L.A. is working to count a hidden population — homeless young people

- Share via

When Marlon Sibrian turned 18 and aged out of the Los Angeles County foster care system, he had nowhere to go. His social worker dropped him off at the door of a Boyle Heights youth shelter.

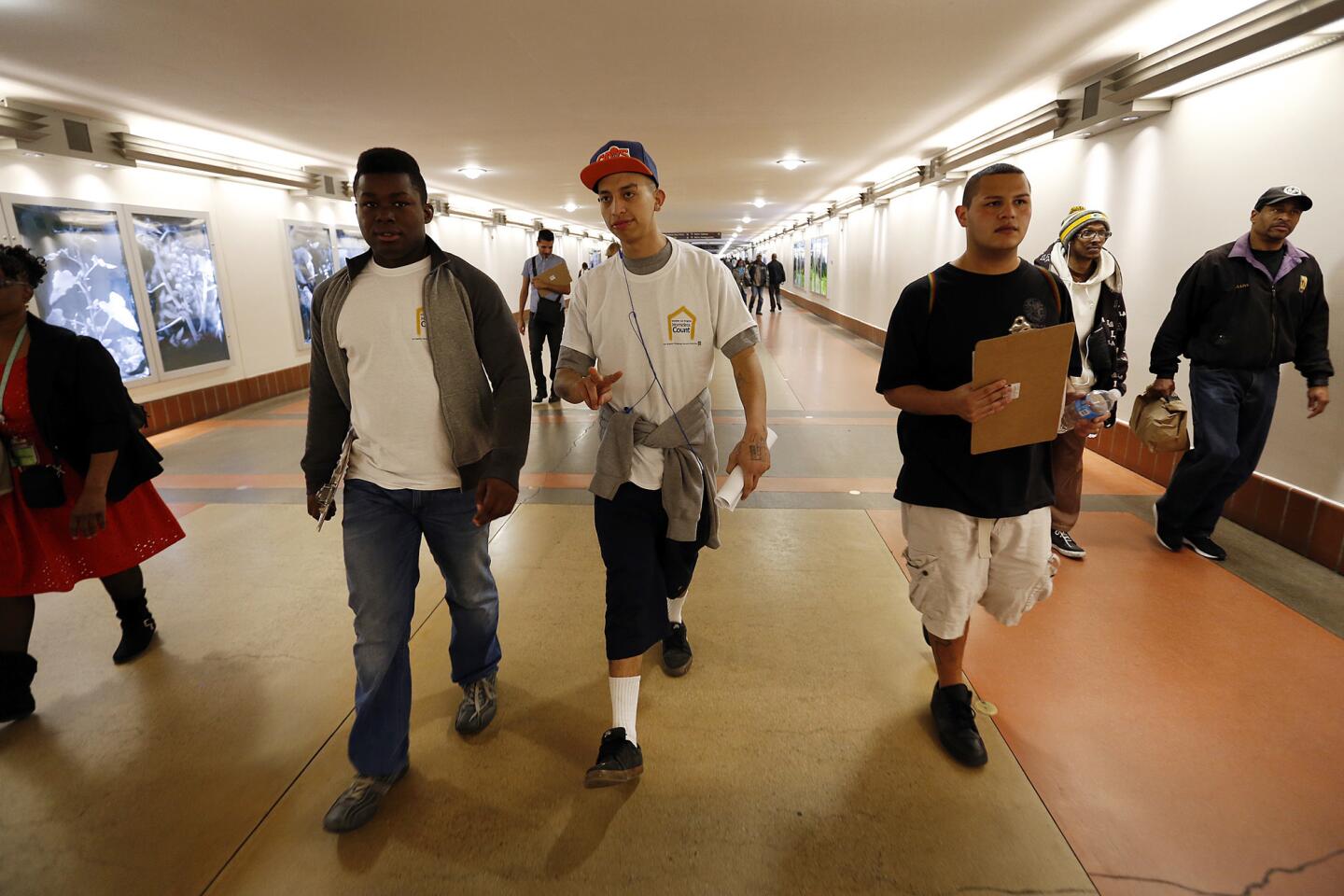

Sibrian’s time there made it easy for him to recognize the homeless young men amid similarly hoodie-clad and beanie-topped individuals at Union Station.

“Hey, bro,” Sibrian, 21, said, slapping a young man’s hand.

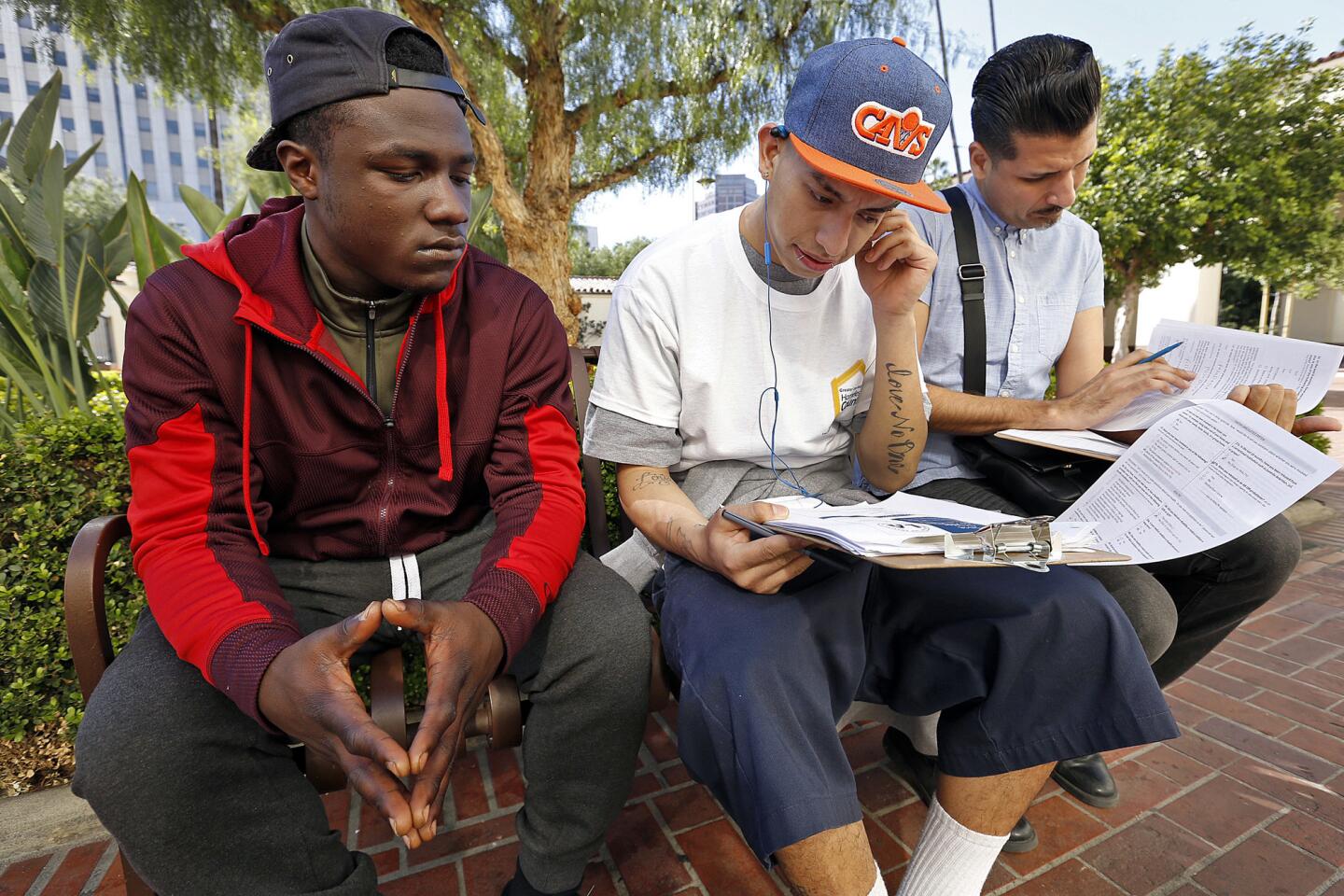

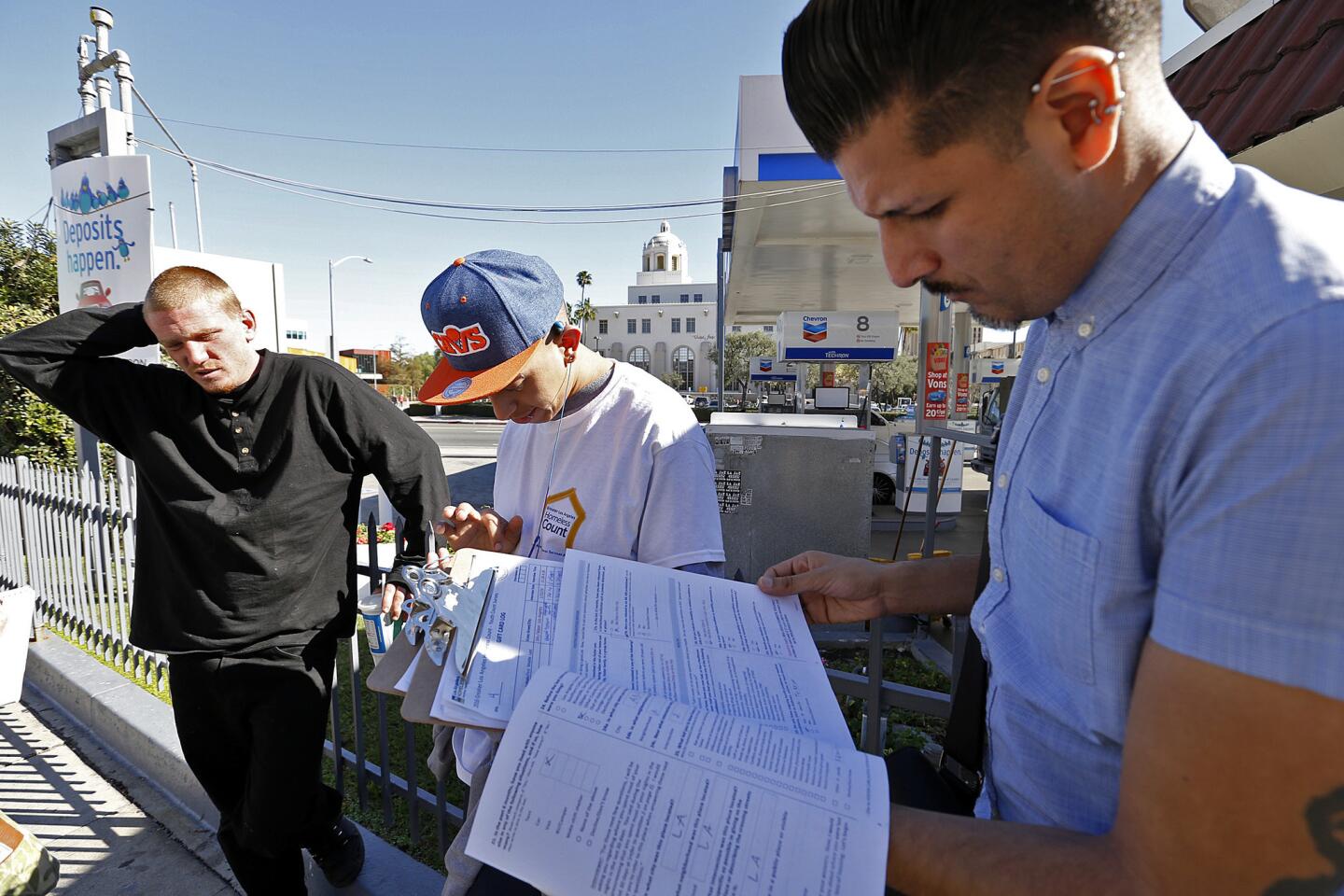

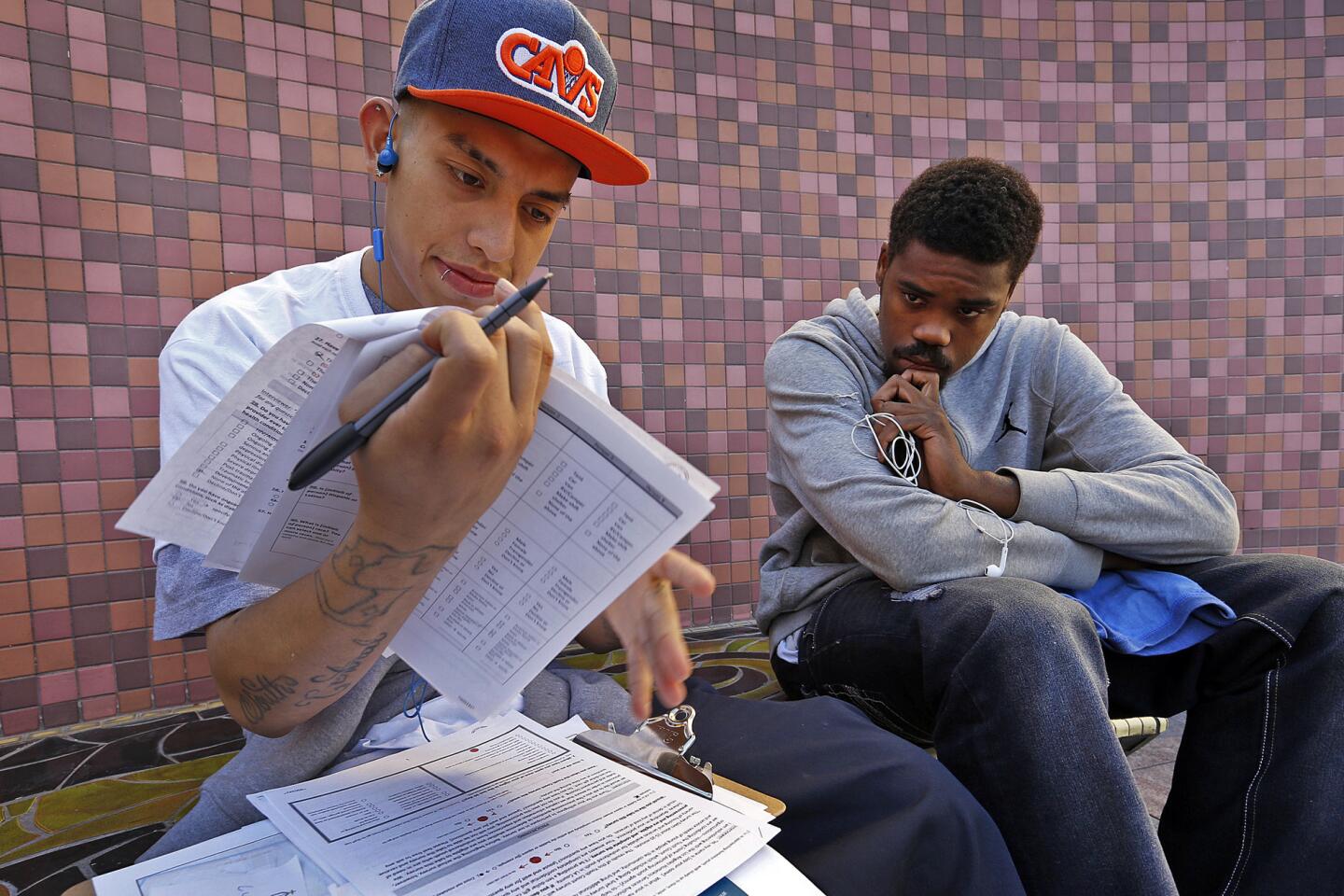

Sibrian and others from Jovenes Inc., the youth housing and service agency where Sibrian lives, were taking part in L.A.’s official homeless tally, which started Tuesday. Their task was to seek out those 24 and younger — unsheltered homeless youth counting unsheltered homeless youth.

The specialized count emerged from a growing consensus that young adults form a hidden homeless population, cycling on and off the street, and from city to city. They avoid shelters and other adult services, and often reject the label “homeless” because of the stigma, officials said.

Volunteers survey homeless youth under 25

They are also more likely than their elders to couch-surf or crash with friends. The U.S. Department of Education considers such arrangements homelessness, but Housing and Urban Development — which controls most federal aid to homeless people — does not.

Still, HUD recently relaxed its homeless criteria, giving local agencies limited authority to increase funding to young people under broader federal definitions. The agency is also funding a pilot project for foster youth, up to half of whom struggle with homelessness after they leave the system.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority tried a “street count” of homeless young people last year, but HUD was dissatisfied with the methodology and the results were not included in the official tabulation reported to Congress.

HUD was consulted in developing this year’s count. The survey is made up of 45 increasingly intimate questions, probing for histories of mental illness, drug use, domestic violence, sexual orientation and family discord. The survey results and shelter counts, combined with separate demographic surveys, are used to help officials calculate what they say will be a more realistic picture of homelessness among young people.

But a bigger hope is that officials will learn how, why and where young adults become homeless.

On Tuesday morning, after lengthy training, a small team of volunteers and Jovenes clients set out on foot, across the Spanish baroque Cesar Chavez Bridge over the Los Angeles River, to Union Station and Olvera Street — preselected homeless youth “hot spots.”

Sibrian found Dijuan Stuart sitting on the stairs leading up to the imposing Metro headquarters. Stuart, 21, said he’d been homeless on and off since age 16.

“My family didn’t want anything to do with me” after foster care, Stuart told Sibrian.

Several young men said they were in the streets because of family discord. Another said he recently left Men’s Central Jail.

Some of the Jovenes clients and the homeless people they interviewed had come from other states, looking for greater opportunities.

“If you go to the South, there isn’t too much going on,” said Jovenes client Mitchell Bowen, 24, who is from Georgia.

Lisa Biagiotti joins homeless youth social workers with Covenant House as they canvass Hollywood for 18- to 24-year-olds. An estimated 2,000 young adults sleep on the streets of Los Angeles every night. Down alleyways and side streets, Lisa meets Kr

Another Jovenes client, Javier Martinez of Bakersfield, said the surveys only began to scratch the surface of the trauma and hardship many of the young people had been through.

“For every one of them, there are 120 different stories,” said Martinez, 21. “My life is a fairy tale compared to theirs.”

The young men were eager for the $10 sandwich shop gift cards they got in exchange for filling out the questionnaires. Several said they were also grateful someone bothered to count them.

“You guys are out here doing a service,” said Kenneth Ferguson Jr. “Not everybody can see what’s going on.”

Twitter: @geholland

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.