Reminders of a bohemian artist’s past will soon fade at Laird’s Landing

- Share via

Reporting from Point Reyes National Seashore — Paul Engel tapped the brakes of the Explorer as the dirt road curved and dropped into Laird’s Landing. Coyote brush hemmed the narrow, rutted track. He then stopped. A fallen pine limb blocked the way.

He first visited Laird’s four years earlier as the new archaeologist of Point Reyes National Seashore, and the cottages, ahead beneath the trees, gave him the creeps.

Abandoned on the edge of Tomales Bay since the 1990s, they seemed ready for a flood tide to whisk them away. Ivy snaked over their roofs. Branches fallen on the decks trellised mounds of poison oak.

Shadowy and sagging from rot, windows broken, walls tagged, beer cans crushed in darkened corners, they had helped protect whatever lay beneath the earth, the ancient repositories of so many forgotten stories. But now, on this late winter morning last year, time was running out.

The park service proposed to tear them down. Evaluations had been made, funding secured.

Engel, though, believed they deserved to be saved, rare evidence of the Coast Miwok’s tenure on this coast going back centuries.

And there was something else.

The National Park Service to decide how to preserve and interpret his home for future visitors.

Beyond the simplicity of these four-square walls, a more strange flourishing had taken place. Walls had been pushed out, rooms added with a gerrymandered ease, windows framed in angles like the facets of a diamond.

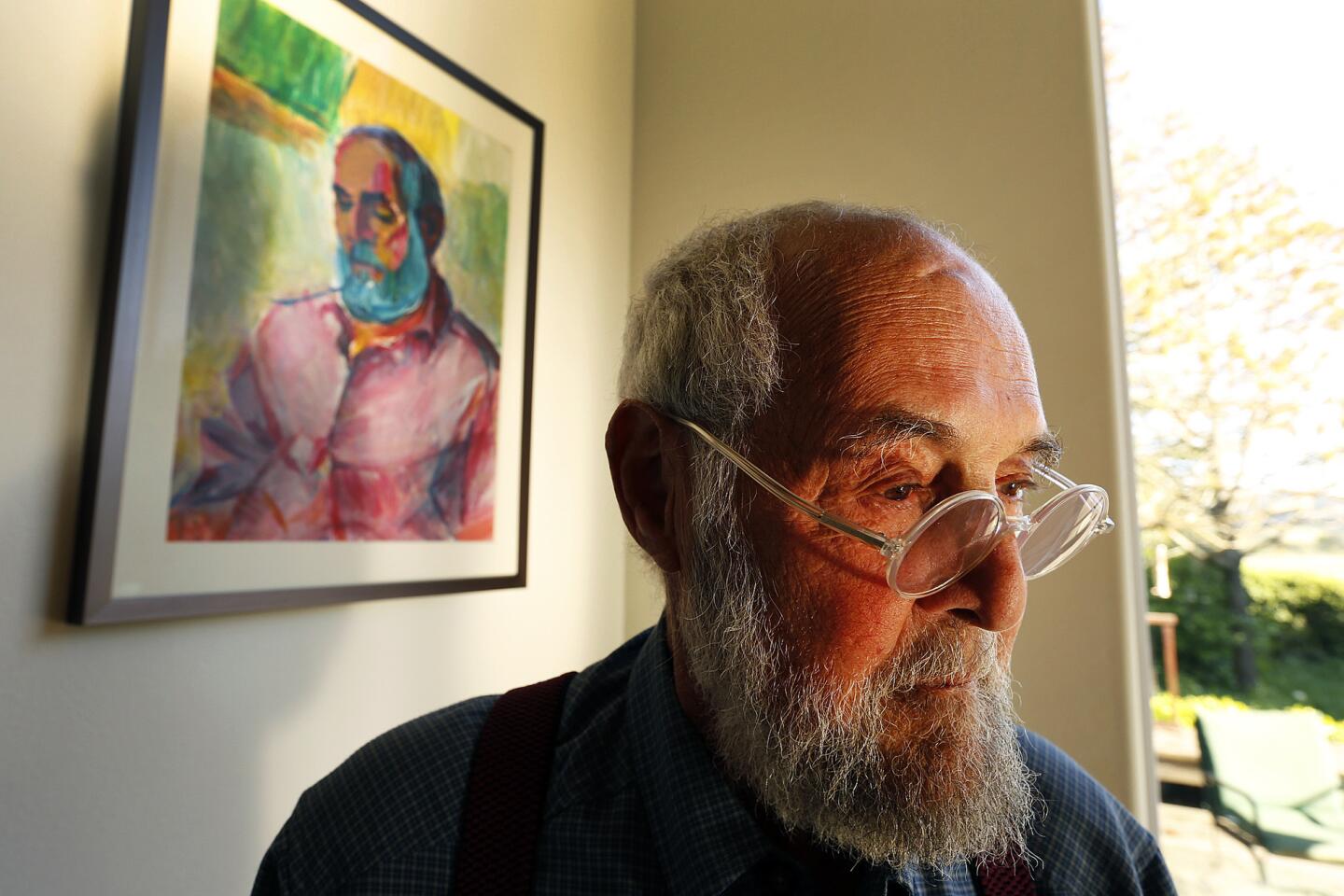

Laird’s Landing bore the stamp not just of the Coast Miwok but of Clayton Lewis, fisherman, artist, resident bohemian who had eked out a living here for 31 years. He died in 1995 in a room just off his studio.

His was the more eccentric contribution to these shacks, an architectural aesthetic belonging to the 1960s and ‘70s, too recent to be appreciated, too improvisational to be held onto. No wonder the park service — obliged by law to assess historic properties — didn’t know what to do with them, easier to let time take its sad toll.

::

Fifty miles northwest of San Francisco, Point Reyes juts into the Pacific, a wedge of chaparral that the continent seems eager to slough off. Local tribes call it a hummingbird’s beak.

Here the Pacific Plate grinds against North America, with the San Andreas Fault lying beneath a narrow inlet, 12 miles long and one mile wide, known as Tomales Bay.

Laurel and oak forests draped in wolf lichen line seasonal creeks that roll down from treeless ridgelines. Tides open and close upon isolated beaches and coves. On windy days, white caps scallop the bay. On windless days, the water is cloaked in fog or bathed in sequined light.

In the spring of 1964, Lewis discovered Laird’s. Tiller in hand, he sailed out of Marshall on a friend’s boat. He was 49, visiting with his girlfriend, and about to discover his future in some shacks sheltered by cypresses on the beach.

The previous decade had had ups and downs: a three-year stint in Los Angeles at the Herman Miller furniture company; time in Marin County, buying a farmhouse, getting foreclosed. Then there was the affair, the end of his marriage, losing his two younger children to the custody of his soon-to-be ex.

He was ready to cut free of it, leave behind the cookie-cutter suburbs transforming America and devote himself to his art.

Point Reyes National Seashore was 2 years old, just establishing its boundaries. Laird’s was privately owned. Lewis contacted the owner. They struck a deal: rent for free and $5 an hour for repairs. Lewis, Judy Perlman and her 1-year-old son settled in.

Lewis stabilized foundations, fixed the roof and rolled out linoleum. He added flourishes — corbels, flower boxes, and for the guest cottage, an elaborate bed and eventually a two-story tower — all from wood scavenged at local dumps.

Propane heated the spring water and kept the stove and refrigerator running. Oil lamps brought a glow to the night.

The park service acquired the property in 1972 and tried to get him to leave, but the Point Reyes community rallied to his support. He was given a new lease, starting at $75 a month.

::

Engel walked a path to the water. He had been asked to evaluate the site before the demolition, to learn more about Lewis’ work here.

From the high tide mark, the 31-year-old Sonoma State graduate paced transects west to east, east to west, each a few meters in from the next. Tiny pink flags marked foundation piers, shell fragments, pieces of glass. They told an important story; he just had to fit them together.

So far as the written record showed, Domingo Felix and Euphrasia Valencia were the first residents of Laird’s. He was Filipino, and she, Coast Miwok. They moved here in 1861, a significant step for a family long displaced from ancestral lands by the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans.

A tenant farmer at Laird’s, he fished and probably worked for the dairy ranchers who subdivided the peninsula after statehood. Their children went to school at the neighboring ranch. A son is thought to have built the cottages from the wood of a shipwreck.

Through the Depression and two world wars, Laird’s was home for this family for five generations until they were evicted in 1955. They tried to make a case in court, but without a title or property tax receipts, they had no claim.

After their departure, the county zoned the property for 7,500-square-foot lots and single-family homes, but the creation of the national park froze the Coast Miwok homes in time.

Peter Lewis, youngest son of artist Clayton Lewis, inspects the roof of the guest house at Laird’s Landing in Point Reyes National Seashore.

Engel stepped into the main house. The floor felt soft in places, but the siding seemed sound. He touched one of the planks and saw a slight scar marring the redwood grain. It was from a circular saw, not a band saw, suggesting it had been ripped in some lumber yard on the North Coast more than a century ago.

Native histories, Engel knew, are often reassembled from discarded objects, arrowheads and flakes of chipped stone that tell a familiar yet incomplete story. Harder to find, however, are examples of life in modern times, which is what makes these cottages unique.

As he packed up his gear, the afternoon light brightened the hills across the bay. At his feet, seashells speckled the soil.

Scratch the surface, and Lewis would be found here too.

::

Lewis was a legend in the Point Reyes community, as inescapable as his red Volvo or his bright Guatemalan shirts and bowler hat.

Charming and charismatic, he befriended a raven he called Nevermore, and in front of friends and strangers who dropped in on him, he held court, his words gospel for anyone who thought he was living the hippie dream.

He complained about the interruptions, but he liked the company. Life out here was lonely after Judy left. He hoped to find the right woman to share this life, but his romances often burned bright and burned out.

His youngest son, Peter, visited during the summer. A teenager in the 1970s, he and his father enjoyed fishing together, setting a beach seine in the cove and feeling the concussion of the fish striking the net, watching their silvery colors emerge in watery light. The bay seldom disappointed them.

Lewis made chowder, baked bread, grew lettuce in the garden. Living here was hard, and it often kept him from the jewelry, paintings and sculptures he dreamed of.

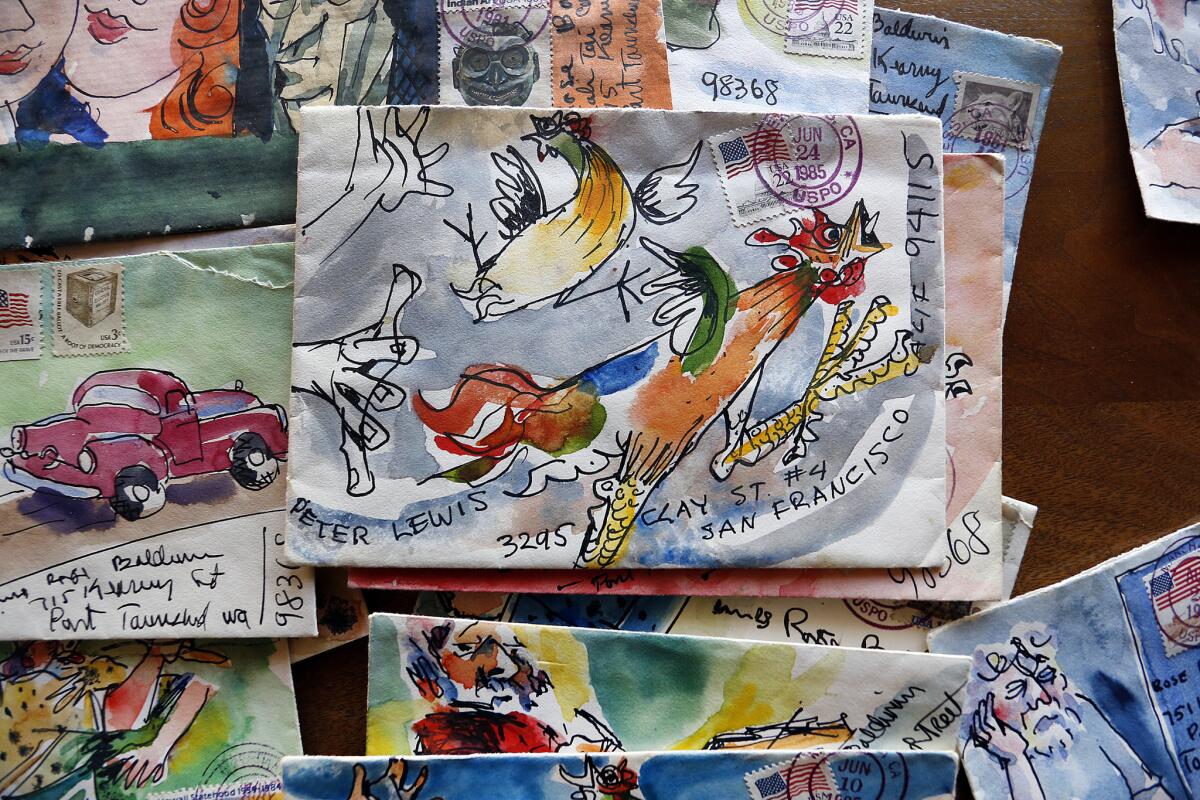

The easiest expressions were the cartoons that accompanied letters to his mother in Washington, an attempt to cheer her in her final years. Explosions of color and wit and energy, these watercolor and ink drawings decorated envelops with images ribald and comical, exaggerated and wistful.

A few of the hundreds of cartoons crafted by artist Clayton Lewis on envelopes that accompanied letters he mailed to friends, family and his mother living in Washington.

Lying on his back staring at a skein of geese in the sky, climbing a ladder to the stars or levitating on one finger, naked above the Earth, he showed an abiding commitment not to take himself seriously.

Yet he still tried to get a show, find a gallery, publish a book, but the art market had diminished.

Teetering between ambition and distraction, Lewis found himself struggling. In his later years, he talked about moving, finding a place to live out of the wind and cold, but he had little money. Disheartened by his prospects, he tried to remain cheerful, in his letters at least:

La de da! The world is beaming and God is kind. Everywhere there is blue sky and cool sunshine. No wind. No fuss. The birds are twittering and all is well!

By late summer 1995, the end of another season on the coast, the cancer had spread, and Lewis was in pain. Weed had helped, but the morphine pump worked best.

He lay on his bed and heard the wind soughing through the pines, the distant voices of friends and family. He called to Peter.

“I need you to protect my art,” he said.

::

Honoring his father’s legacy has preoccupied Peter since that September day.

After Lewis’ death, friends talked about starting a residency program at the cove for artists and writers, but the park service said no. The site was too remote, too unimproved, and when another location was offered, the friends declined.

Momentum stalled, discussions grew less frequent, and Peter turned to his own career as a composer. The superintendent said the buildings would be preserved, but that was 20 years ago.

In conversations with Engel, Peter found a sympathetic listener.

Engel knew the ‘60s in California were disappearing, the artifacts of that era lost to neglect or indifference. At Olompali State Park, archaeologists had combed through the burned-down ruins of the Burdell Mansion, home of a commune known as the Chosen Family, recovering incense holders and warped LPs from the Acid Test era.

In Muir Woods, the park service was reviewing the status of Druid Heights, where Alan Watts, Gary Snyder and other artists, poets and philosophers had cobbled together homes with no allegiance to building codes or convention.

Engel found a 1973 book — “Handmade Houses: A Guide to Woodbutcher’s Art” — a photographic anthology of ramshackle homes that featured Lewis’ guest cottage and the elaborate bed, its four posts like totem poles. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art exhibited it in 1999 in a show of counterculture art.

Trees frame a view of Tomales Bay as Peter Lewis, youngest son of artist Clayton Lewis, walks to the original Coast Miwok buildings at Laird’s Landing in Point Reyes National Seashore.

Through news stories, memories and photographs, Lewis’ ghost began to speak to Engel as clearly as Domingo and Euphrasia’s voices did. His architectural additions — the prism-like windows, the tower beside the guest cottage — belonged to the spirit of a man who, like his predecessors, found a way to live on the edge of this bay.

For Lewis and the Coast Miwok, these shacks represented a time and a place in California’s not-so-distant past when it was possible, even desirable, to get lost and be forgotten. But Engel worried they were too broken to be saved.

He forwarded his report to the park superintendent, who made a decision on March 24. The shacks at Laird’s Landing would be preserved to reflect the Coast Miwok presence on the coast.

Lewis’ additions, according to the park service, were not historic and would eventually all be torn down. They were too impractical, too costly to preserve.

::

Bohemia attracts its own destruction, said Richard Kirschman, an old friend of Lewis’. Lewis lived on the edge, and the edge was crumbling.

But if the history of California once lay in its attraction for visionaries and outliers, didn’t his home deserve to be preserved other than on a website or through interpretive signs?

After Lewis died, he was dressed in his favorite Guatemalan shirt, bright yellow pants and bowler. He was placed on a slab of cypress, flowers arranged around him.

Neighbors in town waved as the procession passed. More than 300 people attended the memorial, and his ashes were scattered in the bay.

A year later, Life magazine published a photograph of Lewis, showing Point Reyes’ resident artist standing on his deck at twilight, dressed in a knit sweater, holding a pipe.

The bay spread before him, its waters catching the purple light of the setting sun. A small boat rode at anchor; a tree swing hung from a cypress.

“Is California Over?” its editors asked.

Twitter: @tcurwen

ALSO

Are you an independent voter? You aren’t if you checked this box.

Wife of jailed Vietnamese human rights activist comes to U.S. with a plea

Manson follower Leslie Van Houten faces fight from victim’s family to gain freedom

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.