Confederate monuments are tributes to a whitewashed history

RICHMOND, Va. — Monument Avenue is a broad boulevard that stretches through some of the finer real estate in this city. At several intersections, the streets carve central squares and circles and at the center of those stand monuments to the venerated heroes of the Confederacy, monuments that some people would like to sweep into the trash heap of history.

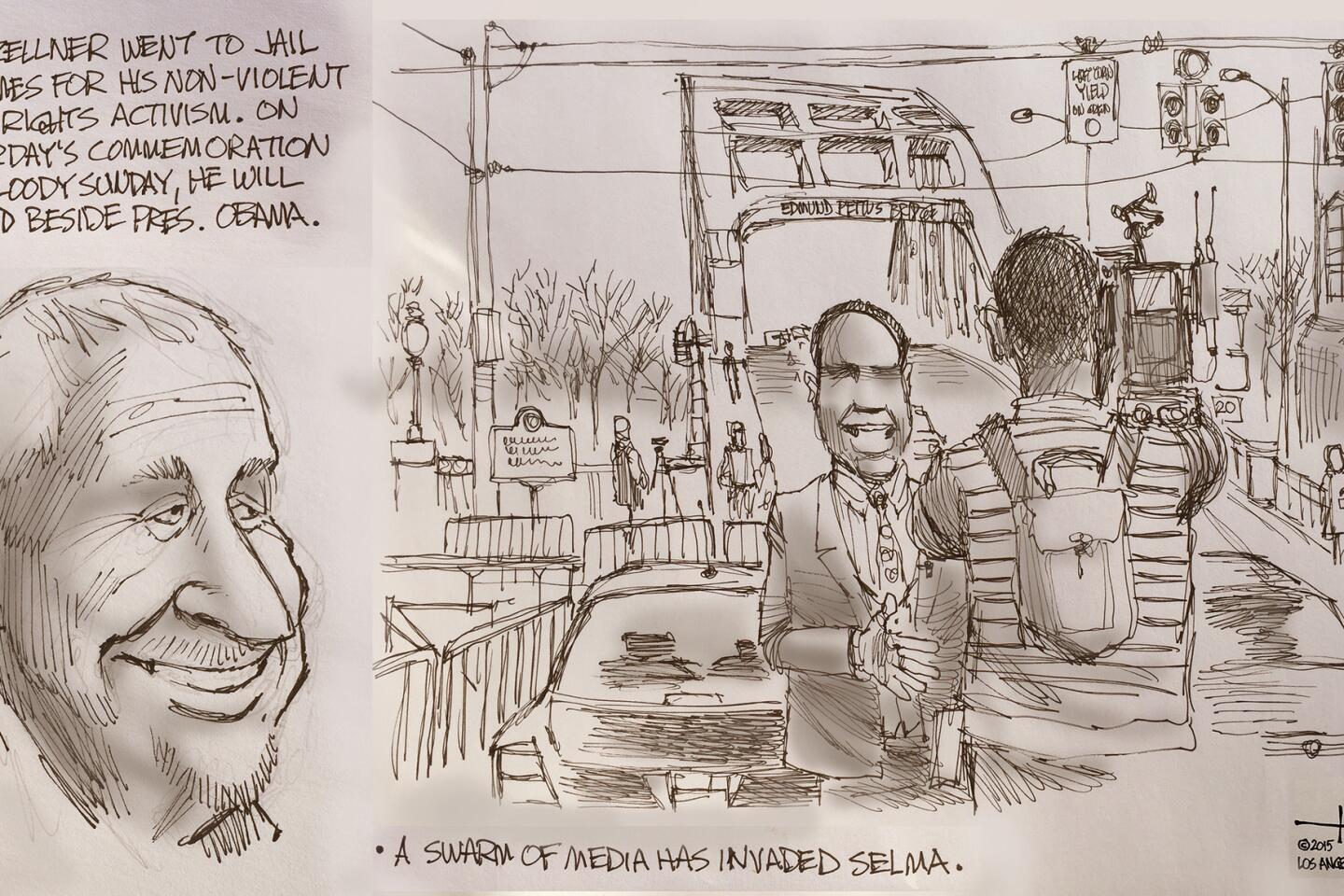

Like many American cities and towns, Richmond is confounded by what to do with these relics of another age and a commission has been set up to sort it out. This having been the capital of the Confederate States of America, what they do here may have more significance than in any other locale. Several days ago, I was on a bus with 17 other Project Pilgrimage participants from the West Coast, rolling along Monument Avenue for a rendezvous with some participants in the debate. We met up with a city councilman, Chuck Richardson, and a professor of history from the University of Richmond, Dr. Julian Hayter, who is a member of the monuments commission. Both are African Americans

The first monument we encountered was dedicated to Arthur Ashe, the black tennis champion and civil rights activist — obviously not one of the Confederate heroes. After a lot of effort and antagonism, Richardson succeeded in getting this statue put up as something of a rebuttal to the bronze images further along the avenue. And rebuttal would be the right term because the other statues were very much intended as an unambiguous statement in the segregationist era in which they were erected: The Southern cause was just and righteous, and this city will not apologize or relent.

A few blocks after Ashe stands a big equestrian statue of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson defiantly facing north. Beyond Jackson is an elaborate memorial to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. On the memorial’s stone steps sat five protesters who do not at all like the idea of removing the monuments. Flanked on his right by two wary white men and on his left by two equally suspicious white women, a lone black man greeted our group with a smile. He stood up, introduced himself as retired Army Sgt. Maj. James S. Haynes, Jr., and gave us a lengthy explanation of why he believes money spent on removing the monuments would be a waste since the city has “many fish to fry besides dead men on dead horses.”

The councilman, Richardson, sat nearby, fuming as Haynes spoke. Finally, he could not take any more and went on a tirade about the Confederate president’s white supremacist beliefs. One of the women shot back at him, telling Richardson to “get off the Democrats’ plantation!” She declared that it was the Democrats who were for slavery, which, while partially accurate in a historical context, ignores the reality that segregationist Democrats jumped to the Republican side in the 1960s and ‘70s.

One of the black students in the pilgrimage group got into a discussion with one of the white men. The man argued that, in assessing old Jeff Davis, “you’ve got to look at it from a 19th-century perspective.” The student stayed polite, but, walking beside me afterward, he wished he had reminded the man how that “perspective” would not have been healthy for a black man alive back in Davis’ day. Coming up behind, Richardson shook off his anger and said with a grin, “But you gotta love the artwork, I tell you.”

That artistry is undeniable and reaches epic proportions in the towering figure of Gen. Robert E. Lee astride his horse, Traveler, standing proudly atop a massive pedestal. Hayter noted that the huge traffic circle on which Lee stands is state property and that, in 1977 after a black majority took over the Richmond City Council, the Virginia Assembly quickly passed a law prohibiting the statue’s removal.

That same year, the Assembly approved a law that blocked the black-run city from expanding into the white-controlled outlying areas. Now, Richmond is ringed by white suburbs with good schools, while only 17 of the city’s 44 predominantly black public schools have accreditation. That sort of politically engineered disparity is just one of the myriad examples of how the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow still haunts the South. Those who want the monuments taken down say the statues are symbols and celebrations of that dark legacy, not mere tributes to ancestors.

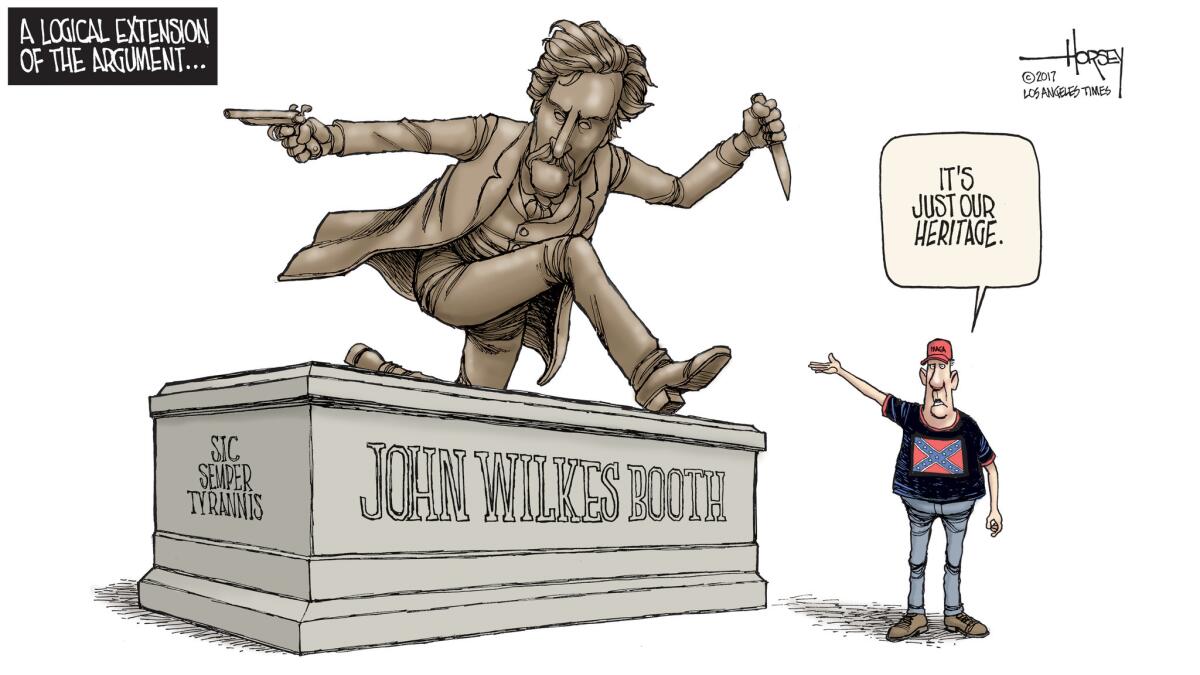

Hayter is in complete agreement with that view of what the monuments represent, but he notes that, when Baltimore and New Orleans took down their Confederate statues, it did not really change anything for the black residents of those cities. Hayter is open to the idea of doing something different in Richmond. Perhaps, signs and structures can be placed around or beneath the statues of Lee, Davis, Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart, the final rebel hero represented on the avenue, that will alter the message and teach a very different story.

Remarkably, by state mandate, Virginia’s schoolchildren are still being told that the Civil War was not a result of slavery, but was a dispute over state’s rights and preservation of Southern heritage — a noble Lost Cause that their white ancestors defended with blood and courage. Could the monuments be transformed into places that counter those erroneous lessons? There is a very different and far more accurate narrative to be told. As the founding documents of the Confederacy state very clearly, the Civil War was all about slavery and the Southerners who fought and died so bravely sacrificed for an unworthy cause.

There are 75 million descendants of Confederate veterans alive today, Hayter said, and a great many of them are not eager to admit their ancestors were on the wrong side. Nevertheless, the professor told me, “We are going to have to be honest with our history, or we will live and die by it.”

This is part two of a five-part series.

Tomorrow: Charlottesville.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.