How do you prosecute a murder without a body? California has been doing it for more than a century

- Share via

The recent discovery of 5-year-old Aramazd Andressian Jr.’s remains at a Santa Barbara recreation area was a grim achievement for investigators who had spent more than two months frantically searching for the boy.

It was also a boost for Los Angeles County prosecutors, who had already filed a murder charge against the child’s father without having found the body.

Authorities have not released details about the condition of the boy’s remains, but the discovery can only help investigators as they try to piece together what exactly led to his death.

Pursuing a murder case without having found a victim’s body presents a unique challenge for prosecutors. Lacking a corpse means they can’t show jurors the type of powerful evidence that proves someone was beaten to death rather than killed in an accident — or tortured rather than slain in self-defense.

“In a murder case, the body is the most significant piece of evidence,” said Tad DiBiase, a former assistant U.S. attorney who consults for law enforcement on “no body” homicide cases.

Days before the boy’s remains were found, Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey said she was confident about the decision to file a murder charge against Aramazd Andressian Sr.

Her office, she noted, has handled several “no body” cases with success. Four years ago, for example, a Los Angeles County jury convicted Lyle Stanford Herring for the second-degree murder of his wife, who went missing four years earlier.

And just last month, Hector Veloz, 46, was charged with killing his wife, Sandra Velasco, 52, after meeting her on June 18 at a storage unit in the San Fernando Valley, according to prosecutors. Her body has not been found.

Indeed, prosecutors in a similar position can take heart from a successful track record of winning “no body” murder cases in California that goes back more than 100 years. In 1879, two brothers in Monterey County were convicted of setting a man on fire and stealing his sheep, according to a list of such cases compiled by DiBiase.

Here are some other notable California “no body” trials through the years:

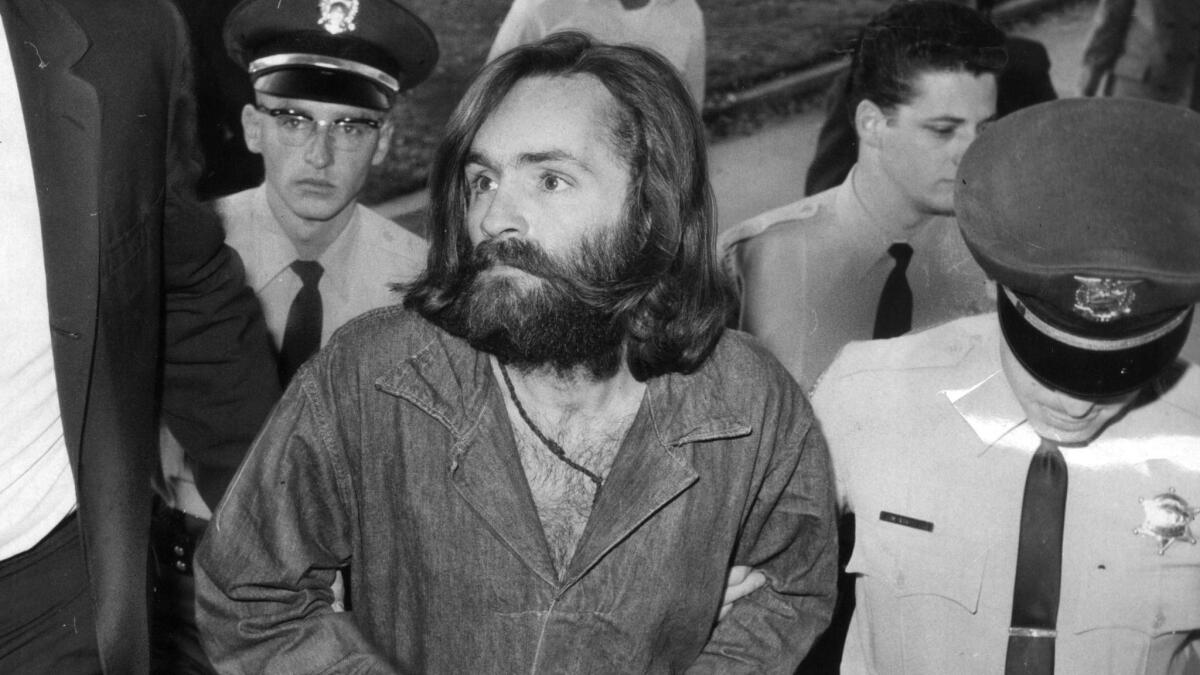

1969

Donald ‘Shorty’ Shea, 35

Although

Shea was described by The Times as a “husky bouncer, horse wrangler and Western character actor.” Manson didn’t get along with him because Shea was married to a black woman and Manson suspected he was to blame for a police raid on the Spahn movie ranch, a Manson hangout.

Shea’s wife, Magdalene, told authorities that when she went to the Spahn ranch to look for her husband, she was told he had gone to San Francisco.

Detectives believed that Shea was hit on the head at the ranch and driven via dune buggy to a remote spot, where he was stabbed and eventually beheaded.

A witness testified that Manson boasted he had cut Shea up into nine pieces and buried him under some leaves. And Shea’s wife testified that her husband would not just disappear because he had a good chance of landing a speaking part in a movie.

Manson and two members of the “Manson Family,” Steve Grogan and Bruce McGregor Davis, were eventually convicted in Shea’s killing. Years later, Grogan led authorities to Shea’s body in exchange for parole.

April 1991

Ann Mineko Racz, 42

Ann Racz was so meticulous that when she would go on vacation, she would pre-address mailing labels beforehand so she could send postcards to friends back home.

So when she went missing days after moving out of the Valencia home she shared with her husband, her friends and family were immediately suspicious. Racz’s abandoned car was found at a Van Nuys airport shuttle parking lot.

Fifteen years after the woman went missing, her husband, former Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Sgt. John Racz, was charged with her murder. He told investigators he had met his wife and spoken to her several times after her disappearance, but investigators were not able to corroborate his statements. A friend testified at trial that Ann Racz was “scared to death of her husband.”

Their eldest child testified during the trial, saying she suspected her father in the killing, according to news reports at the time.

Deputy Dist. Attys. John Lewin and Beth Silverman relied on circumstantial evidence to convince jurors of Racz’ guilt.

“Whether you have a body or not, it’s clear she’s dead,” Lewin said in 2007, after John Racz was convicted of murder.

July 1997

Pegye Bechler, 38

In the summer of 1997, Pegye Bechler was with her husband off the coast of Newport Beach when she disappeared.

Eric Christopher Bechler said Pegye was driving a power boat that was pulling him on a bodyboard when a wave sent him tumbling underwater. When he came to the surface, he saw the boat circling in the distance with his wife — a strong swimmer and triathlete — gone.

At first, authorities thought it was a tragic accident; but more than three years after the woman disappeared, her husband was charged and eventually convicted of murder.

Prosecutors said that Eric Bechler had bludgeoned his wife to death so he could cash in on a $2-million life insurance policy. A former “Baywatch” actress and model testified that Bechler admitted anchoring his wife’s body with 70 pounds and throwing her overboard.

The woman, Tina New, secretly wore a wire during a dinner date, where Bechler admitted killing his wife “partly for the money, partly for the kids.” Bechler was sentenced to life in prison.

September 1999

Jack Irwin, 71

Months before Jack Irwin, a Korean War veteran, went missing, he made two new friends. Marcia Ann Johnson and her partner, Judy Gellert, persuaded Irwin to add them to his trust and give them access to his bank accounts.

Johnson told authorities that she shot Irwin in the head at his Mt. Baldy cabin because he had repeatedly exposed himself to her and made disparaging comments about Gellert. Johnson then cut off Irwin’s head, feet and hands with a chain saw, loaded his body into her SUV, then stopped along Mt. Baldy Road, dropping body parts off at various locations.

When she disposed of Irwin’s head, she took it out of a plastic bag and rolled it down a hill, yelling at it for “making me do this to him,” she told authorities in a videotaped statement.

Gellert struck a plea bargain in exchange for testimony against Johnson, who was convicted of first-degree murder in 2004. Gellert was sentenced to 180 days in jail and five years’ probation, and was ordered to pay $150,000 in restitution. Johnson was sentenced to life in prison.

February 2001

Katrina Montgomery, 20

Katrina Montgomery, a Santa Monica College student, disappeared on Nov. 28, 1992, after leaving a party in Oxnard. Her bloodstained blue pickup truck was found abandoned in the Angeles National Forest near Sylmar the next day, but her body was never found.

It took six years for detectives to build a murder case against Justin Merriman, a skinhead gang member.

Prosecutors said that when Montgomery spurned Merriman’s sexual advances, he raped her, stabbed her in the neck and beat her with a wrench to prevent her from reporting the sexual assault to police.

Two other San Fernando Valley skinhead gang members witnessed the attack but testified that they had initially been too scared to speak up. Merriman was convicted and later sentenced to death in 2001.

For more news on homicides in Los Angeles County, follow me on Twitter: @nicolesantacruz

ALSO

Another longtime lawman joins race for L.A. County sheriff

Nadia Lockyer, wife of former California attorney general, is arrested in domestic dispute

Former guard pleads guilty to smuggling drugs and phones into San Diego prison

UPDATES:

1:17 p.m.: This article was updated with the name of an additional prosecutor on the Ann Racz case.

This article was originally published at 4 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.