Unity urged at memorial for man killed by police on skid row

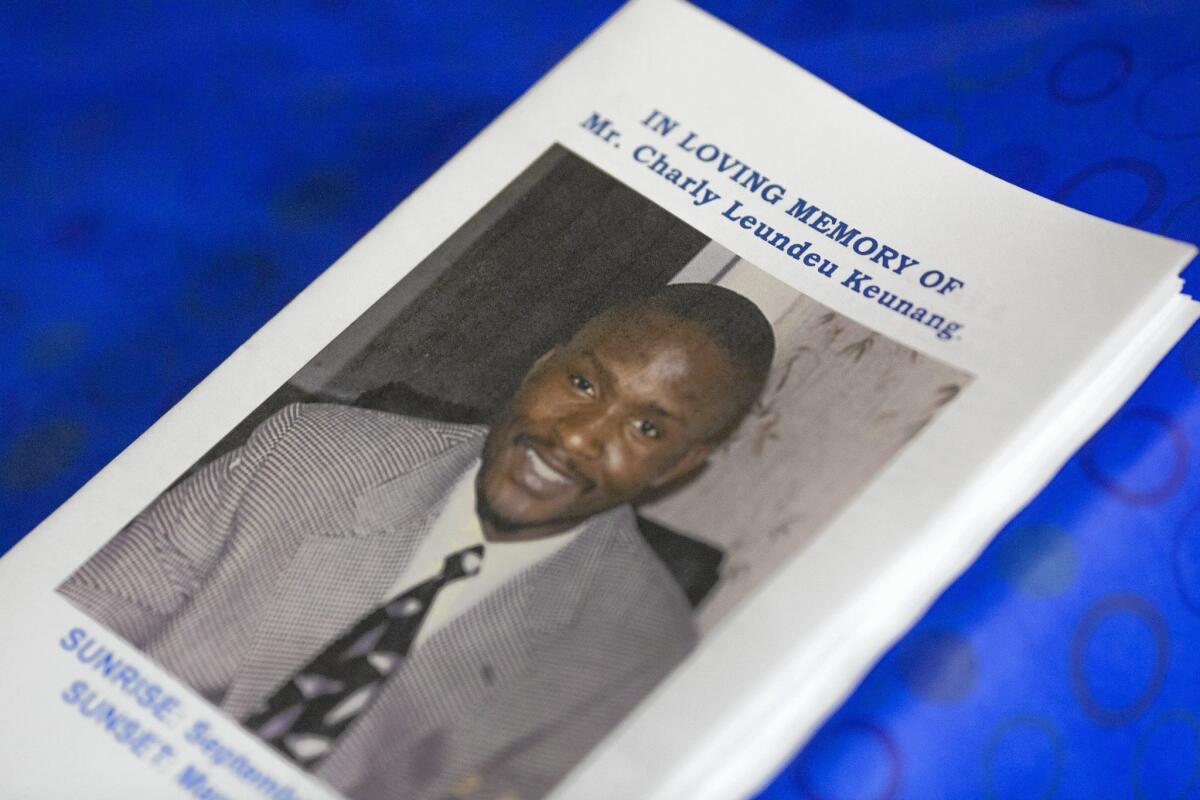

Calling for Pan-African unity in the protest movement against police violence, eight church leaders led a fiery service Saturday for Charly Leundeu Keunang, a homeless man shot and killed on skid row by Los Angeles police in a videotaped struggle seen around the world.

The Rev. Kelvin Sauls of Holman United Methodist Church, who lent his West Adams sanctuary for the memorial, tied Keunang’s March 1 death to controversial police killings of African American men nationwide.

“Whether it’s Ezell Ford, or whether it’s Michael Brown or Trayvon Martin, we have seen an ongoing challenge around police brutality as regards black men,” said Sauls, a South African immigrant.

Keunang, 43, died during a tussle with six Los Angeles police officers responding to a robbery report. Keunang’s mother, Heleine Tchayou, and other family members have filed a $20-million claim against police and the city.

Police Chief Charlie Beck said Keunang struggled with an officer over his gun. Witness accounts were conflicting, but several disputed Beck’s account.

Keunang came from Cameroon in West Africa, and was known on skid row as “Africa.” He arrived in Los Angeles under an assumed identity in 1997 to study acting and spent 14 years in federal prison on a bank robbery conviction.

During the memorial service, several clergymen assailed police and the media for what they said was an attempt to use Keunang’s homeless status and criminal record to vilify him and discount his death.

“They wanted to position this and say to society this man was someone we could throw away,” said the Rev. Gregory L. Johnson, of West Angeles Church of God in Christ.

“When is our mayor and the supervisors going to understand that every person is valuable?” said Pastor William Smart, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Southern California. The speeches were frequently interrupted by applause and chants of “They can’t kill Africa.”

Tchayou, who traveled from Boston with her daughter and granddaughter for the ceremony, collapsed sobbing in the church next to Keunang’s open casket, saying in French, her native language, “My son, my dear, why, why?”

Marianne Bema, who said she came to represent 300 members of Rancho Cucamonga’s Cameroonian community, said Tchayou was crying out for her son to explain why the police shot him when he didn’t kill anyone. Attorney Dan Stormer said no one from the Los Angeles Police Department had contacted the family.

Many of the mourners did not know Keunang but described themselves as members of the African diaspora there to support the family and their immigrant communities.

“Charly came to American like so many other people, chasing his dreams,” Smart said. “Something happens and their visions crumble, and most of the time it’s Americans’ fault.”

Tchayou and Line Foming, Keunang’s sister, were escorted into the church by Jose Maldonado, who put Keunang up at his suburban Los Angeles home after Keunang was released from prison in 2014. Maldonado said Keunang, who spent years in a prison mental hospital, was a humanitarian and highly intelligent, with no apparent psychiatric problems.

“People may not have understood him,” Maldonado said.

During the service, a musician played a kora, a harp-like West African instrument. Later that night, about 50 people, many in robes of African cloth, gathered at a hall near the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza for a wake.

As the evening wound down, guests danced in a circle to Nigerian gospel music. Tchayou, leaning on a cane, briefly joined the processional, then, pointing to a blown-up photo of Keunang framed in traditional Cameroonian Bamileke cloth, sat down again.

David Singui, a Los Angeles businessman who helped organize the wake, asked for donations to help the family send Keunang’s body back to Cameroon for burial.

“This lady has seen her son killed on national television,” Singui said. Only later was she told the man on the video was her son, he added.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.