Column: The economic riddle for 2018: Will the middle and working classes see any gains from the big tax cut?

The U.S. economy was the feel-good story of 2017 — the pace of real economic growth rising strongly and the stock market playing out a euphoric high. Corporate profits are at a record high and job growth is moving toward the level that economists consider full employment.

But that came among many feel-bad subtexts. President Trump and congressional Republicans worked hard to undermine the Affordable Care Act. They failed to enact a long-term reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which provides coverage for 9 million low-income children and pregnant women.

Trump introduced an almost medieval hostility to science into government policies on environmental regulation, climate change and programs aimed at stemming teen pregnancy and providing contraceptives to women at no charge. That approach to governing will make some of its consequences known in 2018, but could also have an impact on Americans’ quality of life for years, even decades, to come.

Republicans aren’t making any connection to the $1.4 trillion the tax cuts will add to the deficit, but Democrats are sure to make the connection for them.

— Drew Altman, chief executive of the Kaiser Family Foundation

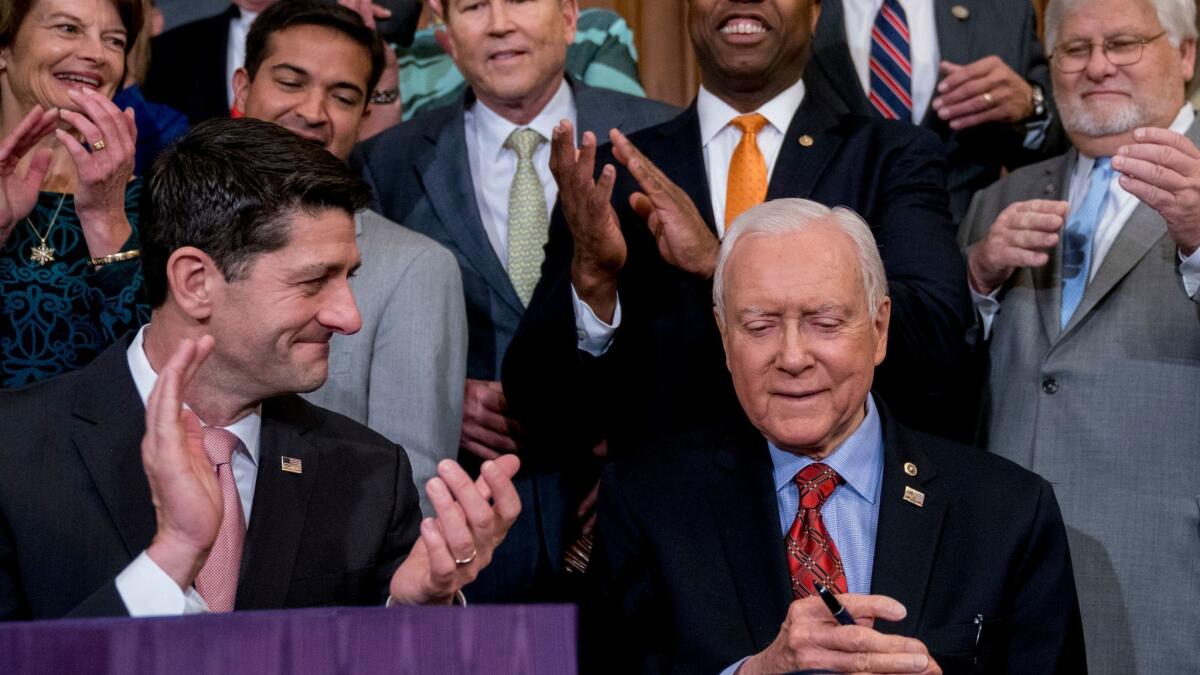

Republicans are hoping — indeed, bragging — that millions of households will be gratified to see higher take-home pay in their paychecks starting early in the year, thanks to the tax bill signed by President Trump just before Christmas. The GOP asserts that the bill’s centerpiece, a cut in the top corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%, also will spur business growth that will trickle down to the working class through more jobs and higher pay.

But many people won’t see much of a difference on their pay stubs. Workers earning $75,000 a year will see an average tax reduction of a bit more than $870, according to the Tax Policy Center. That would amount to about $17 a week, compared with gross weekly pay of $1,442. The sum could be swamped by larger deductions for items such as employer-sponsored health insurance, the employee cost of which has been creeping up, even as deductibles and co-pays rise.

For workers who earned more than $127,200 in 2017, and therefore may have enjoyed a few weeks or months without payroll deductions for Social Security late in the year, that tax will reappear as of Jan. 1, concealing much, if not all, of the tax cut. Inflation is forcing the maximum income for the Social Security payroll tax to $128,400 in 2018.

The real question is how much of the tax benefit will be distributed by employers to their workers. Early indications are none too promising. Continuing a trend that has vastly exacerbated income and wealth inequality in the United States, many large corporations already have made clear that their primary concern will be the welfare of their shareholders.

“Is it our goal to increase return to our shareholders and do we have an excess amount of capital?” Wells Fargo CEO Tim Sloan asked rhetorically at a Goldman Sachs investment conference on Dec. 5. “The answer to both is yes.” He said the bank expected to increase its shareholder dividends and share buybacks “next year and the year after that, and the year after that.”

Goldman Sachs predicts that Wells Fargo’s profit will increase 18% in the coming year, thanks to the corporate tax cut. The bank earned $22.8 billion in 2016, implying a gain of roughly $4 billion. What will be the employees’ share? The bank said it would raise the minimum wage of its workers by $1.50 an hour, to $15; if all 36,000 of the workers receiving a pay raise will be getting the $1.50 increase, that would come to $112.3 million. But the bank also announced a share buyback of $11.5 billion from mid-2017 through mid-2018 (on top of $8.3 billion repurchased in 2016-17). That’s the shareholders’ piece.

As my colleagues Jim Puzzanghera and James Rufus Koren revealed on Dec. 21, Wells Fargo initially tied the raises to passage of the tax bill, then maintained that the decision was independently reached — indeed, the company had announced some raises in January — and then backtracked again, asserting that the raises were the “result” of the tax cut.

There’s reason to doubt the sincerity of not only Wells Fargo, but other companies that tied announcements of raises and bonuses for the rank-and-file to passage of the tax bill. By doing so, they gave Trump and congressional Republicans the chance to preen over their legislative prowess.

But claims that the tax bill will spur more hiring and capital investment are dubious. The last time corporate America received a big handout based on similar promises, a 2004 amnesty for profits repatriated from overseas — $312 billion brought back at a tax rate of only 5.25% — companies responded to the tax break by handing out bounties to investors in the form of stock buybacks by the tens of billions while laying off workers by the tens of thousands. The 2017 tax bill offers corporations a similar preference, albeit not quite as generous. On the other hand, they have much more money to bring home today than in 2004 — possibly $2 trillion in cash and other assets.

Several big companies have handed Trump a public relations gift by explicitly linking pay raises, workforce expansions and employee bonuses to passage of the tax bill. These assertions should be taken with a grain of salt.

For one thing, “guarantees” of job security reached with Trump looking over CEOs’ shoulders appear to be written in disappearing ink with a half-life of a few months. Just six months after Carrier Corp. reached a highly touted agreement with President-elect Trump to keep a plant in Indianapolis instead of moving it to Mexico, the company launched two rounds of layoffs that would cut employment there by more than 600.

Another is that bonuses are a cheeseparing way to deliver pay gains. They’re not raises, which become permanently baked into an employee’s pay scale. They’re one-time handouts that may or may not be renewed the next year.

Share buybacks, however, are forever. From the Senate’s passage of the corporate tax cut on Dec. 2 through Dec. 15, new or increased stock buybacks totaling more than $70 billion were announced by 29 corporations, led by Home Depot ($15 billion) and Oracle ($12 billion). The figures were compiled by the Senate Democratic Caucus.

If there’s a silver lining in this wholesale handout to corporations and their shareholders, it’s that the tax bill could complicate any efforts to cut Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid or other social programs such as food stamps. That’s the view of Drew Altman, CEO of the Kaiser Family Foundation, who observed shortly before Christmas that it will be hard for the GOP to fight the appearance that cuts in those programs are being proposed to pay for tax cuts manifestly weighted in favor of the wealthiest Americans.

“Republicans aren’t making any connection to the $1.4 trillion the tax cuts will add to the deficit, but Democrats are sure to make the connection for them,” Altman wrote on Axios. Kaiser Family Foundation polling shows that the public is vastly opposed to cutting Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid to pay for the tax cuts.

But the single-minded focus of the Trump White House and congressional majority on serving their donor class should make middle- and lower-income Americans very uneasy in 2018. The rush to pass the tax bill left the reauthorization of the state-federal Children’s Health Insurance Program in the dust. CHIP’s federal funding expired on Sept. 30, but it was not until Dec. 21 that Congress passed a funding extension — and that good enough only to cover the program through March. Even with the extension, the continuing uncertainty about CHIP’s long-term funding has forced several states to warn enrollees that they may lose benefits in the near future.

Also uncertain is the future of the Affordable Care Act. The tax bill nullified the ACA’s individual mandate as of Jan. 1, 2019, knocking out a prop that encourages even young and healthy people to join the insurance pool.

It’s unlikely that the provision will be tantamount to repealing the ACA, as Trump claimed. But it’s likely to strike hard at Americans who buy individual health policies but earn too much to receive government premium subsidies (the ceiling will be $98,400 for a family of four in 2018 — a solidly middle-class income). Insurance companies will probably factor the likely decline in the health profile of ACA plan buyers into their rate increases for 2019 — which will start coming out in the spring, just when the 2018 congressional campaigns begin.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.