San Francisco is likely to approve Laura’s Law mental health program

- Share via

Reporting From San Francisco — Family members of those who have suffered multiple mental health crises and refuse help or fail to stick with it are begging for a Laura’s Law program — which could court-order the intractably ill into outpatient treatment. Police officers and firefighters who see the same people cycle through hospitalizations and jail want it too.

Then there are the mental health consumers who are well enough to speak of the trauma inflicted by coercive care. It doesn’t work, they say. It drives people from treatment.

The debate has played out in board chambers of elected leaders since a law authorizing California counties to launch such programs took effect in 2003. And for 11 years, there have been almost no takers but for Nevada County, where the law’s namesake, 19-year-old Laura Wilcox, was gunned down by a behavioral health client who had stopped complying with his treatment.

But that is changing. Yolo County adopted a program in January after a test run. Orange County in May became the largest county to sign on. And San Francisco County’s Board of Supervisors on Tuesday will vote on whether to do so. Approval appears likely, given amendments that would allay some fears.

Under the program, court orders may be issued only for those who have been hospitalized or jailed because of mental illness twice in the last three years or who have been violent to themselves or others (or threatened such violence) in the last four. They must have been offered the chance to voluntarily follow a treatment plan and refused. Their condition must be “substantially deteriorating” and outpatient treatment deemed the least restrictive way to help.

The amendments, a first in the state, would require the county mental health director to set up a “care team” that includes a peer counselor and a family member of someone with mental illness. Voluntary treatment with the same level of outpatient services must be offered throughout the process and also made available to those who do not qualify for Laura’s Law. Law enforcement can step in to transport the person to a hospital only if there appears to be a current danger to self or others.

If the measure fails, Supervisor Mark Farrell and four colleagues have pledged to take the matter to voters in November, turning one of the most delicate policy issues of the day into a political campaign.

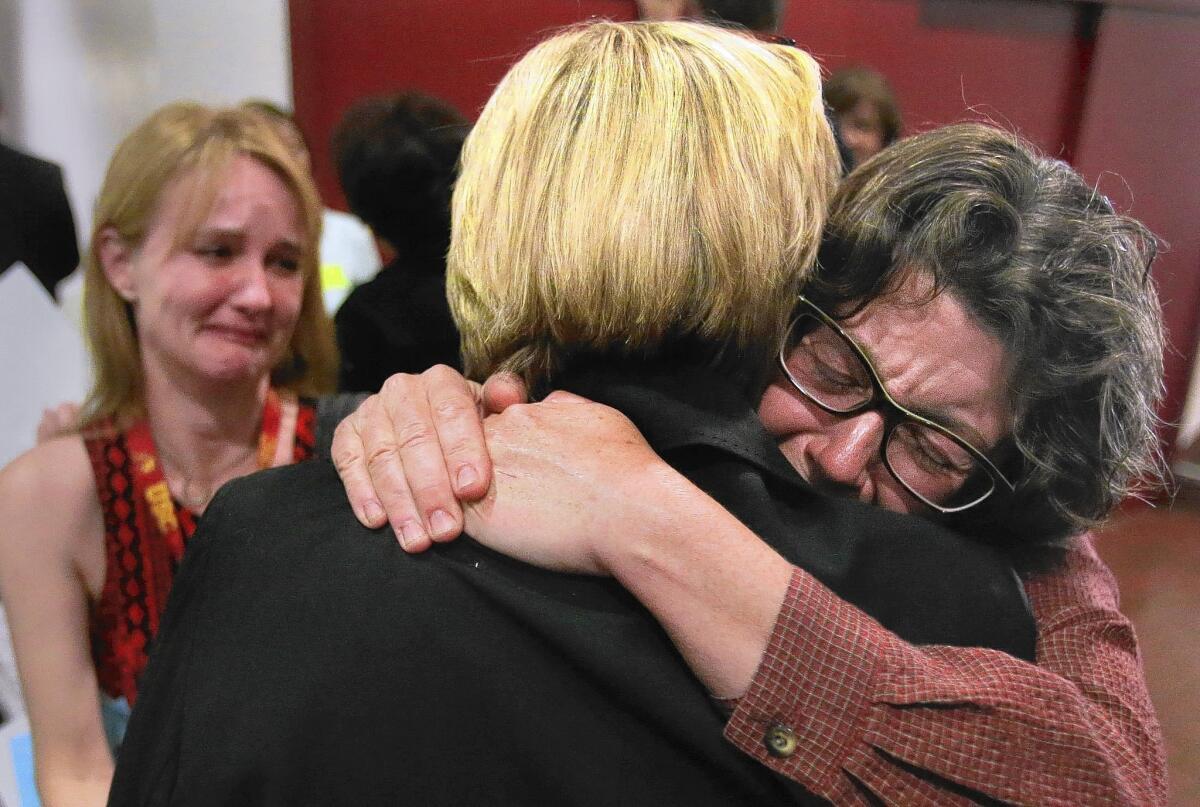

The stakes are high, as testimony at a recent committee hearing revealed.

Dale Milfay carries copies of her son’s driver’s license photo in her wallet, his identifying information snipped off to protect his privacy. She shows his face to anyone willing to look. He has suffered 79 psychotic incidents, each one making recovery a more remote prospect. He has racked up $1 million in public healthcare bills. He’s never been able to stick with his treatment plan.

“It may be too late for my son,” she tells the committee as she pleads for program approval, saying it will “take nothing away from anyone capable of accessing voluntary treatment.”

Sgt. Kelly Kruger, San Francisco Police Department psychiatric liaison, comes to the microphone to discuss her previous week. One woman who had “terrorized” her residential hotel was gone by the time police arrived — hospitalized on an involuntary psychiatric hold for the 12th time in 2 1/2 months. But the woman “can clear up very quickly,” Kruger explained, so she cycles right back out. Now she is being evicted and will be homeless.

When Kruger describes a second case, she begins to cry. A woman who had given birth on the street — possibly as the result of sexual assault — had bound her own legs in speaker cord, presumably to protect herself, and then defecated and urinated.

“I can’t see how we’re doing a service to a person like that,” Kruger says. “I don’t see how that’s humane.”

Wilcox’s parents are there too. They have attended these hearings for years. Nick Wilcox shares Nevada County’s statistics: More than half of those court-ordered into treatment have signed voluntary settlement agreements to participate, although he noted that the “black robe effect” probably keeps them engaged. Since 2008, hospitalizations are down 64%, incarceration 27% and homelessness 33%, according to the a county report.

Opponents from the Mental Health Assn. of San Francisco pack the hearing room, their matching shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Force is the Opposite of Treatment. Demand Dignity Now.”

Cynthia Crews shakes with anger and weeps. “Eleven years ago you would not know me as the high-functioning activist I am today because I sat hospitalized, drooling,” she tells the committee. “We have rights as individuals to choose what happens to our own bodies.”

If she had been forced to follow the hospital’s medication regimen, Crews says, “I wouldn’t have gotten better.” Instead, “I sought treatment on my own terms and got my meds right.”

Failure to comply with court-ordered treatment is not cause for involuntary commitment or contempt of court under Laura’s Law. But David Elliott Lewis, co-chairman of San Francisco’s mental health board, points out that the judge can order a psychiatric reevaluation, and if refused the person would be transported to the hospital “in handcuffs. And that is coercion.”

After the hearing he says that many people too ill to attend the hearing, many already wary of the mental health system, would be further deterred from seeking help if Laura’s Law is implemented. Instead, he says, more money should go to rebuild a decimated community treatment system, to reduce wait times for appointments.

“In this room are all these natural allies,” he says. “We all want better care. How do we do that while causing the least damage?”

The full board will decide.

Twitter: @leeromney

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)