Column: The California deal: Accepting the calamity along with the splendor

Yes, we have summer and at times a bit of winter, but the cycles in California follow a different calendar.

From drought to flood, from fire to mud, California bakes, burns and floats, always on the brink of calamity. We are here by the millions in defiance of reason, lured to a bountiful garden that at times seems unfit for human habitation.

Historic, wind-driven, end-of-the-world fires forced massive evacuations, destroyed thousands of homes and took lives in Northern and Southern California late last year. Then, as we began the new year processing the grim evidence that we are dangerously bone-dry this winter, we got welcome news that rain was finally on the way — rain, with a chance of waterspouts along the coast.

We know from experience that California has a script in which the first act is fire and the second is mudslides, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still be surprised by new versions of weather-driven weirdness. I saw video of a car bobsledding down a winding Burbank street on a raging river of mud.

And then there was unexpected tragedy in Montecito.

The rains, following the narrative, were not normal. Torrents fell with unanticipated force early Tuesday, half an inch in five minutes at one point, which a meteorologist called a 200-year rarity.

The fire-scorched Santa Barbara County earth gave way, the catch basins overflowed and lethal rivers of mud and debris thundered down on what had looked, deceivingly, like a safe little village of affluent utopia. The mud swept houses off their foundations, carried boulders all the way to the beach, turned the 101 into a river and buried people alive, including children.

“It was almost unimaginable what I saw today,” a Santa Barbara County public works official told The Times.

Oprah Winfrey, days earlier a presidential possibility, was just another Montecito resident with a yard full of mud, praying for neighbors who lost everything.

The mud stopped moving but the questions will continue to flow — about the urgency of evacuation orders and the failures of the emergency warning system.

And about whether, in a state built for disaster, we live too close to peril.

Twenty years ago, I rented a condo near Lincoln Boulevard and when I called to insure my belongings, an agent told me she’d have to look into the possibility of ocean flooding before quoting me a rate.

I was roughly a mile from the beach and figured this was just a ploy to jack up my rates. But who can know the limits of California’s capacity for natural disaster? One good earthquake and one little tsunami and surfers could be sampling the break at Lincoln and Rose.

In case you missed it in the deluge of weather-related catastrophe, yet another southern, venomous sea snake washed ashore in Newport Beach this week, many miles from home. The news broke about the same time we learned that two weeks ago, a part fell from an airborne jetliner and landed on a moving vehicle in Newport.

It remains unclear whether the yellow-bellied reptile was delivered by a waterspout, but I suspect three or four dozen “Sharknado”-inspired screenwriters are feverishly tapping away at single-origin coffee shops across L.A.

I could be wrong, but it seems to me that in a place where the air is charged by uncontrollable natural forces, there’s an impact on the human psyche.

We know there are sharks in the water, but we go swimming anyway.

We know the hillside could come crashing down, but we live in houses on stilts.

Risk, failure and rebirth are all possibilities in the contract we signed. And we know, under all the layers of denial about what lies beneath our feet, that the worst California disaster is yet to come.

But we don’t move to South Dakota.

On Thursday, I drove up to Mt. Wilson, where scientists have used powerful telescopes to study the universe for a hundred years. The great glory of California is on full display and the views offer a reminder of what makes this part of the world so attractive and dangerous at the same time.

To the west, the mix of sun and marine fog painted Santa Monica Bay in soft orange light. To the east, forested slopes of the Transverse Ranges stretched to snow-capped peaks formed eons ago where tectonic plates come together. A bend in the San Andreas fault became the architect of upward thrust.

Millions of Californians live close to topography like this, subject to the ravages of drought, fire, flood, fierce winds and potentially deadly earthquakes.

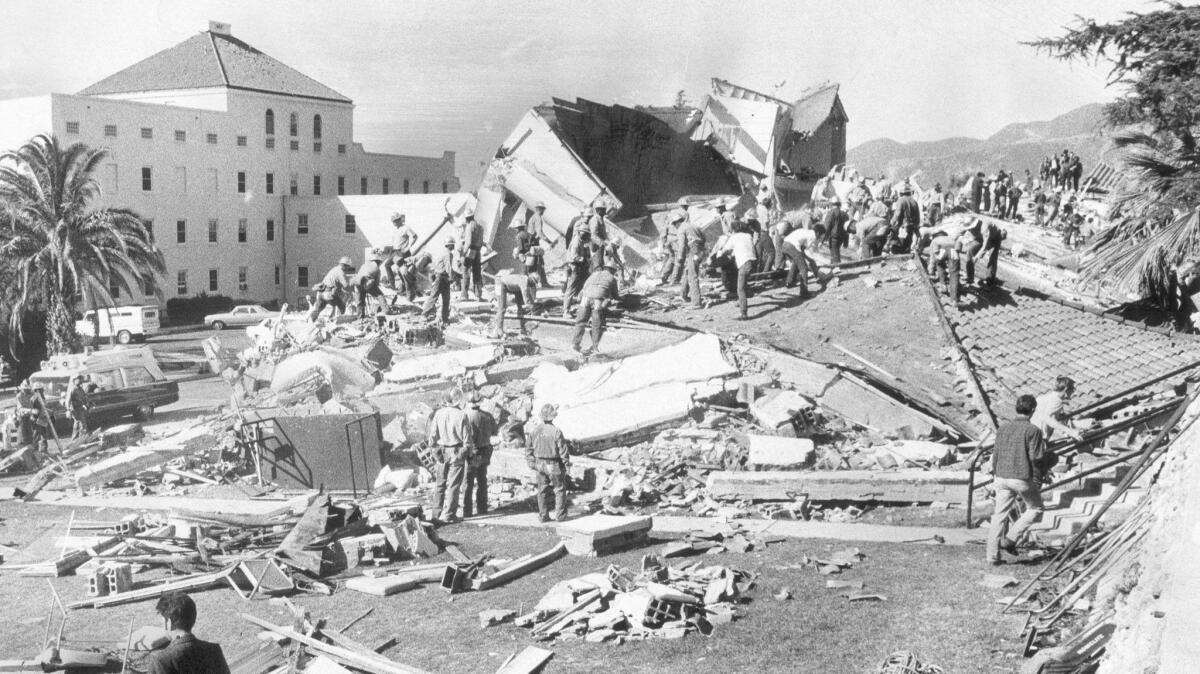

Steve Padilla, a telescope operator who studies sunspots, has lived on the mountain and enjoyed the views, the wildlife and the sound of the wind in the pines for decades. He recalls the 1991 Sierra Madre earthquake.

“I was having my breakfast,” he said. “And my bowl of cereal hopped off the table and onto the floor.”

Maggie Moran, operations manager at the Mt. Wilson Institute, occasionally sees bears when she runs the trails, and she’s developed a respect for both the beauty of the mountain and the threats all around it. She was asleep at her home in Arcadia early on the morning of Oct. 17 when a phone call awakened her.

“Mt. Wilson is on fire,” a colleague informed her, and she could see the flames from her kitchen.

“I threw my things together and drove up here,” she said, only to be evacuated later when a wall of flames climbed up to the peak and firefighters dropped retardant from planes and helicopters.

Fifty acres were scorched, and Moran warns hikers to stay clear of the area because the ground is now unstable and vulnerable, as we know all too well, to mudflows when it rains.

David Randall, a Boyle Heights resident, rode his bicycle up the steep, 19-mile incline from La Cañada-Flintridge to the observatory Thursday morning. He said he was 6 years old when the 1994 Northridge quake damaged his home, and that his sister’s friend was one of 51 people killed.

His shaken family moved to the East Coast, he said, but he recently decided to return to his home state, eager to make the bargain we all do.

He came back for the splendor, he said, but would rather do without the calamity.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.