The mailbox-driven campaign: How California political races captured voters’ attention and frustration in 2016

- Share via

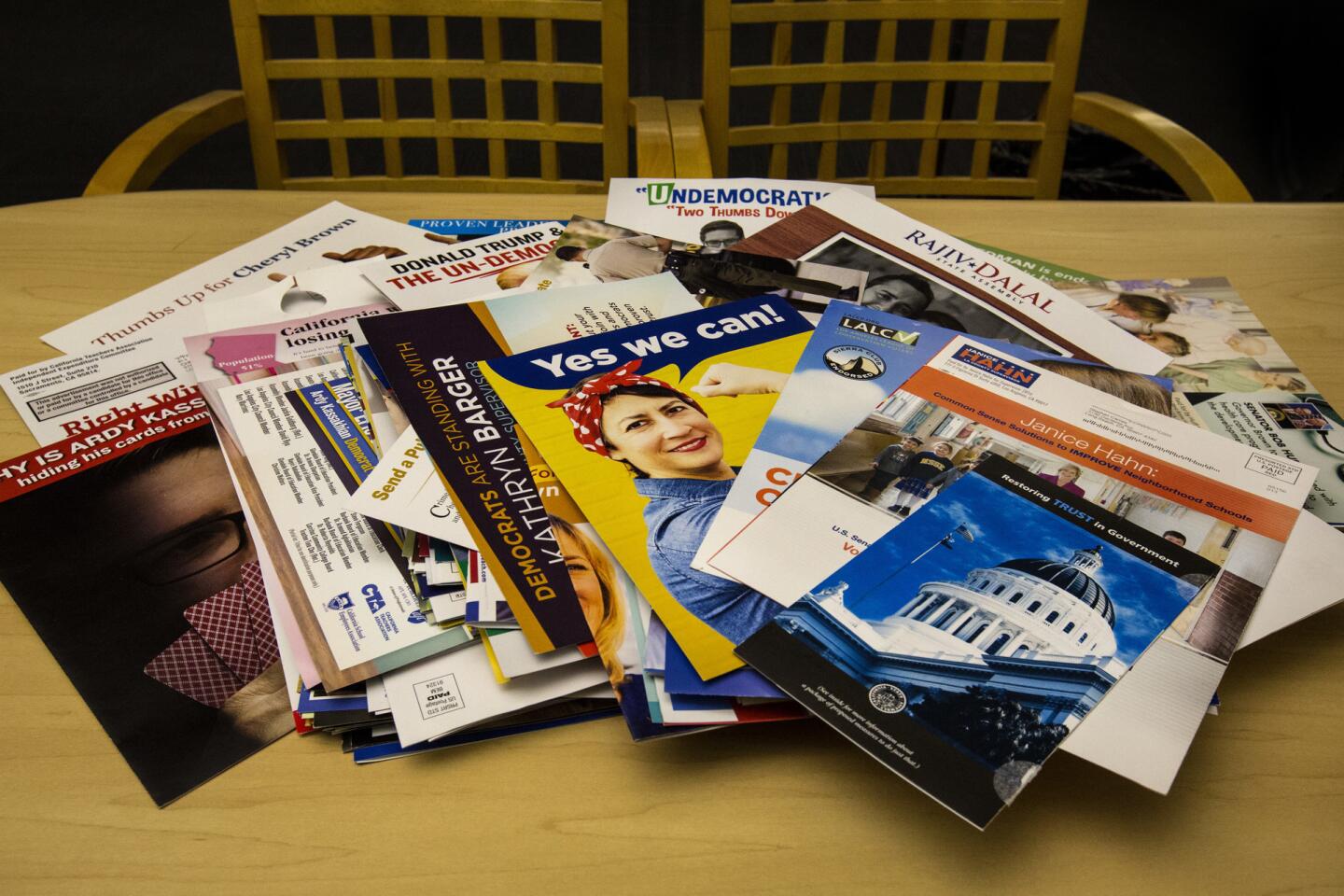

For Californians, prying an inches-thick stack of political ads from a mail slot is a familiar-but-vexing ritual, a routine repeated every 24 hours in the waning days of an election cycle. And for those new to the state who arrive in an election year, their initiation into the tradition seems to begin in earnest just as boxes are unpacked, as campaigns of all sizes and stripes vie for their attention.

While rifling through — and disposing of — political mailers can represent little more than a daily inconvenience, in some races, particularly down-ballot match-ups, these ads are often the primary way a campaign communicates with voters. When it comes to articulating their stances on the issues, candidates without the benefit of the national stage may struggle to get the word out about their campaigns and turn to direct mail to do the job.

But it can backfire and turn off voters, said Peggy Scholz, a Pasadena registered nurse who was among several readers who contacted The Times about the flood of ads they received. The Times put out a call to readers, asking them to send in photos of mailers sent to them during the primary or general election.

“We are not opposed to a few modest mailers that present a candidate’s positions —although their websites are better for that and cost less — but this particular election went a little bit overboard,” Scholz said. “We hope to see a better display of fiscal responsibility in future campaigns.”

Here are some highlights from 2016’s political mailers:

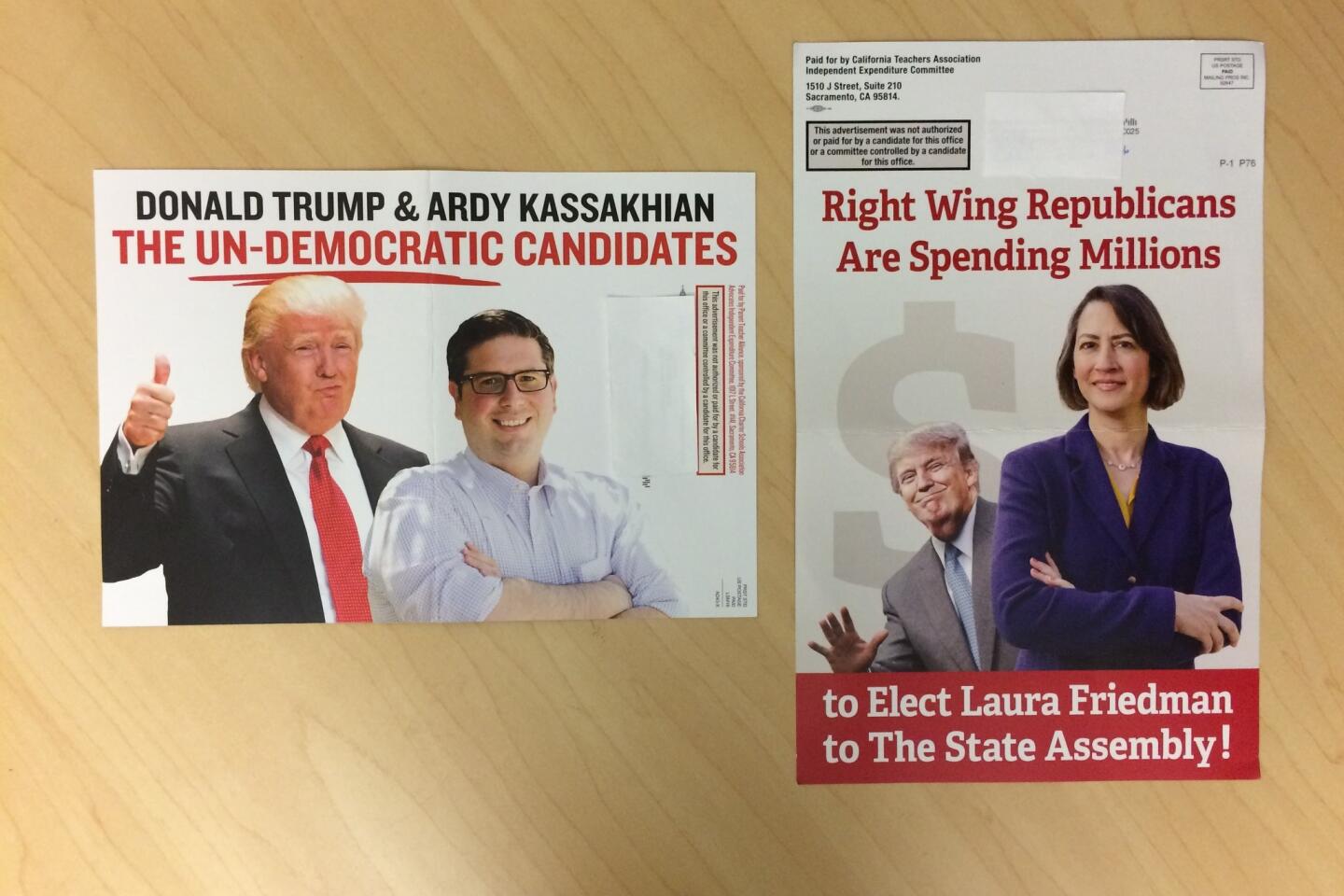

1. Trump as bogeyman: The Republican presidential nominee pops up in California’s down-ballot races

For some Democratic candidates in California, a key strategy was mentioning Donald Trump’s name almost as often as their own. It’s no surprise the Republican presidential nominee popped up in so many down-ticket races he had nothing to do with: According to a USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times poll released Sunday, 69% of Californians held an unfavorable view of Trump, with 61% holding a very unfavorable view.

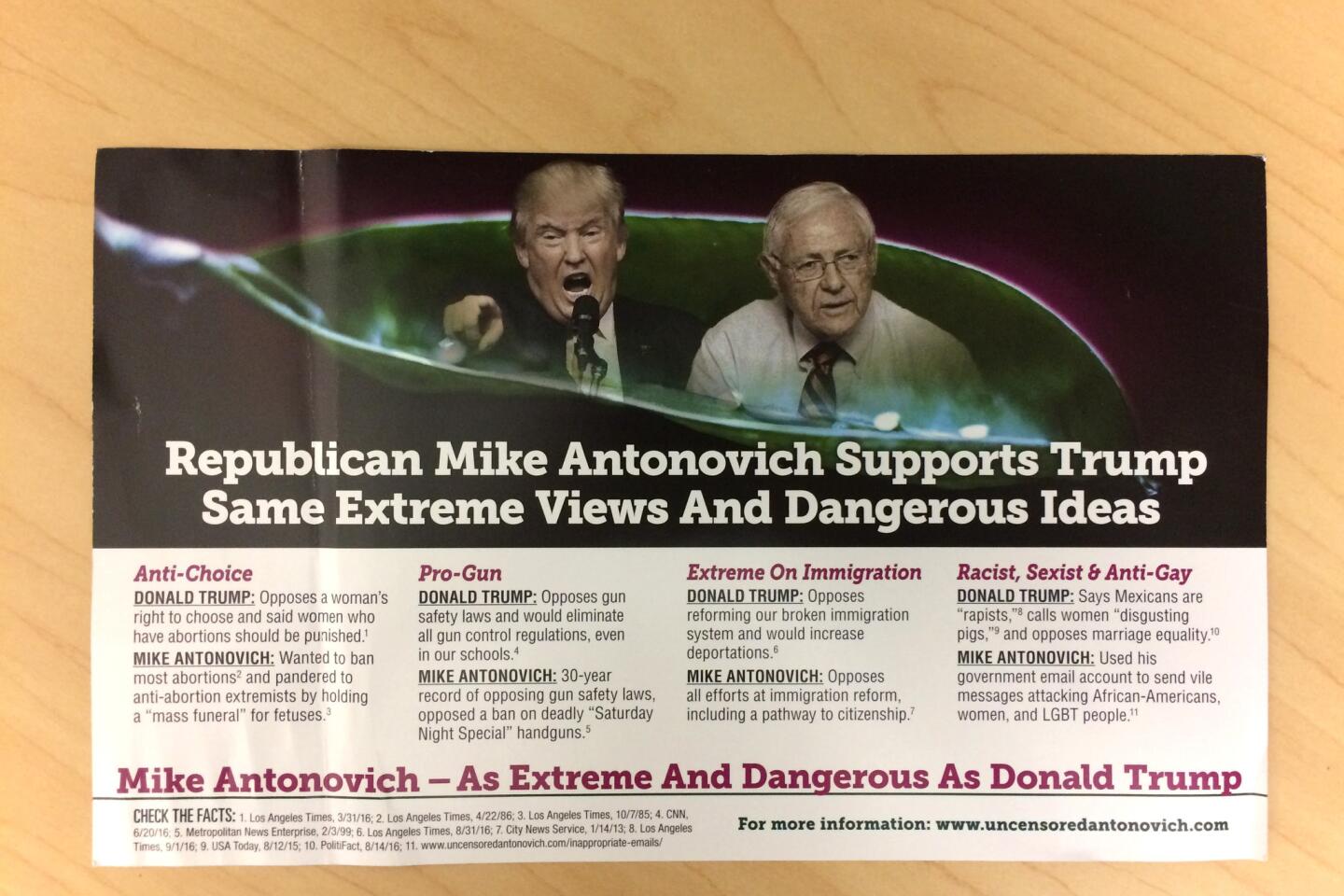

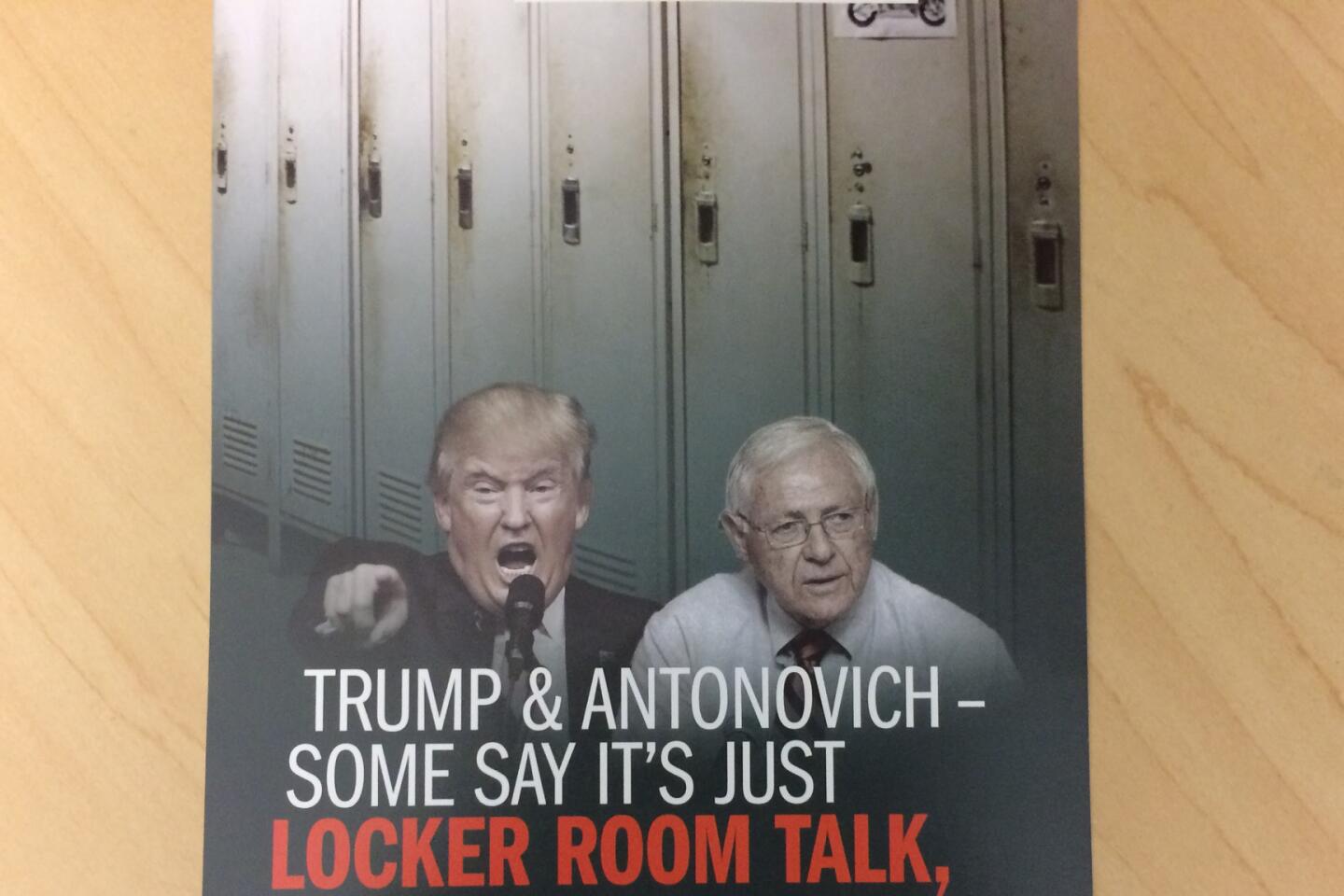

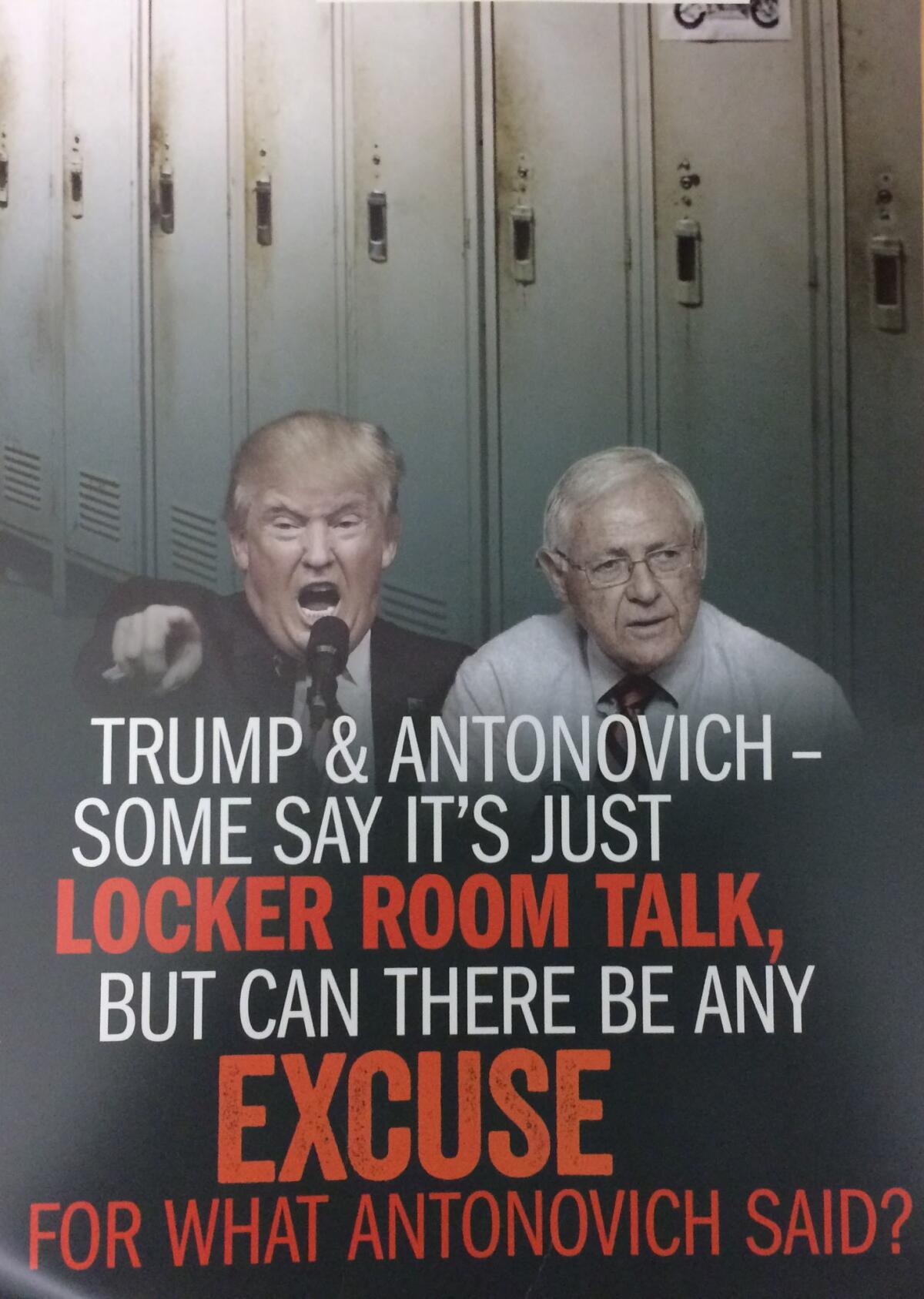

In the competitive state Senate race between Democrat Anthony Portantino and Republican Mike Antonovich, Portantino’s campaign sent out a deluge of mail trying to tie his opponent to Trump.

One claimed Antonovich is “as extreme and dangerous as Donald Trump,” and included a photo illustration of the men as “two peas in a pod.” Other mailers showed Trump and Antonovich’s photos against a backdrop of grimy lockers, accusing them of “locker room talk” and skewering Antonovich’s “sexist and racist statements” over the years.

Assembly Democrats also tried to play up the “Trump effect” in swing seats. Abigail Medina, a Democrat hoping to unseat Assemblyman Marc Steinorth (R-Rancho Cucamonga), declared her rival and Trump were “two sides of the same coin.”

“What’s the difference between Dante Acosta and Donald Trump?” asked a mailer sent out by Acosta’s opponent for Assembly District 38, Christy Smith. “NOTHING,” was the reply, with claims that both Republicans “tied themselves to right-wing extremists” and have been “accused of financial misconduct.”

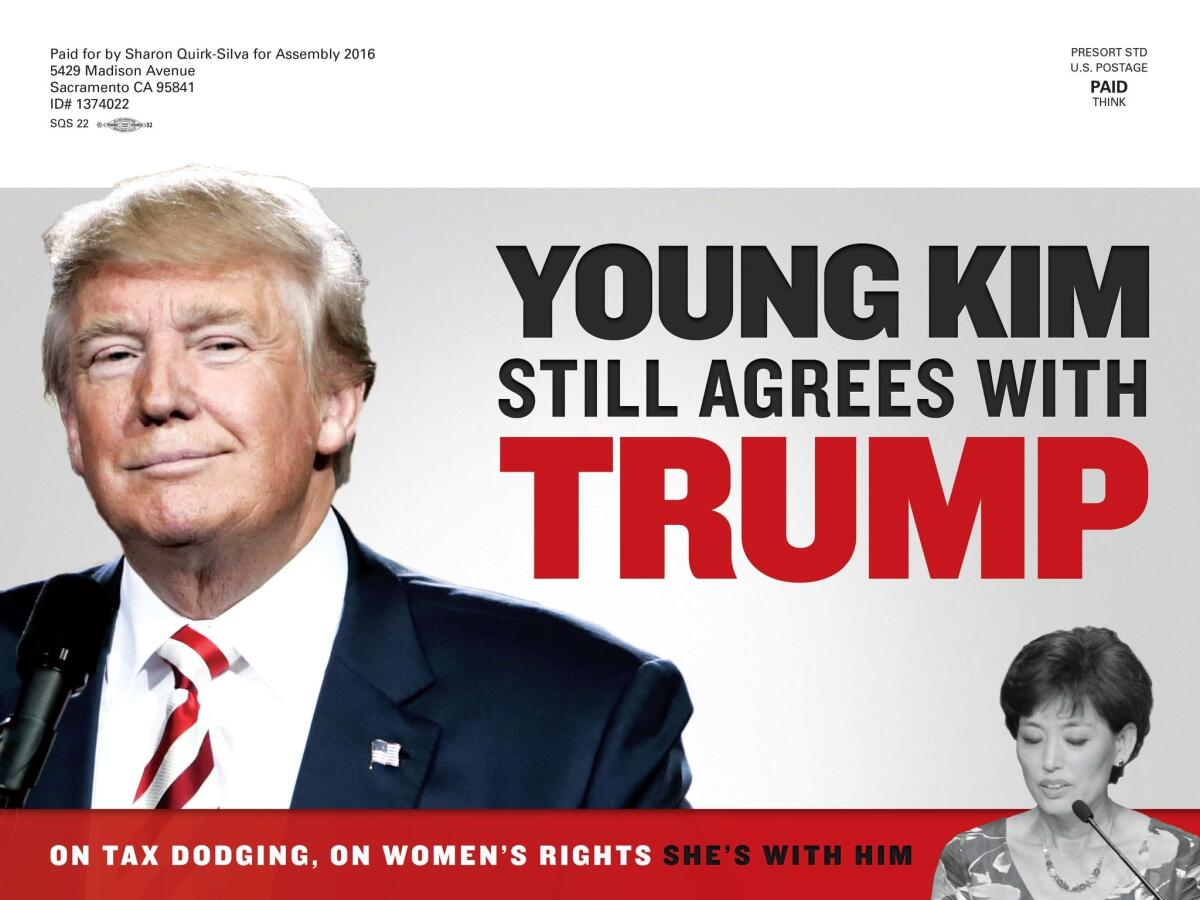

The campaign of Sharon Quirk-Silva, who has raised more than $4.3 million in her effort to recapture a seat she lost to Republican Young Kim in 2014, is another example of Trump’s ubiquity in California races.

Quirk-Silva’s campaign made Trump such a central part of its attack ads and mailers against Assemblywoman Young Kim (R-Fullerton) that it registered itself with the Federal Election Commission as an independent expenditure committee spending against Trump.

2. Anti-death penalty group to voters: Don’t turn California into Texas

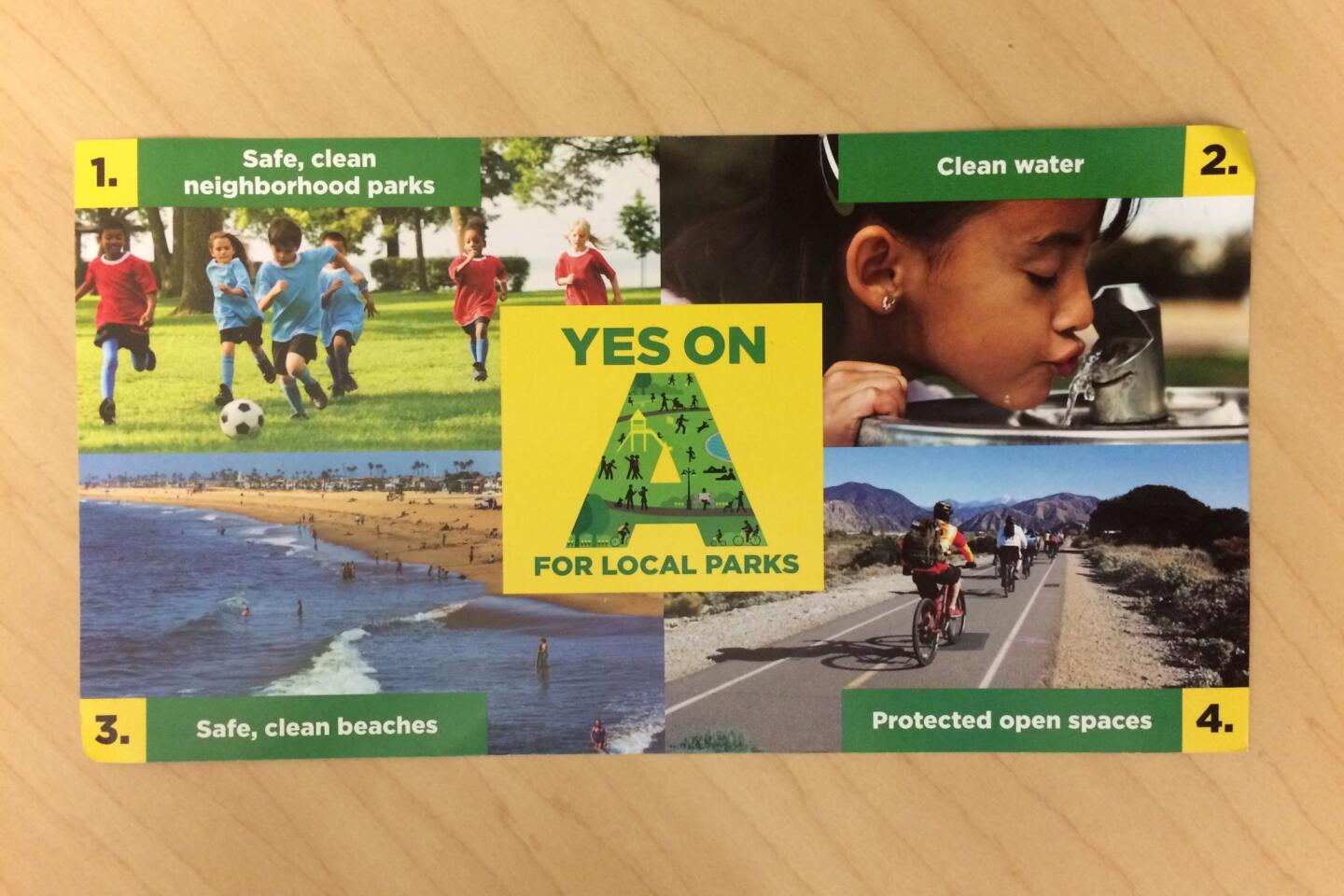

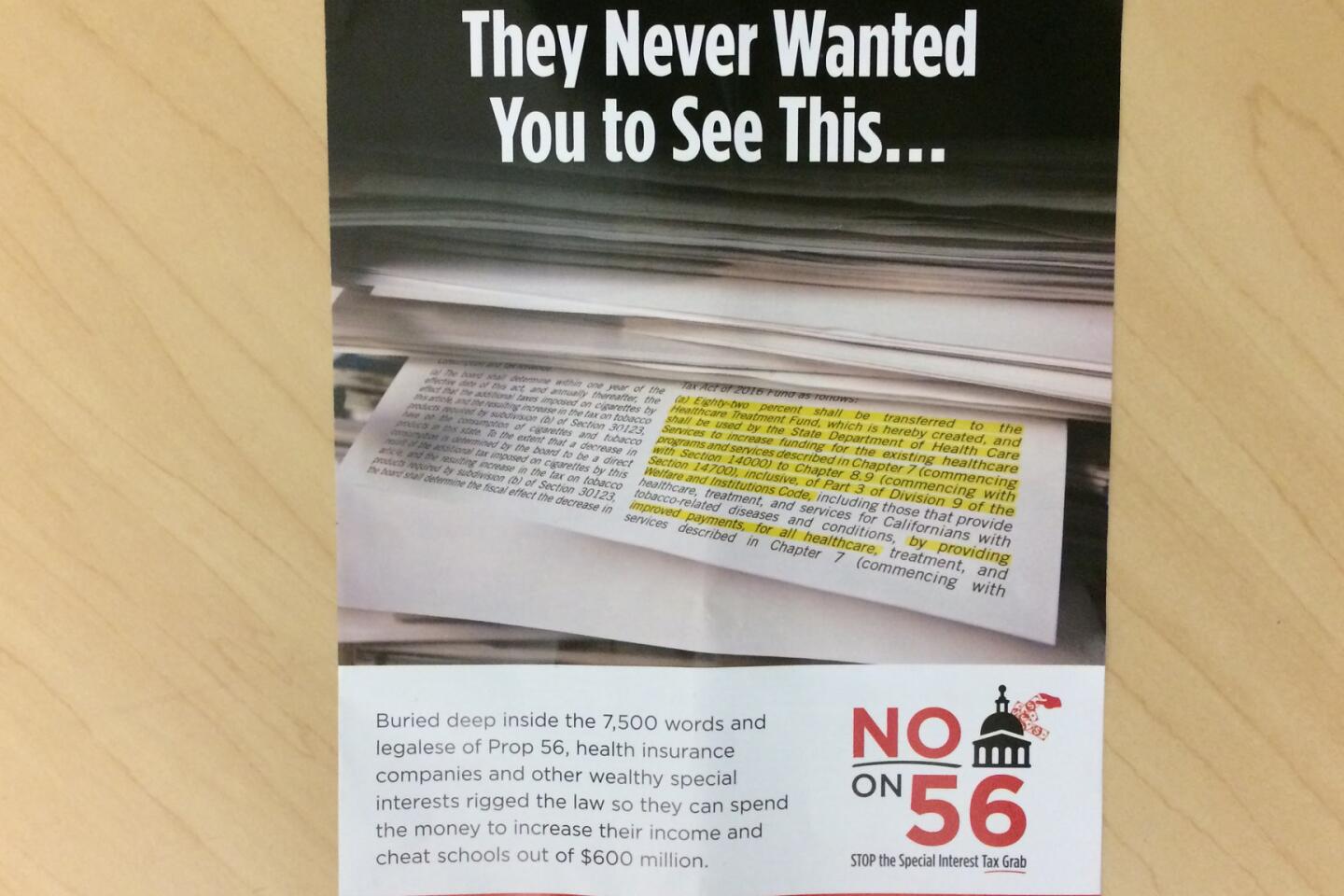

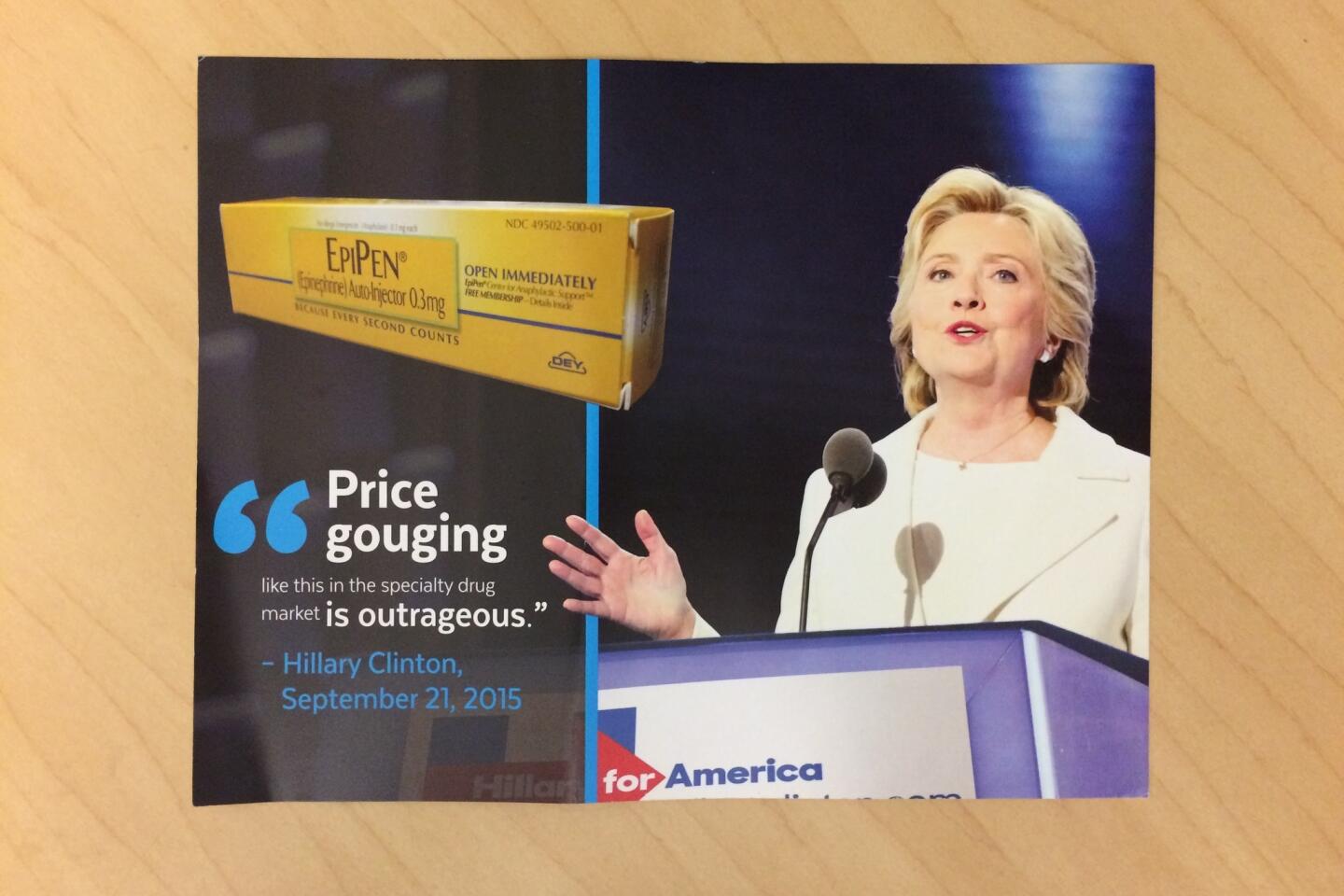

In California, ballot measures are big business. Money raised to support or oppose 17 statewide propositions alone has exceeded $470 million, with an average of $1.5 million raised each day.

Campaigns for and against ballot measures are typically waged through the mail — with the exception of press conferences, rallies, expensive television ad buys and the odd debate — and bank on claims made in bold-face lettering alongside splashy graphics to grab a voter’s attention.

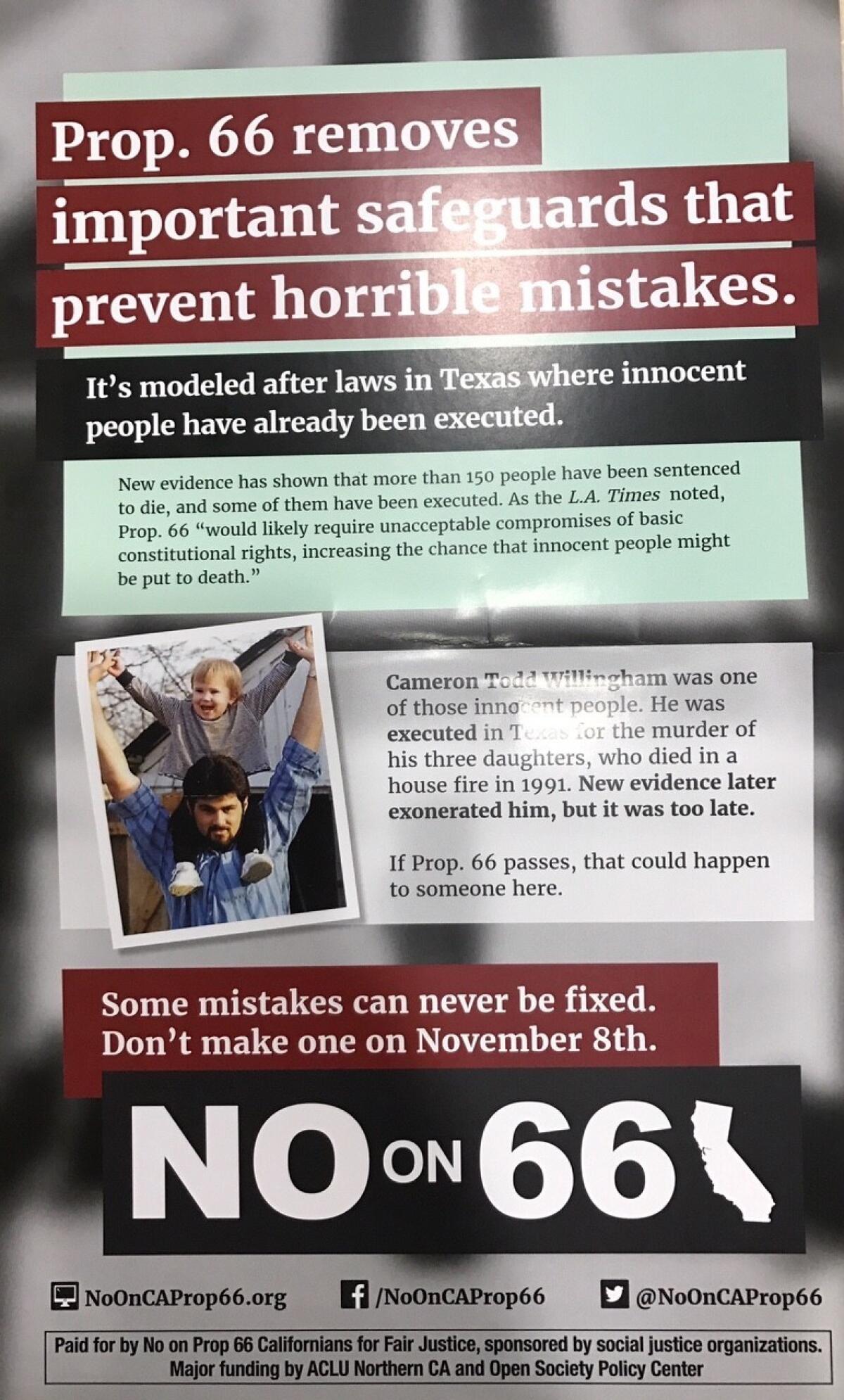

The campaign against Proposition 66, which would speed up the death penalty process in the state, looked outside California to make its point. It argued the ballot measure is “modeled after laws in Texas where innocent people have already been executed,” a claim the proposition’s author, Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, says is false.

“There is not one section, not one paragraph, not one sentence in these provisions that is modeled on anything in the law of Texas,” Scheidegger said.

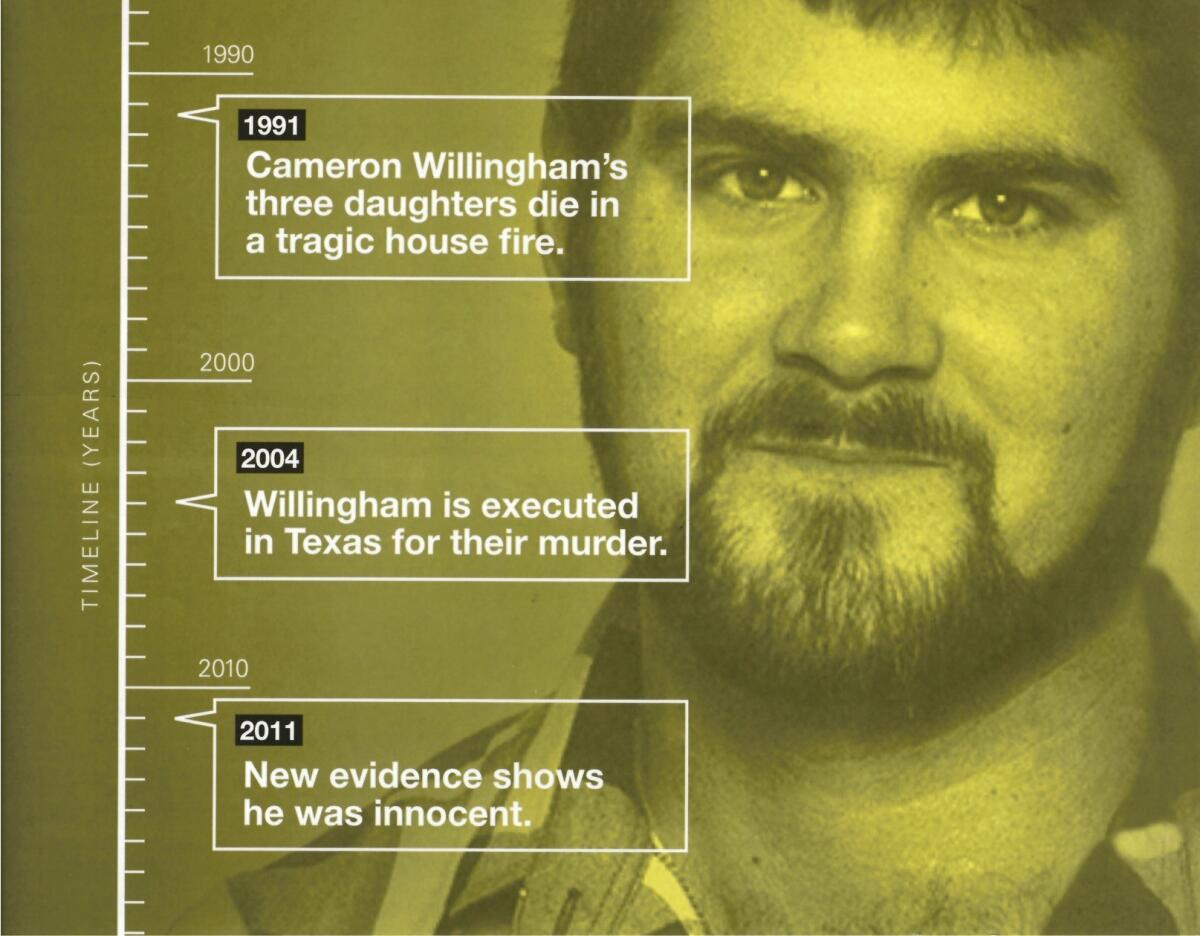

The group Californians for Fair Justice used its campaign mailers to tell voters about the case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was convicted of intentionally starting a 1991 fire in his Corsicana, Texas, home that resulted in the deaths of his three young daughters. He was sentenced to death.

Willingham’s attorneys released findings from a fire investigator that cast doubt on his guilt, and he sought and was denied a reprieve from then-Gov. Rick Perry. He declared his innocence until he was put to death in 2004, after the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied a request to stay his execution.

After Willingham’s death, some scientists contended he could not have been guilty based upon what they said was faulty evidence. Others criticized Perry, saying he impeded justice by removing members of a state forensic science commission that in 2008 agreed to look into Willingham’s case at the urging of the Innocence Project.

Mailers for the “No on Prop. 66” campaign, which were funded in part by the ACLU of Northern California and the Open Society Policy Center, issued a warning to voters: “Cameron Todd Willingham was one of those innocent people… New evidence later exonerated him, but it was too late. If Prop. 66 passes, that could happen to someone here.” (Willingham was not legally exonerated or declared “actually innocent,” which can only be done by the state.)

Another mailer featuring a grid of photos of several exonerees was even more direct, saying, “Californians deserve better” than the laws in Texas.

“Some mistakes can never be fixed,” it read. “Don’t make one on Nov. 8.”

3. The snail-mail race for an open San Fernando Valley Assembly seat

To open a mailbox in the 43rd Assembly District this election cycle was to get a glimpse of the record-breaking $69.8 million in outside spending this year by groups hoping to influence legislative races across the state.

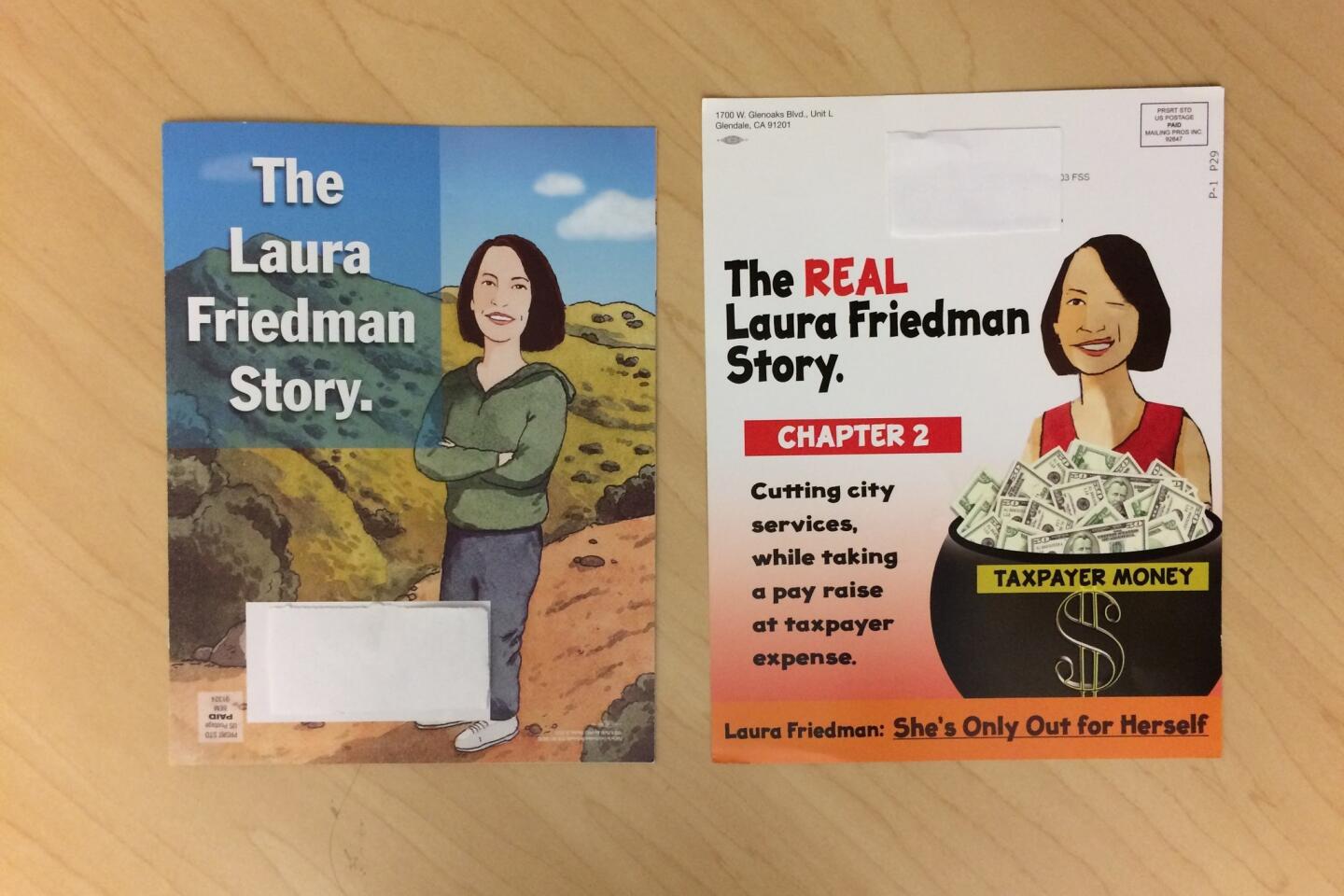

In this San Fernando Valley race, Glendale City Councilwoman Laura Friedman faces fellow Democrat and Glendale City Clerk Ardy Kassakhian, both of whom are well-funded and have powerful, deep-pocketed interest group backers.

Voters received dozens of pieces of mail from the two candidates and independent expenditure committees supporting them, sometimes getting as many as five mailers in a single day.

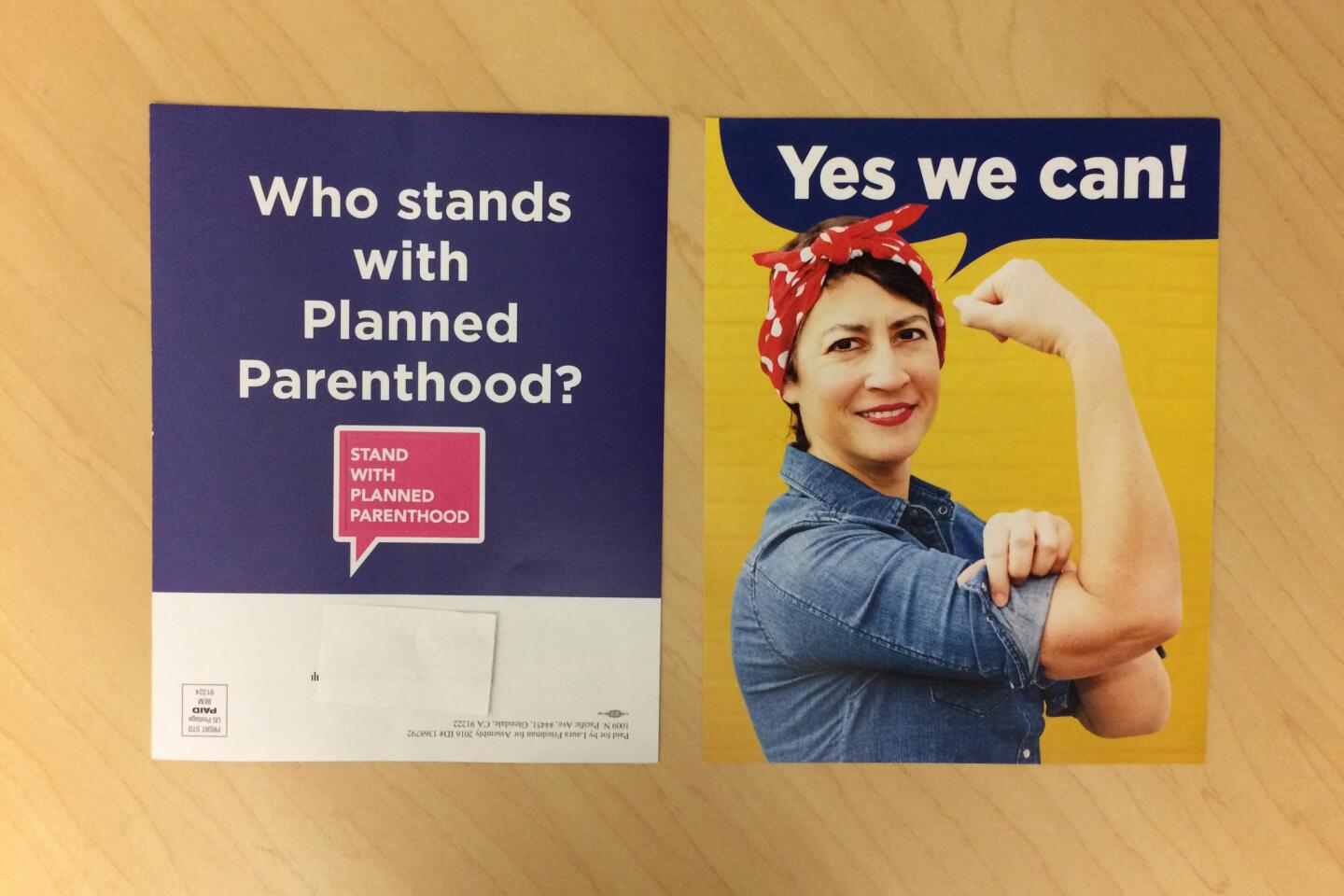

Friedman’s pieces mostly focused on her stance on gun control, her endorsements from Planned Parenthood and the need to elect more women to the Legislature (one featured her as Rosie the Riveter), while Kassakhian’s touted his endorsements from teachers and tried to disseminate the “real Laura Friedman story,” including her missed votes on the City Council.

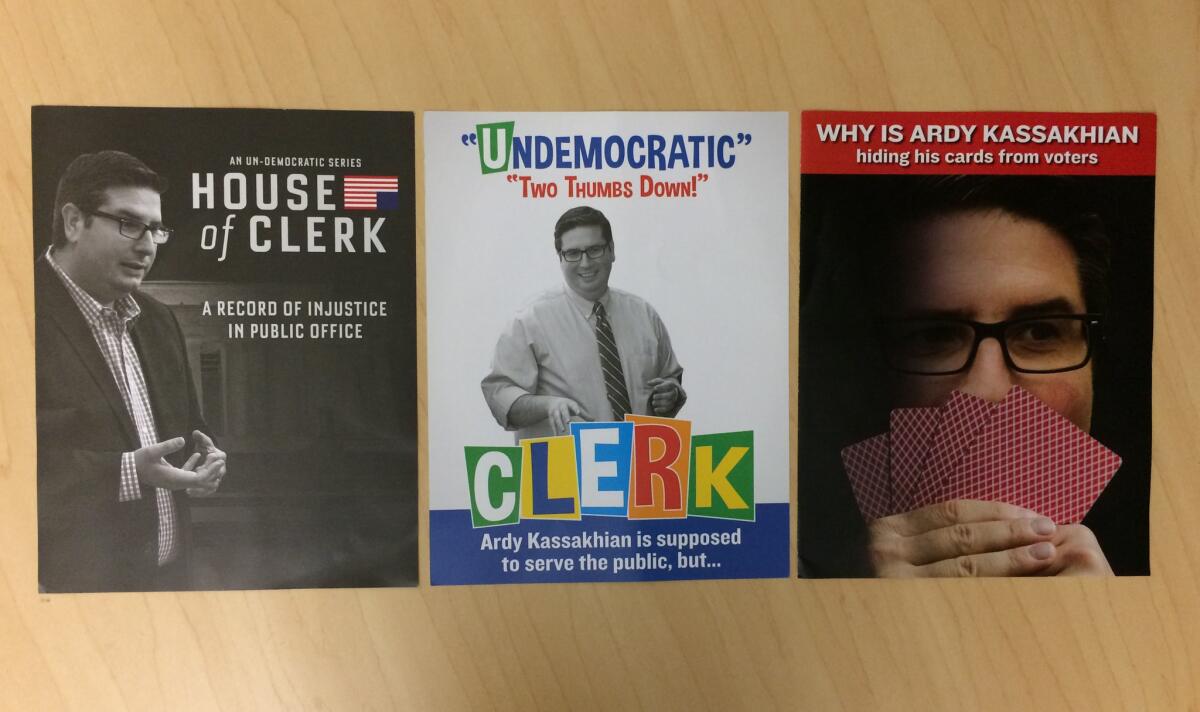

Some of the most memorable pieces came during the crowded primary season, when Kassakhian and Friedman were fighting to break through a field of eight candidates. The California Charter Schools Assn. advocacy group, through a group calling itself the Parent Teacher Alliance, spent $1.4 million in the primary and $1 million in the general election supporting Friedman and opposing Kassakhian. They bankrolled most of the negative mailers against him.

One mimicked the movie poster for the 1994 movie “Clerks,” calling Kassakhian “undemocratic” and claiming he’d shirked his duties as an elections official. Other pieces funded by the group played off the dark Netflix political series “House of Cards,” and superimposed Kassakhian’s face on playing cards saying he is a “risk we can’t afford.”

Independent expenditures supporting Kassakhian during the primary, paid for mostly by a PAC funded by the California Assn. of Realtors, emphasized his endorsement from Mayor Eric Garcetti and labeled him the progressive choice.

But in the general election independent expenditures for Kassakhian mostly dried up. The only prominent ad, a mailer about his stances on water conservation, was paid for by the California Chiropractic Assn., which spent $123,000.

Kassakhian has sent a few mail pieces out, both attacking Friedman and touting his endorsements. Other mail sent on Kassakhian’s behalf included pot-holders delivered to voters’ mailboxes from some of the state officials backing him, including state Treasurer John Chiang and state Senate leader Kevin de León.

Friedman and her backers continued the onslaught of mail in the final days of the general election cycle, touting her environmental record and endorsements and recycling a mailer that introduced voters to her biography with cartoons and stories about being raised by a single mother and becoming an entertainment industry executive.

Times staff writers Sophia Bollag and Jazmine Ulloa contributed to this report.

allison.wisk@latimes.com; christine.maiduc@latimes.com

Follow @allisonwisk and @cmaiduc on Twitter

ALSO

Track these contests live as results come in

Your guide to California’s 17 ballot measures

Will these Southern California Republicans keep their Assembly seats despite Trump?

Propositions on Tuesday's ballot have set a state record for donations

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.