape, murder and incest. The U.S. also bars drug traffickers, money launderers, suspected terrorists or members of the Communist party or any other totalitarian party.

“Certainly human rights violations would meet the definition of criminal grounds,” said Niels W. Frenzen, an expert on immigration and refugee law at USC.

By law, participants in Nazi persecution, genocide or the commission of any act of torture or extrajudicial killing are not eligible to receive a visa, according to the State Department. And those who have engaged in the recruitment or use of child soldiers are also barred.

Presidential Proclamation 8697, which was signed by President Obama in 2011, states that “any alien who planned, ordered, assisted, aided and abetted, committed or otherwise participated in, including through command responsibility, war crimes, crimes against humanity or other serious violations of human rights,” is not eligible for a U.S. visa.

So Duterte would probably not be allowed into the U.S. if he weren’t a president

Experts said he would likely not be granted a visa based on several of the criteria that make a person ineligible.

As part of his anti-drugs campaign, Duterte has publicly encouraged vigilante killings, allegedly paid police to kill suspected drug offenders and threatened to slay journalists, human rights activists said.

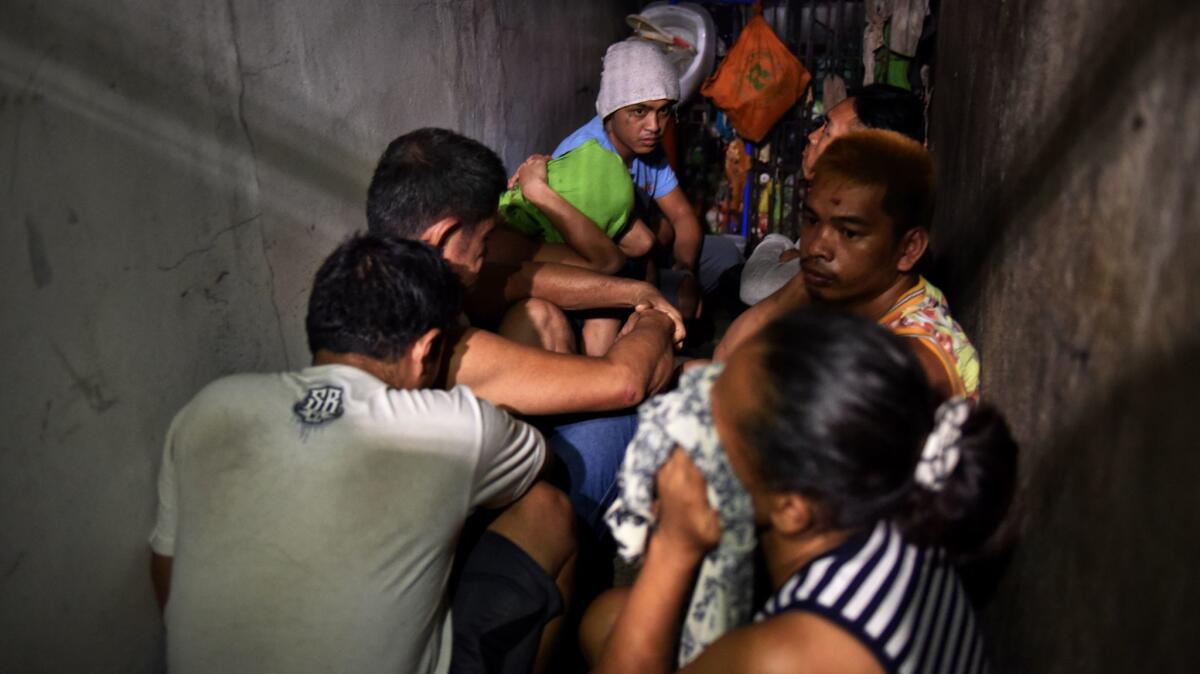

Since Duterte took office on June 30, 2016, “police and unidentified gunmen together have killed more than 7,000 suspected drug users and dealers,” Human Rights Watch reported in April. A Filipino lawyer has filed a complaint with the International Criminal Court in The Hague accusing Duterte of crimes against humanity and mass murder.

Human Rights Watch said Duterte has “been dirty for a long time,” and the agency has called on the United Nations to create “an independent, international investigation into the killings to determine responsibility, and ensure mechanisms for accountability.”

But of course he is a president. Heads of state still need a visa to visit

“Diplomats and other foreign government officials traveling to the United States to engage solely in official duties or activities on behalf of their national government must obtain A-1 or A-2 visa prior to entering the U.S.,” a State Department official said in an email. “Heads of State or Government must obtain an A visa regardless of the purpose of travel.”

Applicants for this type of visa are subject to “limited ineligibilities,” the official said. They don’t have to have their fingerprints taken and they may forgo the personal appearance interview.

But all the other rules apply, including restrictions on human rights abusers.

But there is some wiggle room

Waivers in the immigration act allow the State Department not to enforce certain conditions, except for genocide and espionage, Frenzen said.

“The secretary of State does have the legal authority to waive the grounds of inadmissibility for those who have committed extrajudicial killings,” Frenzen said.

In addition, the 2011 presidential proclamation states that the secretary of State, in consultation with the secretary of Homeland Security, could decide that a person who would otherwise have been barred entry should be allowed in because “the entry of such person would not harm the foreign relations interests of the United States” or “would be in the interests” of the nation.

Duterte wouldn’t be the first foreign dignitary blocked from the U.S. if the Trump administration decided to deny him entry

Among those currently barred is Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe, a target of U.S. sanctions since 2001 because of political violence and intimidation and “the Zimbabwean government’s increasing assault on human rights and the rule of law,” according to the State Department.

Until he became India’s prime minister in May 2014, Narendra Modi was not allowed to set foot in the U.S. In 2005, he was denied a U.S. visa over accusations that he failed to stop religious pogroms in which hundreds of mostly Muslims citizens were killed in Gujarat state, where he was serving as chief executive.

In January, the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo refused to issue a diplomatic visa to Bosnian Serb nationalist leader Milorad Dodik several weeks after he was reportedly invited to President Trump’s inauguration, according to Reuters. Dodik faces sanctions for “actively obstructing efforts to implement the 1995 Dayton Accords that ended the more than three-year war in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” the news agency reported.

In 2014, President Obama signed into law a bill that blocked Hamid Aboutalebi, Iran’s would-be ambassador to the United Nations, from entering the U.S. The law allows the president to deny admission to any diplomat who “has been engaged in terrorist activity against the United States or its allies and may pose a threat to U.S. national security interests,” The Times reported.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.