The Falcon Heavy rocket will be one of SpaceX’s biggest tests yet

With 27 engines generating 5.1 million pounds of thrust at liftoff, the Falcon Heavy rocket is one of SpaceX’s most ambitious projects yet.

And now, with questions swirling about the reported loss of the classified Zuma satellite that lifted off Sunday on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, the highly anticipated Falcon Heavy demonstration launch later this month may have taken on even more importance for the company’s military and intelligence prospects.

The new rocket gives the Hawthorne space company heavy-lift capability, meaning SpaceX could hoist massive satellites for commercial customers or lucrative national security missions.

As SpaceX looks to increase its share of defense business, those customers are very much interested in reliability, said Carissa Christensen, chief executive of consulting firm Bryce Space and Technology. For good reason: Zuma, for instance, reportedly cost more than $1 billion.

“Now is not a good time for questions about SpaceX’s ability to deliver what that community wants, which is reliable performance,” she said. “That community will be paying attention.”

Christensen noted that SpaceX has been unambiguous in defending its role in Sunday’s launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. As reports began to bubble Monday that the Zuma satellite may have plunged back toward Earth, the company issued a statement: “We do not comment on missions of this nature; but, as of right now, reviews of the data indicate Falcon 9 performed nominally.”

On Tuesday, SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell released an even stronger statement and pushed back against reports that a second-stage malfunction may have been to blame, saying that “after review of all data to date, Falcon 9 did everything correctly on Sunday night.”

“If we or others find otherwise based on further review, we will report it immediately,” she said. “Information published that is contrary to this statement is categorically false.”

SpaceX has continued on with preparations for the Falcon Heavy, which was scheduled for a brief “static fire” test this week, and an upcoming Falcon 9 launch for satellite operator SES and the Luxembourg government. Analysts say that further indicates the company did not see a problem with its rockets.

An SES spokesman said the company was in constant contact with SpaceX and is “totally confident” for its launch date at the end of the month.

Little is known about the Zuma satellite — not even the name of the U.S. government agency that owns it. The payload was intended to be launched into low-Earth orbit.

Defense giant Northrop Grumman Corp., which built Zuma and procured the launch service from SpaceX, said in a statement Monday: “This is a classified mission. We cannot comment on classified missions.”

SpaceX was certified by the U.S. Air Force in 2015 to carry national security satellites, a move that broke up a longtime and lucrative monopoly held by a joint venture of Boeing Co. and Lockheed Martin Corp. called United Launch Alliance.

Last year, SpaceX launched two national security missions with its workhorse Falcon 9 rocket. The company has said it plans to seek certification from the Air Force for the Falcon Heavy for future national security launches.

SpaceX found that developing such a huge rocket was more of a challenge than initially expected. Falcon Heavy was first announced to the public in 2011, with company Chief Executive Elon Musk promising a demonstration flight by the end of 2012.

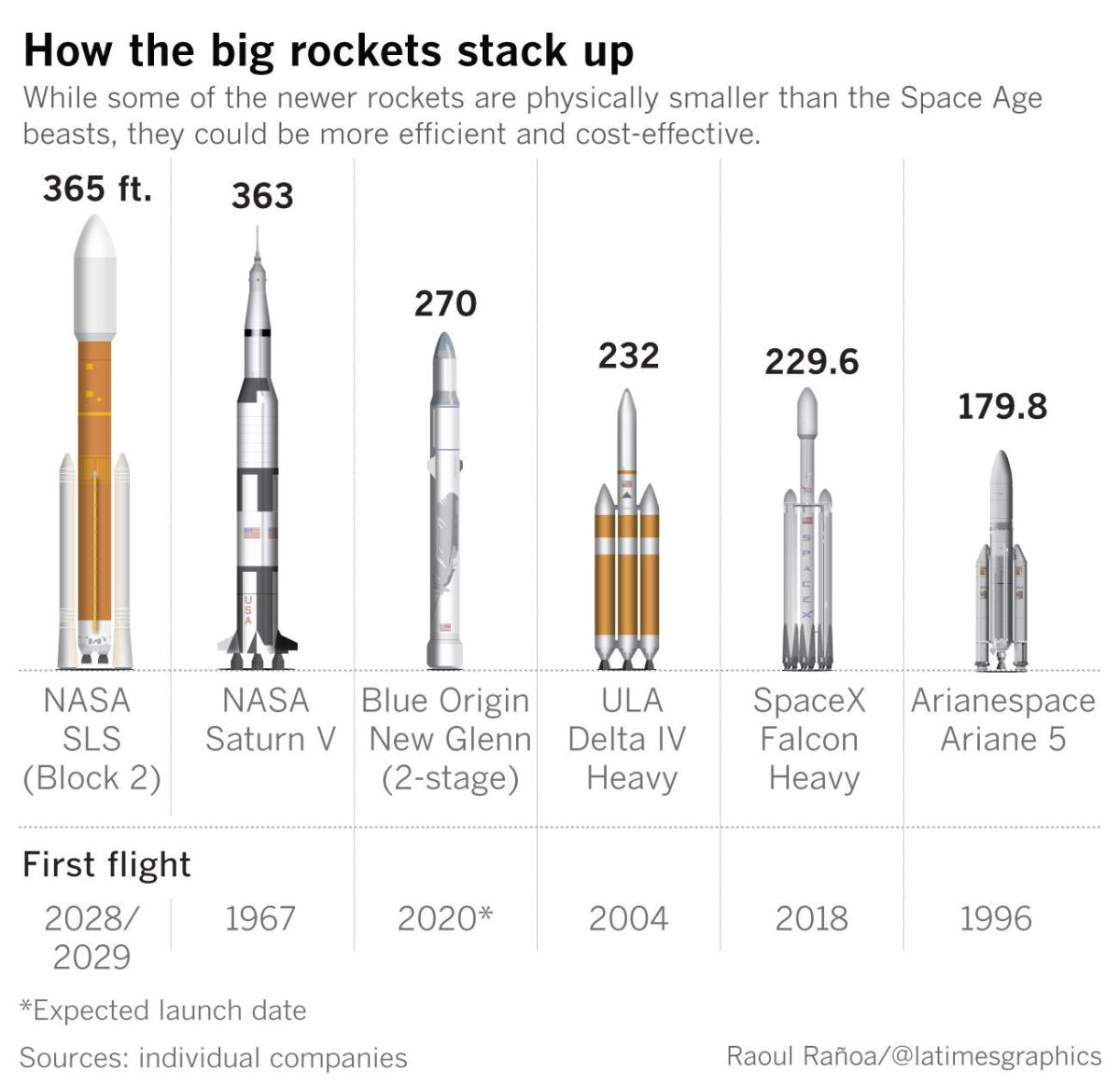

Falcon Heavy is just one of several heavy-lift rockets currently under development by commercial companies and NASA. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin has unveiled plans for a rocket called New Glenn, which will eventually be available in two-stage and three-stage versions. ULA has proposed a new rocket called the Vulcan that would replace its current intermediate and heavy-lift vehicles. Orbital ATK is looking to develop its first intermediate and heavy-lift vehicles known for now as the Next Generation Launcher. And NASA is continuing work on its Space Launch System.

SpaceX has plans for an even larger reusable rocket and spaceship system called BFR, which would eventually replace the company’s current lineup. Musk has said BFR could be used for missions ranging from taking satellites to low-Earth orbit to colonizing Mars.

“If we’re talking about expanding exploration, it will be good to have more capabilities,” said Olga Bannova, research associate professor and director of the space architecture graduate program at the University of Houston’s college of engineering.

In the meantime, Falcon Heavy, like its smaller cousin the Falcon 9, will advance SpaceX’s goal of cutting launch costs by reusing rockets. After the demonstration launch, SpaceX will attempt to land all three engine cores — two on land-based pads and one on a sea-based droneship — in a feat Musk has described as a type of “synchronized aerial ballet.”

Falcon Heavy launches start at $90 million, compared to the starting price of $62 million for the smaller Falcon 9, according to SpaceX’s website. ULA has advertised the starting cost of its Atlas V rocket at $109 million. The venture’s larger Delta IV rocket — the most powerful rocket currently used by the Air Force to carry military satellites — is being phased out because it is costly to produce.

However, Musk has also tried to downplay expectations for this demonstration launch, saying there was a “good chance” the rocket would not make it to orbit on its first go.

The Falcon Heavy will be carrying Musk’s midnight cherry Tesla Roadster as its payload to ensure that the rocket works with heavy cargo aboard. Musk has said on Instagram that the car will be launched on a “billion-year elliptic Mars orbit.”

In the past, the first few launches of a new rocket were expected to have a fairly high failure rate. But modern computer modeling and analytics have changed that expectation.

A strong showing on Falcon Heavy’s first outing will enhance the perception of SpaceX’s capabilities and will also contribute to the view of its market value, Christensen said. But a failure would not be “devastating,” she said, noting that the company is given credit for its ambitious goals.

The Falcon Heavy also benefits from the development of its predecessor, the Falcon 9, said Phil Larson, assistant dean at the University of Colorado, Boulder’s College of Engineering.

“They know the Falcon 9 well,” said Larson, who formerly worked at SpaceX and was a senior advisor for space and innovation in the Obama administration. “They already have a lot of great data, and I think this sets them up well for this demonstration launch.”

Twitter: @smasunaga