Medi-Cal programs to the state: Can we stop printing and mailing directories the size of phone books?

- Share via

In Los Angeles County, signing up for Medi-Cal is often followed by a phone book-sized directory landing on your doorstep.

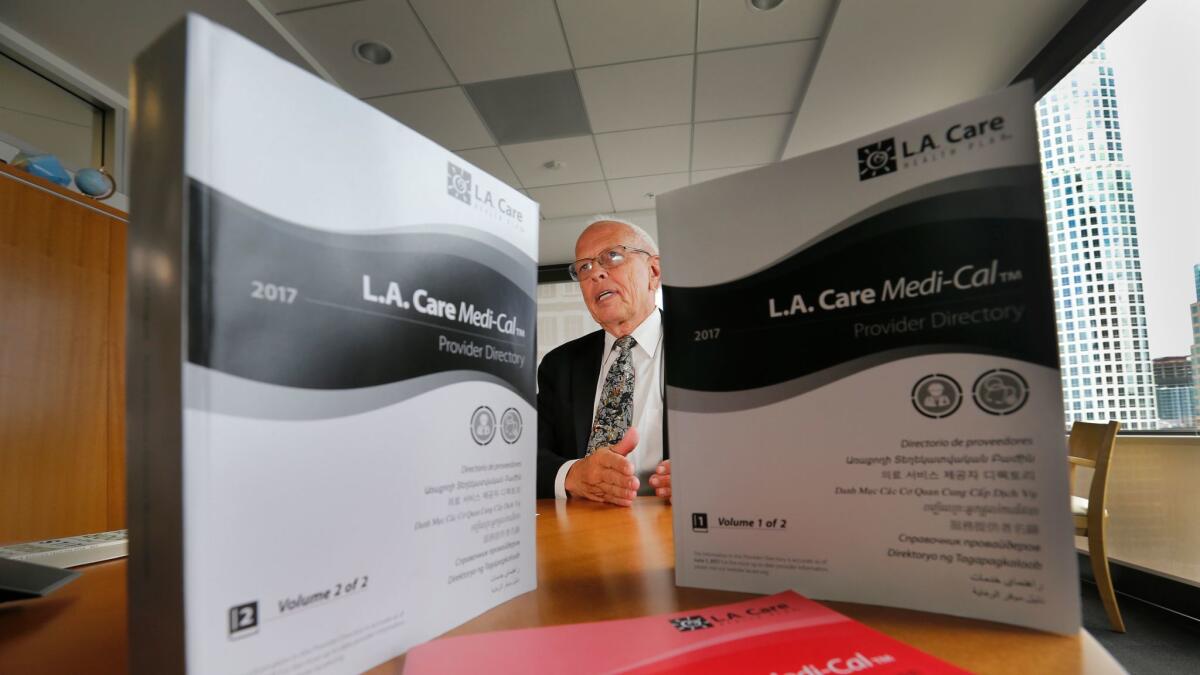

The 2017 directory for L.A. Care, a local Medi-Cal health plan, is 2,546 pages of doctors’ names listed by city, by specialty — anesthesiologists, gastroenterologists, ophthalmologists. It includes hours, addresses, phone numbers and languages spoken for each of the thousands of physicians.

The directory weighs more than 7 pounds. It wouldn’t fit in most mailboxes. And it can quickly become obsolete.

“It’s out of date the minute it comes off the press,” said John Baackes, chief executive of L.A. Care Health Plan.

Doctors frequently change their information or drop in and out of the network, so the health plan updates an online version daily. But for years, health plans across the state have been required to mail these printed directories to people who sign up for Medi-Cal.

Five million people have joined Medi-Cal since it was expanded under the Affordable Care Act in 2014, which means at least as many directories have been mailed out — at a cost of tens of millions of dollars.

Now L.A. Care and other Medi-Cal managed care plans are asking the state for permission to stop automatically mailing a directory to every enrollee. State officials say they’re reviewing the proposals.

The push for online directories is an example of how Medicaid programs that ballooned under the law known as Obamacare are refining operations and looking for ways to save money while insuring so many people. It also reveals the sometimes slow pace of change in such a big program — and the way costs add up quickly when every policy affects millions.

In 2014, the Affordable Care Act gave states money to expand their Medicaid programs, which insure low-income Americans and are jointly paid for by the state and federal government.

From the end of 2013 to the spring of this year, total enrollment in Medi-Cal jumped from 8.6 million to 13.5 million, or more than a third of all California residents, according to state data.

With that growth also came an increase in the number of doctors willing to take Medi-Cal patients and the size of the directories through which patients can learn who those doctors are.

L.A. Care’s directory was so big this year that it had to be split into two books, each the size of a phone book. Other counties’ have grown as well, but Los Angeles has the most Medi-Cal members — 4 million — and participating doctors.

“It’s more ridiculous with us because of our size,” Baackes said.

Printing and mailing cost $9 to $13 for each set of books, according to L.A. Care spokesman Hector Andrade. That puts the tab for the directories sent to the 90,000 people who joined L.A. Care over the last 12 months at roughly $1 million.

Until this year, L.A. Care was also sending them annually to all Medi-Cal enrollees in the health plan, which totals 2 million. Baackes said they mailed directories for the 5,000 homeless members to the L.A. County social services office, where they’re likely thrown out.

Baackes submitted a proposal in June to the California Department of Health Care Services, which runs Medi-Cal, requesting that the plan be allowed to instead mail a postcard to enrollees with a link to the online directories and an option to be mailed a printed copy.

Medi-Cal health plans across the state, including Health Net and Molina Healthcare, said they were also trying to work with the state to be allowed to provide virtual directories.

State officials said they were reviewing the proposals. A recent change in federal rules should allow them to go through, they said. Medicare, which insures Americans 65 and older, has allowed its managed care plans to email a directory or provide a link on their websites since 2011, said Jack Cheevers, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Critics of Medicaid, which covers 75 million Americans, say that the program is bloated and unsustainable. Proposals by GOP leaders to repeal Obamacare earlier this year included capping funding for Medicaid, saying the approach would force states to trim costs and find inefficiencies.

But Baackes said he didn’t think state officials were dragging their feet and that the problem was merely “symptomatic of trying to keep technology up with the rules and regulations.”

Chris Perrone with the California Health Care Foundation said state health administrators are regularly looking for ways to reduce expenses. He said they’re probably trying to ensure that patients having to request directories instead of automatically getting them in the mail doesn’t slow down how long it takes to make an appointment with a doctor.

“I don’t think it’s for lack of incentive that sometimes these things don’t happen,” Perrone said. “States already have skin in the game.”

Medi-Cal is expected to cost about $107 billion this fiscal year, and the state is on the hook for $38 billion of that, according to state budget.

Perrone said he’s collaborating with Medi-Cal and Covered California, the state’s insurance marketplace, that’s working to reduce big areas of spending: cesarean sections, opioid abuse and low-back pain. Medi-Cal officials have also said they’re working to identify patients who rack up large bills by overusing emergency rooms or because they’re addicted to drugs, so they can direct them to recovery programs or connect them with behavioral health treatment.

L.A. Care has invested in offering free exercise classes and nutrition advice to keep people healthy and prevent costs down the road. It is also trying to cut layers of bureaucracy by contracting with doctors directly, Baackes said.

He said he thinks the people who work with Medi-Cal patients and doctors daily should tell regulators where money is being wasted and propose ways to increase efficiency.

“I think that’s our obligation to do this,” he said.

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Twitter: @skarlamangla

ALSO

She watched her ex-husband end his life under California’s new right-to-die law. ‘I felt proud’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.