Op-Ed: Recounts should be the norm, not the exception

- Share via

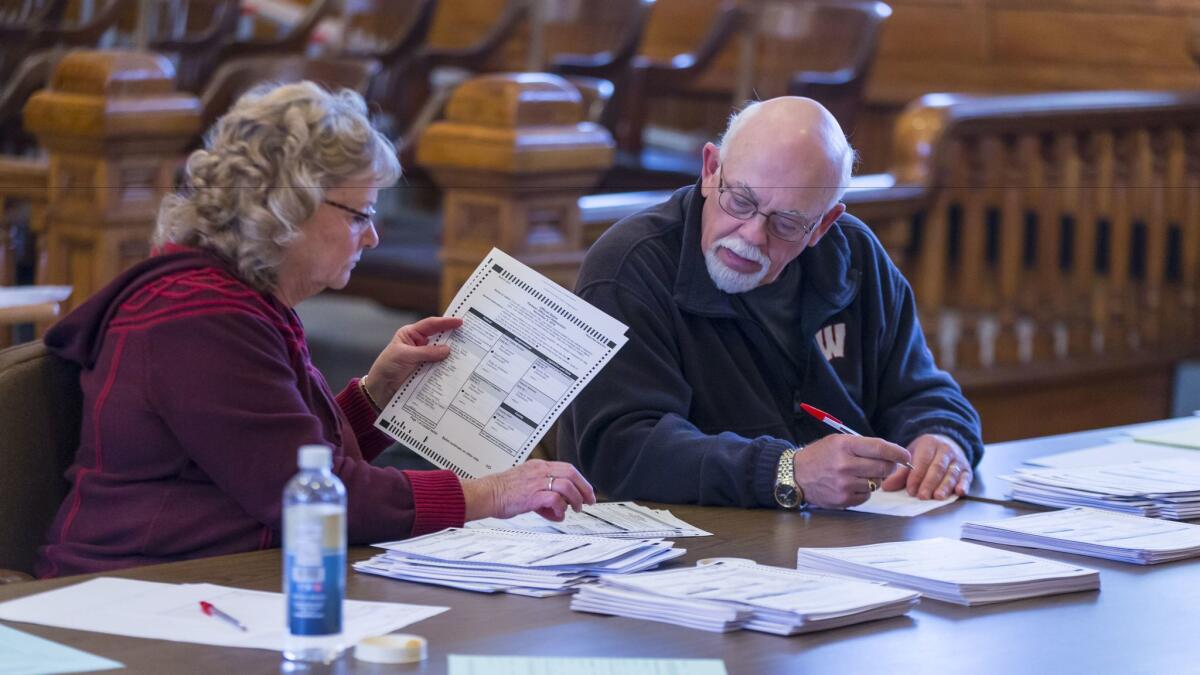

Jill Stein, her supporters and a group of experts struggled mightily to get proper recounts in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan. They were accused of paranoia and of simply wasting time.

Why is it so difficult, and so controversial, to get the results of a U.S. presidential election inspected and verified? Audits should be mandatory in all states; in fact, they’re part of the foundation of a healthy democracy.

Recounts not only are important for finding proof that voting machines were misconfigured or hacked. In a meaningful recount, evidence representing the voter’s intent is compared against the published vote totals. Even if a recount proves that everything went as intended, it’s a way to reassure the public — especially the losing side — that the announced winner of the election is legitimate.

A recount is comparable to checking the receipt before leaving the local grocery store. Some check, some don’t, but overall, we all agree that the ability to check a receipt is worth the paper it is printed on.

What should be a straightforward quality assurance check on the election result seems impossible to get.

For that reason, in many European countries, recounts — called fine counts or second counts — are done automatically, immediately after election day. They are conducted manually by counting paper ballots and do not have to be ordered by a judge because of a suspicion that something went wrong. It’s common practice for election commissions to foot the bill. (In the U.S., Stein and her supporters had to raise millions of dollars.)

If U.S. officials were more willing to conduct audits, the next step would be standardizing the voting and recount process. Quality matters.

In Pennsylvania for instance, 83% of the votes were cast and recorded on paperless voting machines, producing effectively no reliable record that could be used during a manual recount. This means that the only thing a recount can really prove is the absence of evidence of malfeasance.

Also in Louisiana, Georgia, South Carolina, Delaware and New Jersey, you’ll find voting machines that do not produce paper trails. Some are more secure than others. Some are easier to hack than others. But the point is that in these five states, voters never can be sure that their votes were recorded as intended. Hence, the acceptance of the final results requires a leap of faith, a blind trust in essentially untrustworthy machinery, during a period in history when anyone can easily Google “how to hack a voting machine” and find online tutorials with very specific instructions.

Of course, even the states that do have the ability to easily conduct a proper fine count don’t bother. In Maryland, for example, voters mark their ballot papers and scan them with optical scan machines. Yet no one inspects the paper ballots independently of the scanner.

Recounts would give Americans something other than official assurances that the election systems are secure. Mistakes happen, intended or unintended. Even the best of IT systems may contain bugs or be otherwise vulnerable.

Following the media coverage of Stein’s rally outside Trump Tower in Manhattan, one wonders what it would take to convince politicians, lawmakers and election officials of the importance of accountability in the electoral process.

The U.S. lags behind Argentina, Chile and Jamaica on the international electoral integrity index conducted by the University of Sydney’s Electoral Integrity Project. The federal court ruling halting the recount in Michigan illustrates why; what should be a straightforward quality assurance check on the election result seems impossible to get.

Mandatory recounts, financed by public money and integrated into the electoral process, would certainly be a big step forward in improving America’s integrity rating. But first the country needs to require voting machines that leave a paper trail.

Such efforts would increase trust in the electoral process not only among Americans but also among the billions of world citizens whose future also is affected by the outcome of the U.S. election.

Carsten Schürmann is an associate professor and election technology expert. Jari Kickbusch is a journalist and author. Both work at the IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and observed the election in Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.