Chef Jordan Kahn’s weird, expectation-defying, silly ambitious culinary dream

Under the dome of a dark, nighttime sky, after dinner service at his restaurant Vespertine, chef Jordan Kahn is talking to diners in the garden, an arrangement of seats and greenery next to the restaurant and near a fountain. To the uninitiated, this probably sounds like a peaceful, even pastoral scene. Maybe a man in chef’s whites, running water, edible flowers, and inside, a rustic dining room, open kitchen.

But Kahn doesn’t much look like a chef and his restaurant looks not at all like a restaurant. None of the rest of it fits either: The garden is built of spiky plants and heated blocks of cement and telescopes; the fountain looks like a fluorescent pile of rocks. Kahn’s dishes, though expertly orchestrated from seasonal ingredients, are sometimes indistinguishable from the ceramics they’re presented with, resembling not so much food as objets d’art.

Expectations are funny things. Before Vespertine opened, in July, there were rumors that Kahn was opening not an experimental, highly ambitious, tasting menu restaurant, but a waffle joint, although mostly because of the conundrum of the building itself: an Eric Owen Moss project called “the Waffle,” a bendy glass-and-steel checkerboard structure that looks like Salvador Dali’s idea of a waffle iron.

Kahn himself had purposefully blurred expectations, first opening another restaurant across the street, a breakfast-and-lunch spot called Destroyer, then releasing a teaser video preview of Vespertine, a short film that baffled pretty much everyone who saw it. (Imagine a “Star Wars” trailer done by Ingmar Bergman.) When Kahn talked about the new restaurant, or posted to Instagram, it was in cryptic messages that seemed more like he was describing a JPL project or an Ursula K. Le Guin adaptation instead of a restaurant.

“As pretentious as so much of this may seem,” Kahn says now, “it has to be that way. Because it’s the only way people are expecting the unexpected.” Maybe so, but the backlash has been as over-the-top as Kahn’s restaurant. (Two of the best headlines: “Vespertine Is Not a Spaceship, It’s a Wizard’s Tower” and “Edible Doom And Gloom: L.A.’s Most Expensive New Restaurant Wants to Depress You for Dinner.”)

A slight man with dark hair cut in jagged edges around a pale, expressive face, Kahn is as likely to reference Sigur Rós and “True Detective” as he is outer space — or Thomas Keller and Grant Achatz, two of the chefs with whom he’s worked.

It was work that began early, when Kahn was a teenager, and any triangulation of Kahn as a chef should give the fixed points of Savannah, Georgia, where he grew up, and Yountville, Calif., where he began his career, as a 17-year-old intern at Keller’s French Laundry.

Kahn likes to tell the story of how his mother gave him a copy of “The French Laundry Cookbook” on his 13th birthday, and how he became obsessed with it, reading it behind textbooks in high school at the Savannah Arts Academy (he was a drummer), and memorizing the recipes he had no idea how to cook. How that obsession propelled him at 16 to cooking school, at Johnson & Wales in Charleston, S.C., where he graduated from the two-year program in eight months. How it resulted in a handwritten, eight-page letter to Keller himself.

It was “an obnoxious letter, professing my love for him,” says Kahn now, at 34 both still proud and a bit sheepish. And that letter, in turn, resulted in Keller offering Kahn a stage, or unpaid internship, at the restaurant of his youthful dreams. So he drove cross-country in two days, started work and, when the internship ended, stayed on, working with Sebastien Rouxel in the pastry kitchen. Two and a half years later, Keller tapped him to help open Per Se in New York. A one-year stint at Achatz’ Chicago restaurant Alinea followed. Then a short stay at Varietal in New York, then to Los Angeles and Michael Mina’s XIV, where he met his fiancée Gloria Peña (now one of Vespertine’s black-clad servers and its general manager) and Noah Ellis, with whom he opened his first restaurant, Red Medicine. Kahn hadn’t yet turned 30.

Kahn had grown up cooking with his grandmother, who had fled Cuba with her family when his mother was a teenager. His parents had met in Port Chester, N.Y. — his father is from Queens — and had eventually settled in Savannah, where his father was stationed in the Army. “I was always interested in eating and cooking; watching Graham Kerr, Jacques Pépin, ‘Great Chefs’ on PBS,” says Kahn, who still seems more like a shy, goofy art student than a classically trained chef.

What Kahn trained to be, it bears repeating, is a pastry chef. In itself this is not terribly unusual — Yotam Ottolenghi and Alex Stupak, with whom Kahn worked at Alinea, both started as pastry chefs — but much of what Kahn is now doing at Vespertine traces to the pastry kitchen.

“Pastry is all about form and manipulation,” says Kahn, who acknowledges that he has “a difficult time doing less with things.”

Another of Kahn’s origin stories is how he found the building that would become Vespertine. After service at Red Medicine, the Vietnamese-Nordic restaurant that had a four-year run in Beverly Hills, around 3 a.m., he’d drive to Culver City’s Hayden Tract and break into Moss’ building, still under construction. He’d spend hours inside, among the scaffolding and the empty windows, just thinking. After weeks of this, he finally called the number on the For Lease sign, only to be laughed at when he said he wanted the place for a restaurant. But Kahn persisted, by then obsessed with the space.

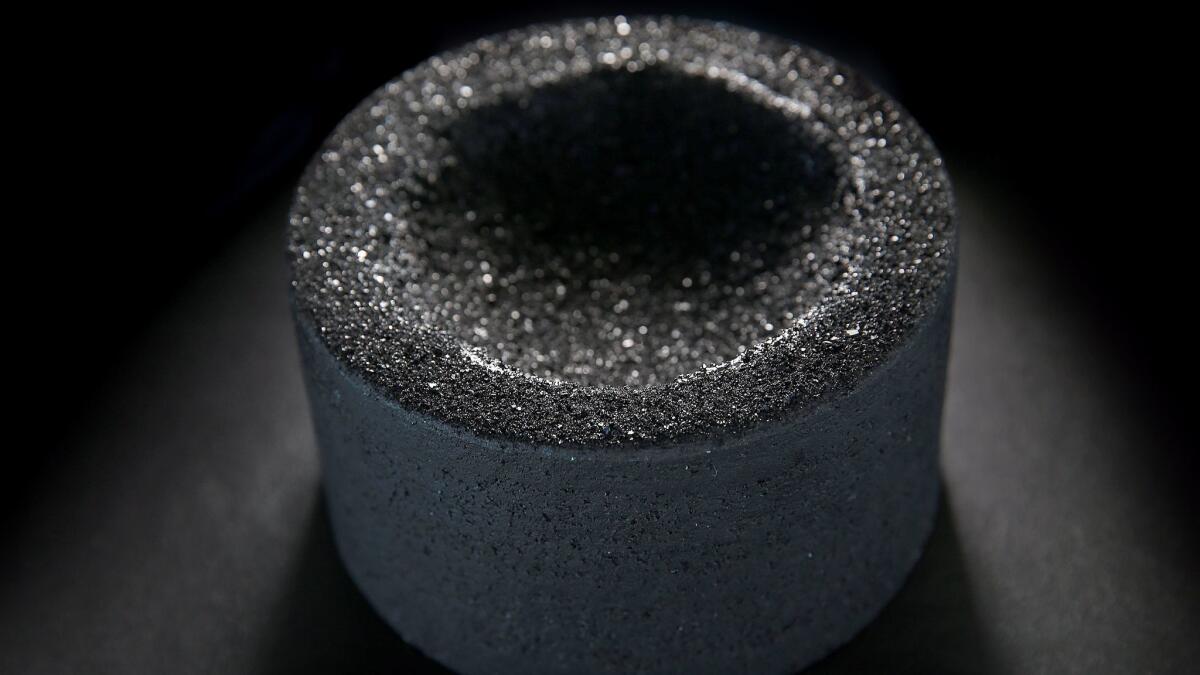

When he was at Red Medicine, he was known for assembling small gardens of food inside what looked like globe terrariums. At Vespertine, you can see that lineage in some of the bowls, the sauces, seafood and produce and leaves, all perfectly arranged. The difference is that Kahn has taken it further, incorporating the food into the dishware itself, purposefully blurring the boundary between the two. So a bright rectangle of mango comes wedged into an obelisk; a mixture of raw fish and who knows what else is under a strata of teff, burnt so that it’s indistinguishable from the rough obsidian of the bowl it comes in.

What Kahn is playing with, of course, is permanence, and the problem all chefs have, especially those who are particularly aesthetically-minded, when they spend so much time creating beautiful things, then watch the rest of us eat them.

“You’re making something over and over,” says Kahn, “that’s immediately destroyed.” Marie-Antoine Carême, the legendary Revolution-era French chef (who also trained in pastry), made his name constructing enormous sugar centerpieces. The appeal of architecture, one of the more permanent of artistic vocations, isn’t difficult to see.

Fixating on the culinary mechanics of the seen and the invisible is something of a through line for the chef, the culmination of a series of obsessions. And this can seem either charming or maddening, ambitious or pretentious, too-serious or kind of silly — a nightly art installation or dinner. Expectations are funny things.

Vespertine’s kitchen (surprise!) doesn’t look like a kitchen either. You get a glimpse of it on the way to dinner, when you’re pit-stopped by your server on the second floor to greet Kahn. There are the black-clad sous-chefs and the tubs of foraged plants; it looks like a science department lab. The black counters are made of Dekton, a pressure-treated glass. There are two combi ovens, an induction stove, two blast freezers, “a few” dehydrators and iSi syphons and bluetooth-controlled immersion circulators. The ceiling and the hood are covered with white acoustic plaster. Underneath one counter, there are jars of gummy bears and Reese’s Pieces: an incommensurate burst of both color and banality. (The chef’s engines, it seems, still run on sugar.)

“This is my version of the French Laundry,” says Kahn, looking skyward along and beyond the corrugated wall. Vespertine, of course, looks — and tastes — absolutely nothing like Keller’s restaurant. But to Kahn, with or without one of his garden telescopes, maybe it does.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.