Congress is caught up in the sexual misconduct scandals. Will it police its own?

With a spate of sexual harassment allegations stirring trouble on Capitol Hill, Congress faces a new test of how well it can police itself.

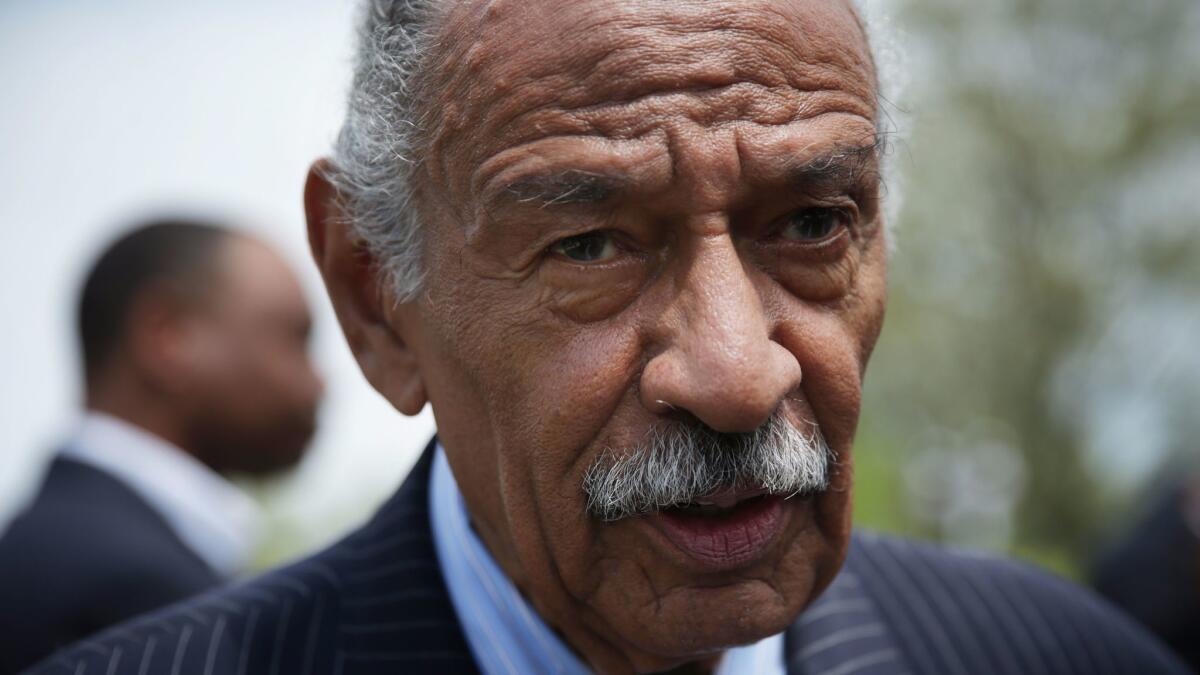

Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, accused of demanding sex from women who worked for him, is under investigation by the House Ethics Committee. Some fellow Democrats have urged him to resign.

Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota, another Democrat fighting to save his career, is bracing for a Senate Ethics Committee inquiry of groping allegations.

And GOP lawmakers have threatened to expel Republican Roy Moore of Alabama if he wins a Senate seat in a Dec. 12 special election. He stands accused of molesting a 14-year-old girl and sexually assaulting a 16-year-old decades ago.

The raft of allegations of abusive conduct by powerful men in politics, business, news and entertainment — President Trump among them — has put pressure on Congress to improve its system for punishing misconduct in its own ranks.

The swift downfalls of NBC anchor Matt Lauer, comedian Louis C.K., actor Kevin Spacey and others in the private sector have highlighted the lumbering pace of the disciplinary process for Congress.

NBC fires ‘Today’ host Matt Lauer over ‘inappropriate sexual behavior’ »

Revelations of secret payments of taxpayer money to settle sexual harassment complaints against Conyers and possibly other lawmakers have sparked calls for more transparency.

Conyers and Moore have denied wrongdoing. Franken has apologized for his behavior, but said he did not recall some of what he’s accused of doing.

What are these secret settlements?

Over the last two decades, the congressional Office of Compliance has approved $17 million in settlements and awards for workplace complaints, including sexual harassment cases. All told, 264 complaints have led to payouts.

Congress has kept the details confidential, so it’s unclear whose misconduct sparked complaints and what their nature was.

But BuzzFeed last week published documents showing that a woman who accused Conyers of firing her for rejecting his sexual advances filed a complaint with the Office of Compliance. It ended with a confidential settlement of more than $27,000 in payments from his office budget.

What is the Office of Compliance?

It was created under the Congressional Accountability Act, a 1995 law passed in the aftermath of the Bob Packwood sexual harassment scandal.

The Republican senator from Oregon resigned in 1995 to avoid almost certain expulsion for abusing his power over women who worked for him, or who did business with his office. Among other things, he was found to have grabbed women and kissed them against their will.

The Office of Compliance is supposed to function as a sort of human resources department for Congress, enforcing labor rules similar to those that apply to the executive branch and businesses.

How does it handle sexual harassment complaints against lawmakers?

The opaque process starts with months of counseling and mediation. If the dispute is unresolved, the person reporting harassment can request an administrative hearing or file a federal lawsuit.

How well has this system worked for people sexually harassed by lawmakers?

The secrecy of the process makes it impossible to answer. But nonpartisan ethics groups say it’s ineffective, because those who report sexual harassment are left vulnerable to retaliation for speaking out.

“The blood measure in politics is loyalty,” said Meredith McGehee, the executive director at Issue One, a group that promotes government ethics and accountability. “That is the ultimate disloyal act, and you’re not trusted by anyone else after that.”

Isn’t there a long history of sexual misconduct by members of Congress?

Yes. Anthony Weiner, the New York Democratic congressman who exchanged lewd photos online with women and girls, resigned from the House in 2011 after admitting that his weeks of denials about sexting were false.

After stepping down, he continued sexting under the alias Carlos Danger, in some cases with a 15-year-old girl. On Nov. 6, he started serving a 21-month prison sentence for transferring obscene material to a minor.

Republican Rep. Mark Foley of Florida resigned in 2006 after news broke that he exchanged sexually graphic messages with underage congressional pages. The House Ethics Committee later found House GOP leaders were negligent and “willfully ignorant” of Foley’s wrongdoing, but recommended no punishment.

Former Republican Sen. David Vitter of Louisiana conceded he was guilty of “very serious sin” after his use of a prostitution service was revealed in 2007, but the Senate Ethics Committee declined to pursue the case.

GOP leader Mitch McConnell, then chairman of the Senate Ethics Committee, said its jurisdiction over Vitter’s conduct was questionable because he was not a member of Congress when it occurred.

McConnell has applied a different standard to the Franken case, saying the Ethics Committee should indeed investigate alleged groping by the Minnesota senator that took place years before his election to the Senate.

Over the last decade, the Senate Ethics Committee, nicknamed “the black hole” by critics, has sanctioned zero senators. The House Ethics Committee has fined two members for financial transgressions, but none for sexual misconduct.

Each committee has the discretion to investigate sexual harassment cases, regardless of any action at the Office of Compliance. Neither committee is known for speedy work.

Can Congress investigate sexual assault allegations against Trump?

A wide array of congressional committees conduct oversight hearings on presidential administrations.

But an investigation of Trump’s personal conduct in the years before he took office — more than a dozen women have accused him of sexually inappropriate behavior ranging from voyeurism to assault — would likely fall under impeachment proceedings for alleged “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The Republicans who control Congress have shown no interest in impeaching Trump.

Is anyone trying to change the system?

Rep. Jackie Speier, a Democrat from the Bay Area, has won GOP support for her bill to overhaul the system for reporting and punishing sexual harassment by members of Congress, but its fate remains unclear. It would end forced mediation and require more transparency on the handling of complaints.

“Zero tolerance,” she said, “is meaningless unless it is backed up with enforcement and accountability.”

ALSO

Will Trump ever have to answer to the women who say he harassed and assaulted them?

Sexual harassment hearings come as California Capitol is roiled by accusations and a resignation

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.