For moms at a shrinking South L.A. school, the teachers’ strike is about survival

Angel Flores, 11, stayed out of school to join his family in support of the L.A. teachers on strike. (Claire Hannah Collins / Los Angeles Times)

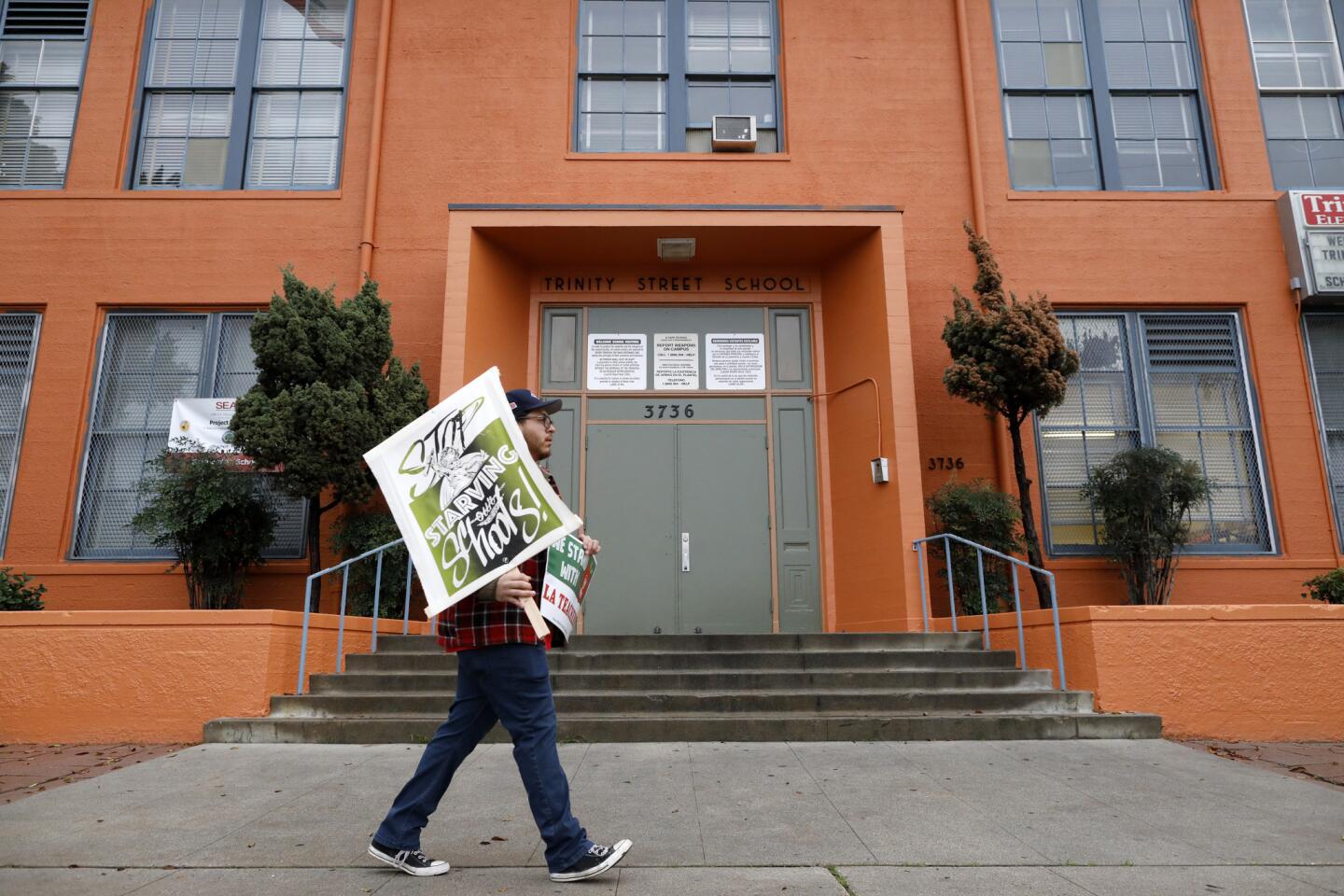

The last time teachers went on strike, back in 1989, Alejandra Delgadillo was a fifth-grader at Trinity Street Elementary School.

Her sons later attended the school in Historic South-Central too. The youngest moved on to middle school last year.

Still, Delgadillo this week was among the first to join the school’s picket line, and she arrived loaded with paper cups, juice, doughnuts, pretzels and a canopy to guard teachers from the rain.

“This school means so much to me,” she said. “It’s not about the old buildings. It’s about all the people who work so hard every day inside those buildings.”

Delgadillo, 39, is part of a small band of moms who look after Trinity and dedicated themselves in recent weeks to preparing the school community for the massive strike.

They are close to the teachers and support their demands. But their personal protest goes deeper. They say they are fighting for the school’s survival after years of decline and shrinkage — because in a school in a neighborhood like theirs in the Los Angeles Unified School District, you have to fight hard for anything you get.

It’s the sort of story you hear in many spots in the district, as enrollment declines and resources dwindle.

Delgadillo, a retail manager, has seen it all from her cream-colored, stucco home of more than 30 years, right across the street from the school.

When she was a student in the 1980s, Trinity was a bustling neighborhood school with more than 1,500 students.

Today, it has no more kindergarten or first grade and only about 300 students.

So much of what Delgadillo cherished about her school is gone: the essay writing contests that helped her with her bashfulness; the classes in art, cooking and sewing; the drill team and assemblies at which everyone recited the Pledge of Allegiance and then “God Bless America” and “My Country ’Tis of Thee.”

“All these things made us feel proud and happy about our school,” she said.

When she stepped inside to enroll her eldest son, Ricardo, in 2007, she was glad to see familiar teachers and office staff, the friendly custodian Johnny.

But over the years, resources had dwindled. Programs went away. Teachers were laid off. Test scores dropped. Students left for other schools and other parts of town.

As time went on, the nearly entirely Latino neighborhood had more and more choices.

Within a 2½-square-mile radius, there are now nearly a dozen elementary schools. A third of them are charters.

One, Gabriella Charter School 2, opened just last year on the Trinity campus in an arrangement known as co-location that the teachers’ union dislikes.

Many parents fought to keep the new school from taking over more than half a dozen empty Trinity classrooms, but Proposition 39 gave them no leg to stand on. The ballot measure approved by state voters in 2000 dictates that school districts must provide empty space to charter schools.

“It’s like having a new roommate move in without your consent and now you have to share a bathroom and a bunch of other stuff all the time,” said fifth-grade teacher Jesus Torres. “It’s nothing personal, but it’s no fun.”

As buzz about the strike spread across Trinity’s campus, it was impossible to talk about teachers’ frustrations without bringing up Gabriella. Many parents and teachers believe the school is encroaching not only on their space and supplies but also on their future as a public school.

It’s a messy, bureaucratic struggle playing out across the city as an increasing number of public schools that were once central to the neighborhood are battling to hold on to students, said Tyrone Howard, professor of education at UCLA.

“We have to be careful,” he said. “Schools are supposed be beacons of hope, but if the public schools don’t have the resources, we’re going to see a widening of inequality in our city.”

District officials said parents enjoyed having choices and that many of the newer L.A. Unified schools nearby were necessary to alleviate overcrowding.

Trinity, once stacked with modular classrooms, has seen some improvements, said Eugene Hernandez, administrator of operations for Local District Central. It’s freshly painted and now has access to a grassy field, he said, and there’s a plan to fix the old fencing out front.

When asked about the frustrations many Trinity parents express, about their sense of having been left behind, Hernandez said: “It’s important for parents to stay informed. In retrospect, maybe we could have built stronger connections with parents and community leadership back then.”

For the group of moms at Trinity, it’s been an uphill battle to keep to their tiny school intact.

Though Trinity’s class sizes are small at 20 to 24 students, the school struggles with the most basic problems. It’s hard to get the district to deal with broken air conditioners or the mice feces that are found in the classrooms. Like other schools, Trinity also wants staff it doesn’t have: teaching assistants, counselors, a full-time nurse.

The moms try to help where they can, mostly by volunteering in the classroom.

A few years ago, Angelica Romero helped bring back Trinity’s dormant PTA.

She and Delgadillo and the others began raising money bit by bit, selling $1 chocolates and small bags of popcorn to the kids after school. On Valentine’s Day, kids donated $1 for cards for their moms.

It took them three years to amass close to $10,000.

“I was so proud of us,” said Romero, a stay-at-home mom who sells vitamins to make ends meet.

The women used the money on things they thought would bring joy to the kids. They hired a magician and brought in a traveling aquarium exhibit.

Today, the PTA account has about $800, though the group dissolved several years ago.

On Monday, Romero, whose son is in fifth grade, joined the teachers and other moms on the picket line. There she met up with Torres and Sonia Perez, a second-grade grade teacher who has been at Trinity 26 years.

Together, they raised Delgadillo’s canopy, set up a coffee station, waited for the others moms to arrive.

Fast-talking Kimberly Martinez arrived by foot pushing a stroller, with her three kids in tow.

Together, they’d handed out so many fliers, spoken to so many parents.

“We’re finally doing this,” Martinez said.

Romero laughed and told her, “We need you. You’re the megaphone of our group.”

Then the moms grabbed their signs and marched outside their school, chanting as loudly as they could, “We are the parents. The mighty, mighty parents.”

esmeralda.bermudez@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.