How an ex-FBI profiler helped put an innocent man behind bars

- Share via

Exasperated, Jeffrey Ehrlich paused the true-crime television show every couple of minutes. The same thought kept running through the attorney’s mind: “No, that's wrong.”

The episode of “Killer Instinct” highlighted how the work of a retired FBI profiler had helped convict Ehrlich’s client of killing an 18-year-old woman in a Palmdale parking lot.

There were no fingerprints left behind, no murder weapon. But clues from the crime scene caught the profiler’s attention. The driver’s-side window of the victim’s car had been lowered several inches, suggesting to the profiler that the teen had rolled it down when someone who looked trustworthy approached. And her tube top was askew — a sign, the profiler said, of a botched sexual assault.

“No, no, no,” Ehrlich said, stopping the show again. He thought the episode — titled “Sudden Death” — needed a new name: “Here’s How We Convicted an Innocent Man of Murder.”

Years after the profiler’s testimony helped secure a murder conviction, the case against Ehrlich’s client, Raymond Lee Jennings, has unraveled in dramatic fashion.

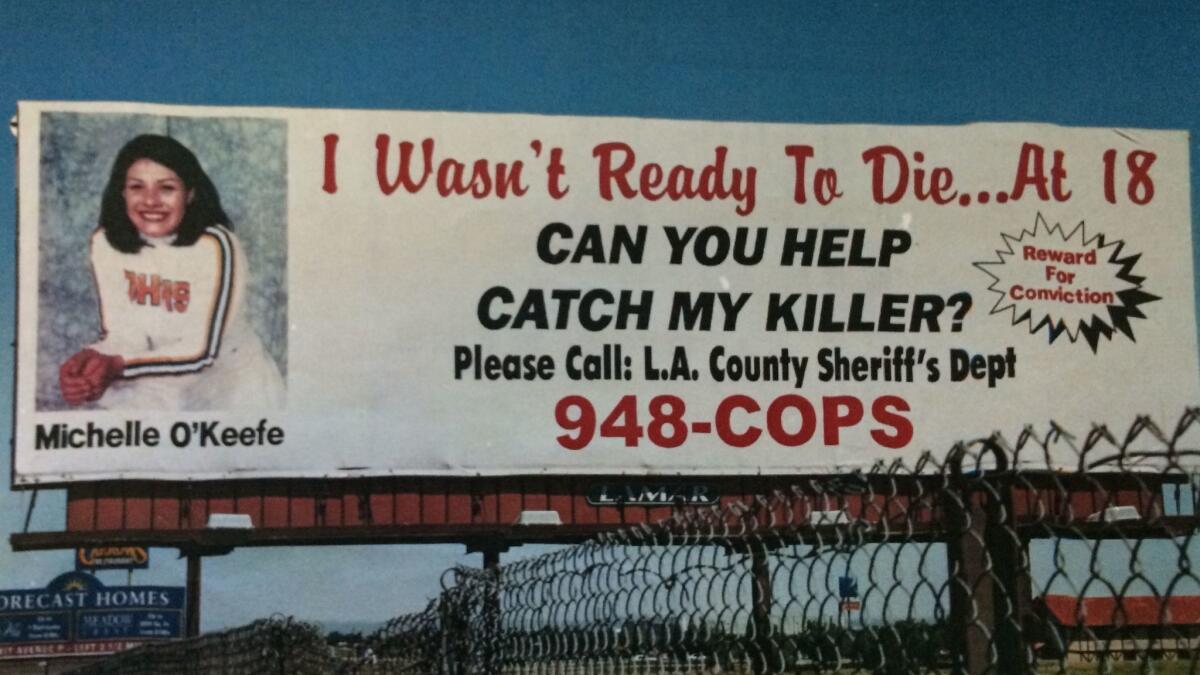

After reinvestigating the case, authorities now suspect gang members killed Michelle O’Keefe and that the motive was robbery, not sexual assault. The profiler, Mark Safarik, has withdrawn his testimony. And a judge earlier this year declared Jennings — the security guard who patrolled the lot the night of the murder — factually innocent, putting a capstone on his legal nightmare that included 11 years behind bars.

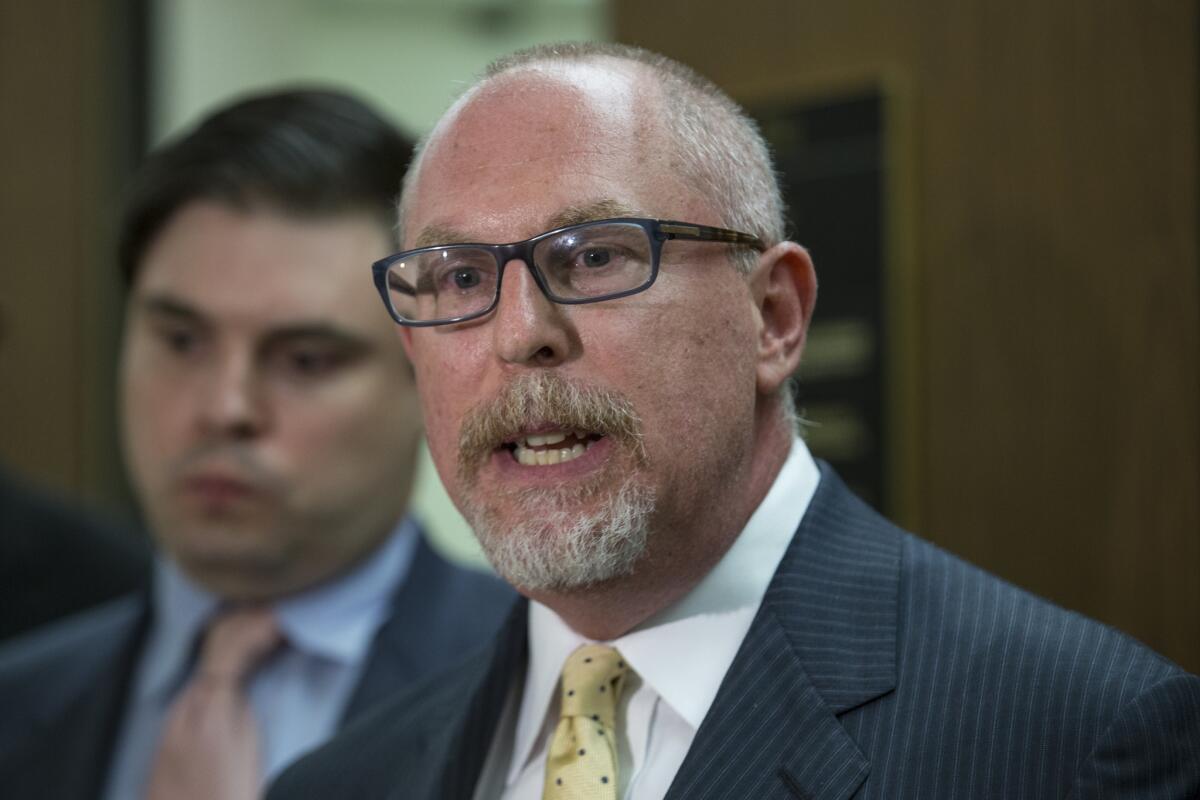

The wrongful conviction has renewed questions about the credibility of profiling and focused attention on the role played by Safarik, the star of the season-long television show “Killer Instinct,” whose testimony was considered crucial at Jennings’ trial.

In an interview with The Times, Safarik defended his analysis of the crime scene, saying he still harbors doubts about Jennings’ innocence. He agreed to withdraw his testimony, he said, after learning that homicide investigators hadn’t interviewed everyone who had been at the scene of the killing, but having the information wouldn’t have necessarily led him to a different conclusion.

In recent decades, profilers have captured the public’s imagination as the stars of a plethora of television shows and movies. In the real world, they work to help detectives predict the likely characteristics of a criminal in an unsolved case and explain to jurors how evidence left at crime scenes can reveal a killer’s motive or modus operandi.

But there is a deep chasm in legal and academic circles about how much credibility to give profilers. Many detectives credit them with helping investigations, but some researchers have criticized profiling as nothing more than glorified guesswork.

The murder

It was 2006 and Safarik would soon retire from the FBI, but not before looking into the 6-year-old murder case of O’Keefe. The college student died after bullets tore through her head and neck as she sat in her blue Mustang in a desolate park-and-ride lot patrolled by a security guard.

Safarik spent more than a decade in Quantico, Va., studying crime scene evidence and writing offender profiles in serial killings, sexual assaults and stalking cases. In the O’Keefe investigation, Los Angeles prosecutors wanted two things from him: An assessment of crime scene evidence from the Feb. 22, 2000, shooting and an opinion on the killer’s motive.

Jennings was arrested in 2005, but the case against him was thin, based only on circumstantial evidence. No blood or gunpowder was found on his security guard uniform, and male DNA under the victim’s fingernails didn’t match his.

In a report written shortly after his retirement in 2007, Safarik stopped short of identifying Jennings as the killer but noted some of the same inconsistent statements by the security guard that had initially raised the suspicion of detectives.

Jennings, for instance, initially denied seeing any cars leave the lot after the shooting. Later, he admitted he’d spoken to a female driver who had stopped to ask him what happened as she drove away. The security guard also told investigators he saw O’Keefe’s body “twitching” when he arrived at her car several minutes after the shooting — something a forensic pathologist said was “beyond the limits of credibility.”

A prosecutor argued at trial that Jennings had lied to cover up his involvement in the crime. Two separate juries in downtown L.A. deadlocked before the case was moved to the Antelope Valley for a third and last trial.

Safarik, who testified in all three, was the prosecution’s final witness in the third. He told jurors he’d assessed or reviewed at least 4,000 crime scenes — many of them complex homicide cases — and had written numerous articles and book chapters.

“When you start to look at that many cases,” he told jurors, “you start to see patterns in behavior.”

Safarik explained to jurors how he'd eliminated several possible motives for O’Keefe’s murder.

He stressed there was no history of gang crime in the lot and said it didn’t appear to be a targeted personal attack, noting that O’Keefe didn't have a boyfriend or a criminal record. Robbery didn't make sense, he said, noting that O’Keefe’s wallet containing more than $100 was left in her car, and that her blue Mustang wasn’t taken. And, the parking lot was lighted and patrolled by a guard.

The blood spatter at the scene, he told jurors, showed that the killer had first confronted O’Keefe as she stood outside her car. Her tube top was pulled down, he noted, partially exposing her breasts.

“I believe that the motive for this crime was sexual assault,” Safarik said. “It went bad quickly and it escalated into a homicide.”

The prosecutor argued that Safarik’s testimony explained a clear motive for Jennings to kill O’Keefe: He panicked after attempting to sexually assault her.

During deliberations, jurors asked to be read back Safarik’s testimony. After more than three weeks, the jury convicted Jennings of second-degree murder.

At his sentencing hearing in 2010, Jennings — who always maintained his innocence — was given 40 years to life in prison.

“This is one sin,” he told the court, “that I will not be judged for.”

Inside the mind of a killer

The idea of trying to get inside a killer’s mind stretches back centuries, but the modern popularity of profiling began in the 1970s with the creation of an FBI team now known as the Behavioral Analysis Unit.

The unit’s agents — officially called behavioral analysts — are trained to predict the personality traits and actions of an offender during an investigation by drawing on research of past cases and interviews with violent criminals.

There is very little scientific research testing the reliability of profiling, and the few existing studies have led to sharp disagreements over whether profilers can better predict the characteristics of criminals than nonprofilers.

Still, the public holds an outsized view of what profilers can do, said David Wilson, a professor of criminology at Birmingham City University in England who has written critically about profiling. Due in large part to shows such as “CSI” and “Criminal Minds,” as well as the film “Silence of the Lambs,” the public often views profilers as omniscient Sherlock Holmes-esque experts who can quickly identify a killer and decipher the motive, he said.

“We want to believe in that Holmesian figure that can turn up and magically solve the crime,” Wilson said.

California’s courts generally don’t allow testimony comparing a defendant to the characteristics of a “typical” criminal out of fear that such a profile could easily include innocent people. Judges do, however, often allow profilers to testify about crime scene evidence and what it reveals about possible motives, modus operandi or links to similar crimes by a common perpetrator.

We want to believe in that [Sherlock] Holmesian figure that can turn up and magically solve the crime.

— David Wilson, a criminology professor at Birmingham City University, on the public's fascination with profilers

Edward J. Imwinkelried, a professor emeritus at UC Davis who co-wrote the annotated California Evidence Code, said he finds nothing inherently wrong with Safarik’s method of drawing conclusions about motive from clues at the crime scene. But he said jurors shouldn’t give it the same weight as expert testimony that relies on theories supported by scientific tests, such as blood spatter.

“There’s an element of uncertainty,” Imwinkelried said.

Profilers can help detectives narrow a list of suspects during an investigation, but relying on their conclusions at a criminal trial carries a significant risk if they’re wrong, said Simon Cole, who teaches criminology, law and society at UC Irvine and directs the National Registry of Exonerations.

Cole reviewed Safarik’s testimony at Jennings’ trial for The Times and said the prosecution had used expert testimony to vouch for investigators’ theory about the crime.

“I was a little appalled,” he said. “It was police work in the guise of an expert witness.”

‘Killer Instinct’

A panel of state appeals justices upheld Jennings’ conviction in 2011, ruling that the trial judge wasn't wrong to allow Safarik to take the stand — in fact, they wrote, his testimony may have been crucial.

“Without it,” they wrote, “there was no evidence from which the jury might infer the motive.”

About a month before the ruling, the “Killer Instinct” episode about O’Keefe’s death debuted on the crime-drama channel Cloo.

“I analyze crime scenes from a unique perspective — inside the mind of the killer,” Safarik tells the audience at the start of each of the 13 episodes, which all focus on a case Safarik worked.

The episode about O’Keefe includes actual footage of a sheriff’s detective confronting Jennings in hopes of getting a confession. Jennings wipes his hand over his brow — a small gesture that Safarik assigns great weight.

“This is what poker players and profilers call ‘a tell,’ ” Safarik says. “So far he’s been bluffing, but Jennings’ body language here says, ‘I’m guilty.’ ”

Toward the end of the episode, jarring piano music pulses in the background as Safarik offers a monologue about Jennings.

“Like other killers I’ve known, he’s also arrogant and narcissistic — fatal traits that led to his demise,” Safarik says. “This was all his doing…. Ultimately, he was responsible for it.”

‘Wild, illogical speculation’

Ehrlich watched the show in frustration. Safarik, he said, was relying on “wild, illogical speculation.”

The lawyer hired another profiler, Peter Klismet Jr., to review Safarik’s assessment. In a report later cited by the judge who declared Jennings factually innocent, Klismet sharply criticized Safarik’s conclusions, saying many of his findings were not supported by “accepted principles of criminal profiling.” The crime, Klismet said, had all the signs of a robbery committed by a young offender, who kills the victim and then flees.

The car’s glove compartment was found open and O’Keefe’s cellphone was missing, he said. The killer, Klismet concluded, hadn’t seen her wallet because it was wedged between the seat and the center console.

As for her slightly lowered tube top, Klismet suggests many possible explanations. Perhaps she was in the process of changing into new clothes, as she was headed to a night college class, he said, or maybe her top slid down as she lifted her hands in defense after seeing a gun.

The lack of scratch marks on her chest, he said, suggested an attacker didn’t pull down her top. He argued that Safarik ignored evidence that contradicted his theory and based his assumption almost entirely on the position of O’Keefe’s tube top. The authorities homed in on Jennings as a suspect, Klismet said, and then worked backward and “made the facts fit.”

Ehrlich reached out to Safarik directly, saying there were serious concerns with the case and urging him to reconsider his assessment.

“Ray Jennings is going to be exonerated,” he wrote in an email. “It’s going to be a hell of a story. When that story is told, what will your role be?”

New evidence

At Ehrlich’s urging, the district attorney’s conviction review unit began reexamining the case. By June 2016, prosecutors were convinced someone other than Jennings killed O’Keefe and asked a judge to release him from prison.

In a letter to the court, Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. John Spillane explained that the woman who spoke to Jennings in the parking lot soon after the shooting was a 17-year-old gang member who is serving a five-year prison sentence for stabbing her boyfriend.

And an 18-year-old gang member, who was in her car that night, was suspected of taking part in a series of robberies and carjackings. He was arrested four months after O’Keefe’s death for a home invasion robbery that included the theft of a white Mustang, the letter said. A 9 mm handgun was used in the crime — the same type used to kill O’Keefe, Spillane wrote.

Read about the new evidence in the murder of Michelle O'Keefe »

At the time of the arrest, the letter said, the man was wearing a single, yellow metal earring with a white stone. O’Keefe was wearing similar earrings at the time of her death, and authorities believe that one might have been missing. The original homicide detectives never interviewed the man, who was sentenced in the home invasion robbery to 31 years in prison, the letter said.

Jennings, the letter said, had no criminal record, had served with the National Guard in Iraq and was helping a friend distribute Christian music around the time of the murder.

After learning of Jennings’ release, Safarik emailed Ehrlich, saying “if he is in fact innocent then that is a good thing.”

Two months later, Safarik withdrew his analysis, telling the court that he had relied on information from an incomplete investigation by L.A. County sheriff’s detectives. Had he known about its shortcomings, he wrote, “I would not have been able to formulate a reliable opinion.”

A totality of things

Nevertheless, in an interview with The Times, he said he still doubts Jennings’ innocence and believes the evidence supports his original theory of a sexual assault motive.

“I think it makes sense as I look at everything together,” said Safarik, who now works in private practice as a consultant.

Safarik vociferously denied having worked backward toward a conclusion or assigning too much weight to the positioning of O’Keefe’s tube top. It was the totality of things, he said, that shaped his finding.

For one, Safarik noted, even though it was cold outside at the time of her killing, the window of O’Keefe’s Mustang had been lowered about four inches. Jennings, dressed in uniform, would’ve looked trustworthy, he said. A gang member with a handgun would not.

Safarik said he considered the step of thoroughly investigating everyone at the crime scene so obvious — “Investigation 101,” he called it — that he assumed it had happened. Sheriff’s Det. Richard Longshore, the lead investigator on the case, died in 2013.

Safarik also stressed that he re-created the crime scene and found that Jennings, who said that he hadn’t seen the shooting, should’ve been able to see the killer from where he said he had been standing in the parking lot.

“Jennings has a lot of problems that were never explained and are still very, very problematic,” he said.

After his release last year, Jennings spent time reconnecting with his five children and began to look for work. On June 23 — the anniversary of his release from custody — he exchanged wedding vows with Kim, “my twin flame,” as he calls her. They bought a home together in North Carolina, Jennings said, and both plan to work in real estate.

Asked about Safarik, Jennings said he still remembers the wave of nausea that washed over him as he listened to the profiler testify at trial about attempted sexual assault. Jennings wondered, at times, if he might vomit and he kept his eyes on the jurors.

He wanted desperately to tell them that it wasn’t true, he said, and that it wasn’t in his nature to make an unwanted advance on a woman. As Safarik spoke, Jennings said he felt angry and hurt. He now views profilers with suspicion.

“How things may have happened,” he said, “doesn’t mean it’s how they did happen.”

For more news on the Los Angeles County courts, follow me on Twitter: @marisagerber

ALSO

Nevada parole board to consider O.J. Simpson's bid for freedom

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.