Battling his demons from an old war, he goes extra mile for vets

Ric Ryan, fighting demons from an old war, is helping soldiers returning from the latest ones. In two years, his solitary walks on two bum knees have raised $19,000 for UCLA Operation Mend.

- Share via

Ric Ryan donates a quarter each time someone waves at him on his long walks. He has inspired others to donate too. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times) More photos

The Walking Man of Murphys, as he's known along a certain stretch of California 4 in Gold Country, sings.

Loudly.

"You've lost that loving feelin' ...," the ex-Marine croons, his off-key notes traveling across traffic on the two-lane road.

The freedom to sing poorly is one reason Ric Ryan is out here — day after day, in every season — his walking stick clicking briskly through the miles. He likes to have "time with my tunes, when nobody else has to listen," he said.

But he's also following unexpected paths of grace.

Ryan, 67, is fighting demons from an old war while helping soldiers returning from the latest ones. In two years, his solitary walks have raised $19,000 for UCLA Operation Mend, which offers free reconstructive surgery to disfigured soldiers and Marines. (About $4,000 has come from his own pocket, a quarter at a time.)

When he began walking, the Vietnam veteran didn't know he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder — or at least didn't know that was what it was called.

An otherwise kind man, Ryan over the years displayed flashes of anger. When his mood turned dark, his family realized it was best to not ask questions. "He was loving. But our kids knew what it meant to grow up with a father who had been in Vietnam," said Joanne Ryan, his wife of 43 years.

As the sounds and images of Iraq and Afghanistan played out on television, Ryan heard of soldiers returning to no jobs, their families broken by repeated deployments. He began fixating on the bitter homecoming he and other Vietnam-era soldiers had faced. He grew agitated. He couldn't sleep.

"I wanted these ones coming home to be welcomed. Not treated the way we were," said Ryan, a wiry man with a crew cut and a limp from two bum knees.

One day, Ryan just went out walking — and kept going for 18 miles. When he came home, he lay down on the bed, shaking and crying. Joanne was scared for him. But it wasn't pain or exhaustion, Ryan said. It was release.

He began walking every day.

It wasn't the first time he'd covered ground to still his mind. As a teenager he'd walked halfway across the country after a fight with his mother. At 18, he joined the Marines. He spent his 21st birthday in a foxhole with two Schlitz beers, daydreaming about what it felt like to stroll free and calm and easy.

Ric Ryan waves to a motorist on California 4. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times) More photos

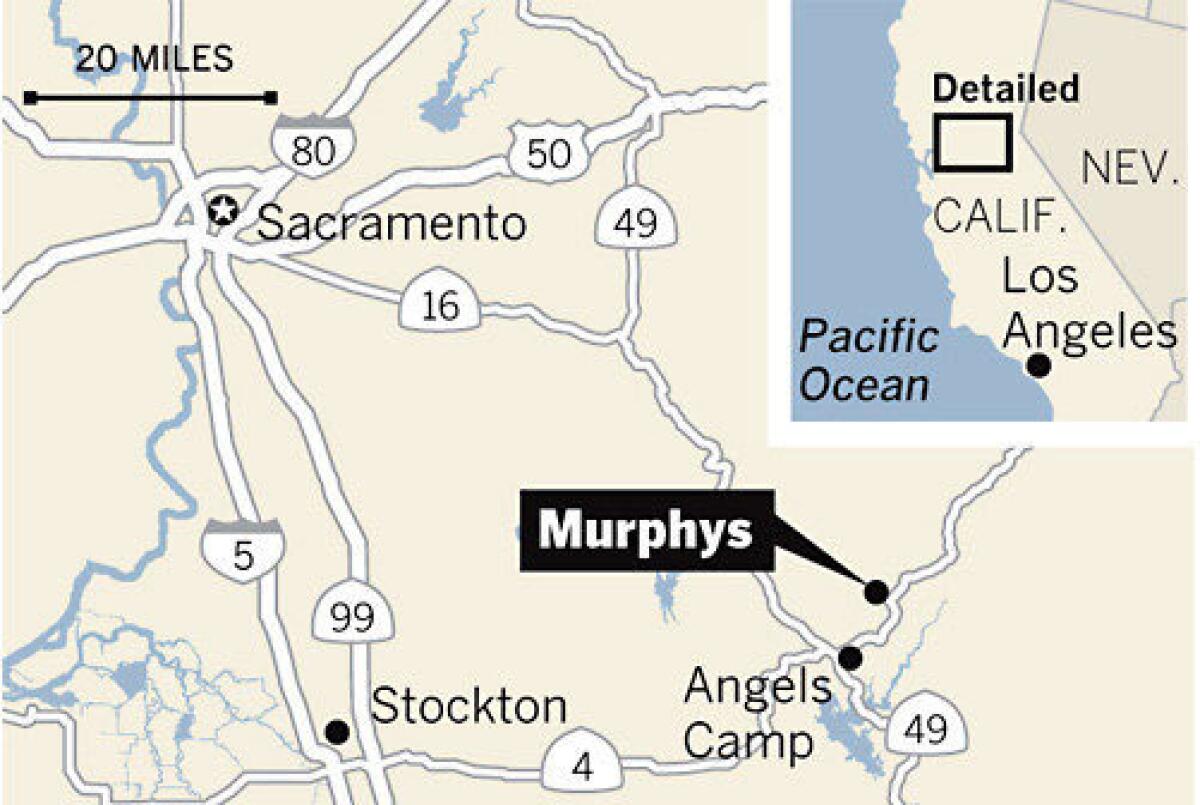

Murphys is a small town, population 3,000, and neighbors would wave at him as he walked. Some would honk — mostly to be friendly, but also because Ryan walks on a narrow shoulder along the curving highway, where people tend to drive too fast.

Those spontaneous greetings gave him an idea. Ryan had seen a documentary about Operation Mend. He decided to donate a quarter to the charity every time someone waved at him. During each walk, he kept a daily tally. Before he went home, the retired ironworker — who lives on his pension and Social Security — would go to his bank and deposit the $10 or $15 for that day.

Ryan thinks it must have been the bank clerks who first asked what he was doing. Word got around. A man stopped and gave him a roll of quarters. People in town started handing him checks made out to Operation Mend for hundreds of dollars. Jim Hereford, who owns Gold Electric (a business on Ryan's route), donated a bright orange vest to make him more visible. Ryan added a U.S. Marine Corps patch to the neon.

In December, Jeff German was driving from his home in Angels Camp to his auto shop in Murphys. He was in a bad mood. As on many mornings, he saw the orange flash of Ryan walking.

"There you got Ric — who I consider a real good person — out there carrying these demons, trying to change something he's battling into a positive for the veterans coming back now," German said. "You got Operation Mend trying to help these guys and gals who are going through so much. You got it all tied to a simple gesture of kindness like a wave hello.

"When I got to work I told Barbara, my office gal, 'Get Ric down here, I'm going to make an old man cry.'"

When Ryan arrived at the shop, there was a $2,500 check waiting for him. He cried.

Ryan wears braces on both legs and uses a walking stick. Years of playing soccer and marching in the Marines left him, he says, with knees that are down to bone on bone. But he still covers nine miles in two hours.

He takes every other Tuesday off from walking and drives 35 miles to the veterans' clinic in Sonora for treatment of what he now knows is PTSD. Shortly after he started his walking routine, he ran into an old buddy who told him that a group of guys were getting together at the clinic and he should check it out. He did, going on to graduate from an anger-management class and now faithfully attending group counseling with 20 other men.

Anyway, they told me I was already doing the best thing I could do: walking and giving."— Ric Ryan.

He's been told he needs to talk one-on-one about things he remembers, but the only private counseling available is by teleconference. He went once.

"The hardest thing I've ever done. And the doctor on a computer screen? Nope, not for me," he said, rolling his blue eyes and shaking his silver head. "Anyway, they told me I was already doing the best thing I could do: walking and giving."

On a recent Saturday, when the sky was an ever-changing swirl of white clouds against bright blue sky and the fields vivid green, Ryan parked his pickup at Tower Gas in Murphys and started marching. His back was ramrod straight. When someone waved, he'd flick a quick acknowledgment, keeping his hand at his waist. He only gave an honest-to-goodness wave a couple of times.

Some of the people knew their waves meant a quarter. Most didn't.

"It's not a secret," Ryan said. "If they ask me, I'll tell them. But I'm not the kind that likes to draw a lot of attention."

As he walked, he sang along to his MP3 player, interrupting himself somewhere along Mile 2 to say "Good morning, donkey" to the creature that always comes to the fence to watch him pass by.

The summer he was 15, Ryan walked from Seattle to South Dakota to find a man he thought might be his father. It wasn't the right man. But he spent every summer after that walking, hitchhiking and hopping trains.

"Just moving and looking at the countryside, that's part of me," he said.

Giving freely is also part of his history.

A few years ago, Ryan saw a story about a little girl selling lemonade to help her mother, who had cancer. He went to her stand, ordered a glass and paid with $1,000 in gold coins he'd been collecting. He didn't mention it to anyone until he told his wife a few days later.

"I suppose there was a part of me that thought, 'All $1,000? Would $500 have been enough?'" she said. "But I really love that part of Ric. He's a giving man."

Sources: ESRI, TeleAtlas (Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

Ryan said his contributions to Operation Mend are small.

"They auctioned off this Camaro in Texas to raise money, and one man paid $330,000!" he said. "One soldier's operations can run $500,000. But Operation Mend pays for everything. The guys and gals don't spend a dime of their own money. So I figure, even if my bit just pays for gas to get them to the airport or a ticket to Disneyland for their kid, it's helping."

Ron Katz, the Los Angeles philanthropist who gave $1 million in seed money to start Operation Mend, said Ryan's contribution is anything but small.

"Ric Ryan mesmerizes me. He's one man walking, without even a sign, just a passion to help this enormous cadre of wounded soldiers," Katz said. "The money he gives is an extraordinary contribution of hope."

Photos: The Walking Man of Murphys

Column One: More great reads from the Los Angeles Times