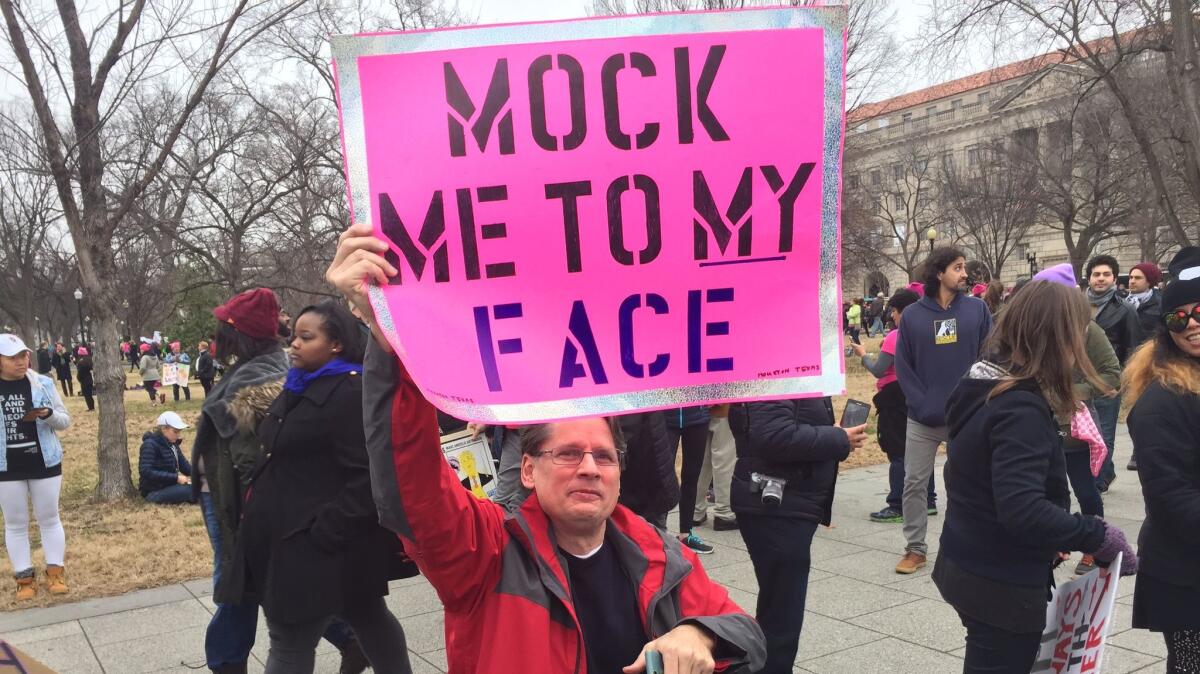

Column: Why this gay, disabled Texan went to the Women’s March to tell Trump: ‘Mock me to my face’

He had taken up a spot on the sidewalk near the end of the Women’s March, not far from the White House, and held a sign overhead for marchers to see.

“Mock Me to My Face.”

The middle-aged man wore spectacles and a red jacket, and he was perched on the seat of a four-wheel walker. I took a photograph with my phone, and it was later published by The Times. Obviously, his sign was a response to what the man, and many others, believed was a case of Donald Trump mocking a disabled reporter on the campaign trail in November of 2015.

I wanted to find out what the guy’s story was, but I was looking for a Los Angeles woman who marched with her two daughters, and we were texting each other our whereabouts. I hurried off in search of her, and never met the man whose photo I had taken on Jan. 21.

Then, on Monday, I got an email.

“My name is Rich Arenschieldt,” it said. “I’m the guy shown in the picture you took.”

Arenschieldt is a Houston resident and contributor to OutSmart Magazine. He’d written a story on his trip to the march, not yet published, for the magazine. A friend of his had spotted my photo in the L.A. Times, and Arenschieldt wanted to know if his magazine could use it for his story.

Arenschieldt sent me a copy of what he wrote and we later talked by phone. His story for the magazine begins with this line:

“‘We do not expect this child to survive…’ reads my pediatrician’s medical note, written on Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania stationery dated July 10, 1960.”

Arenschieldt weighed 3½ pounds at birth. He had severe cerebral palsy and endured surgeries, braces, casts and clinical trials.

“To everyone’s amazement,” he wrote, “I lived.”

Arenschieldt said that as a kid, he was mocked and bullied before there were anti-bullying programs. His parents had their reasons for not coming to his defense.

“My parents’ response was, ‘Well, don’t expect us to deal with this, you have to deal with this on your own. You have to figure out how to respond,’” Arenschieldt said. “My mother had this famous quote: ‘The world is going to be tough on Rich. I have to make Rich tougher.’”

It seems to have worked. Arenschieldt studied at Baylor University, became a banker, then ran a mentoring program for students interested in medical careers. He retired from full-time work a year ago, but as a gay man, he’s been a regular contributor to OutSmart for years. An editor there told me Arenschieldt’s Washington story will be published soon.

Arenschieldt said he hadn’t been a typical advocate for the rights of the disabled. Taking the cue from his parents, his approach has always been to live his life. But when he saw Trump single out a reporter with a physical disability, it awakened something in him.

Trump has insisted he was not mocking the reporter and didn’t know he was disabled. It’s an assertion that’s hard to buy if you’ve seen the video, in which Trump jerks his arms and twists as if he’s having spasms, and says, “You’ve got to see this guy.” The reporter has said he used to cover Trump regularly and they were on a first-name basis.

Arenschieldt isn’t swayed by Trump’s claim.

“When you see this kind of mocking taking place, you know what it is,” he said. “This is something a schoolyard bully does…. He can say what he wants, but those of us who have been on the receiving end of that kind of treatment knew exactly what it was. There is no doubt in my mind what that was, and it’s the hurtful intent, more than the mocking, that’s really important.”

Meryl Streep singled out that incident in a scathing attack on Trump at the Golden Globes ceremony, and she was widely praised. But some people with disabilities criticized Streep for suggesting that Trump picked on people he outranked in “privilege, power and the capacity to fight back.” As one California advocate told me, disabled people can fight their own battles, and they can also take the high road by refusing to dignify reprehensible comments.

Arenschieldt said he understands those views, and no one can take Trump any lower than he’s taken himself. But still, he was grateful to Streep.

We still have a long way to go in terms of prejudice in this country, not just in terms of race, gender and sexual preference, but in terms of disabilities.

— Rich Arenschieldt

“My attitude is that we still have a long way to go in terms of prejudice in this country, not just in terms of race, gender and sexual preference, but in terms of disabilities,” said Arenschieldt. “I’ll take allies wherever I can get them.”

Arenschieldt said he didn’t know what to write on his sign at first, but his anger helped guide him. If Trump had done the same thing to him in his presence, he said, “I’d have gone after him physically.”

“I thought, ‘Okay, you’re the world’s biggest coward. Come to my house and mock me.’”

Arenschieldt got on a plane and went to Trump’s house instead. He went to the march with a cousin’s wife, and was overwhelmed by “a deluge of compassion.”

Hundreds of people approached or gave thumbs up as they marched by. One tearful woman told him she had adopted two girls with cerebral palsy, and felt as though Trump had mocked them.

As a boy, Arenschieldt said in his story, “I managed the cruelty of my classmates and others by creating a détente of humor infused with the fierceness of a lion.

“Interestingly, it took the Women’s March on Washington to make me roar again.

“Hear me.”

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

ALSO

Supreme Court likely to boost public schools’ responsibilities to children with disabilities

Trump loathing unifies the diverse crowd at the massive L.A. women’s march

How the women’s march came into being

Trump should read about the Muslim foster father who cares for terminally ill kids

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.