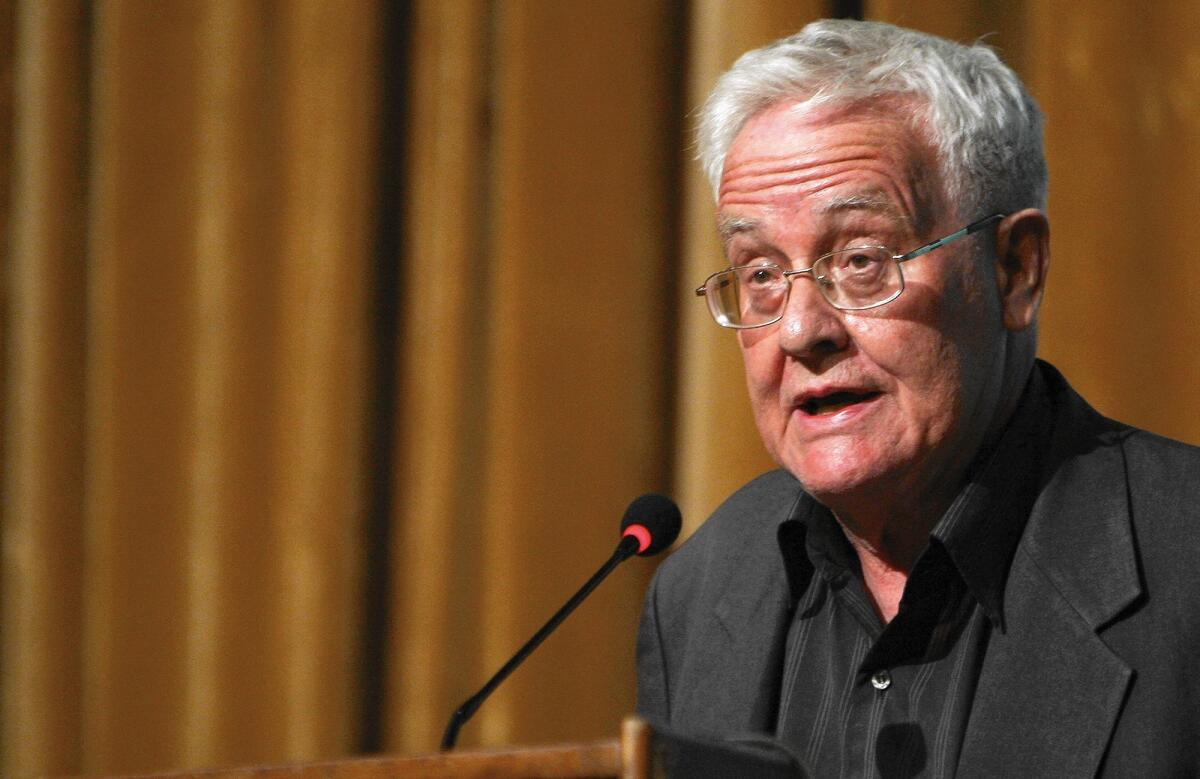

Benedict Anderson dies at 79; Southeast Asia scholar studied roots of nationalism

Benedict Anderson in 2009. His 1983 book “Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism” remains a touchstone across multiple disciplines.

You know what you are doing to this newspaper; you are reading it.

But do you know what this newspaper is doing to you?

Southeast Asia scholar Benedict Anderson argued that reading a newspaper was not just a pastime. It was the making of a new order by means of a powerful technology.

Along with maps, schools, health services, museums and other trappings of modernity, newspapers lead people to adopt shared national identities, he said — even if it means identifying with strangers miles away. Newspapers, in short, helped explain nations.

That nations needed explaining — a novel proposition in itself — was the kind of insight for which Anderson was known. Nations may seem normal. But Anderson saw them as new and weird — “the shrunken imaginings of recent history,” he wrote.

Anderson, who spent part of his childhood in Los Gatos, Calif., and gained eminence for both the range and quality of his scholarship — as well as his unwavering criticism of the Suharto regime in Indonesia — died Dec. 13 in the city of Malang, Indonesia. He was 79.

He is best known for his 1983 book “Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism,” which examines how nationalism is constructed, and why it’s so passionately embraced.

More than three decades after its publication, the book remains a touchstone. In recent months, analysts have invoked it to explain countries as diverse as Ireland, Russia, Syria and Nigeria, as well as the rise of the Islamic State.

Anderson also co-wrote a highly influential paper critical of Suharto’s brutal seizure of power in 1965 and 1966 — at least 500,000 people were killed. The paper got him banned from Indonesia for three decades.

But it was seized on by Indonesia’s democracy movement, and Suharto was ousted in 1998. In Indonesia, Anderson’s death has been treated by many as a public loss. “He was one of a few American scholars who really just dished it out to the Suharto regime…and he suffered for it,” said David Biggs, a Southeast Asia scholar at UC Riverside. “People respect him for that.”

In this country, Anderson figured large mainly among scholars. The young professors he trained at Cornell University include several now in California.

Anderson was seen as a leading scholar of post-colonial theorists on the left, and his assertions drew fiery rebuttals.

But the depth and complexity of his arguments, and his expertise with languages, made it difficult for opponents to dismiss him. “Imagined Communities” remains a staple text, assigned to graduate students across disciplines.

Anderson drew lofty ideas from low places. He combed obscure government registers, shipping news, songs and poems. He grounded sweeping theoretical assertions in the arcana of everyday life — a postcard, a piece of classroom art, a colonial officer’s collection of relics.

“He was really a Renaissance man,” said Geoffrey Robinson, UCLA history professor and former Anderson student. “If you went to one of his talks, you never knew if it would be a straight academic talk or a reflection on Thai kung fu.”

Colleagues were astounded by his linguistic skills, which the New Republic called “superhuman.” After he was blacklisted in Indonesia, he learned Thai, Spanish and Tagalog, and became a respected authority on Thailand and the Philippines.

“The most brilliant guy I ever met,” said Peter Zinoman, UC Berkeley history professor and another former Anderson student. He called Anderson “a magician.”

Benedict O’Gorman Anderson was born in 1936 in Kunming, China, the son of an Anglo-Irish Chinese Maritime Customs employee and an English mother. The family left during World War ll and settled in Los Gatos. Anderson became a scholarship student at Eton, graduated from Cambridge University with a classics degree and went to Cornell in 1958, according to his sister, Melanie Anderson.

Anderson first traveled to Indonesia in 1961 for his dissertation. Suharto rose to power just a few years later, bolstered by claims of an attempted Communist coup. Anderson’s famous Cornell paper, written with Ruth McVey, sought to debunk those claims.

Despite being blacklisted in Indonesia, Anderson remained deeply committed to the country. He said he often thought in Indonesian. He adopted two Javanese sons.

The nationalism that arose from anti-colonial forces in Indonesia struck him as puzzling. It didn’t seem born of ethnic loyalties or fascist ambition. How had hundreds of ethnic groups across thousands of islands stitched themselves together?

Anderson came to see what he called “nation-ness” as a surprising, distinctly modern and potentially favorable turn of events. Somehow, people took a kind of collective imaginative leap. Lots of factors prompted them to do so, not least the institutional footprints of colonialism — land surveys, censuses, common vernacular languages.

Print capitalism, epitomized by newspapers, was especially important. “You have to understand the novelty of the morning paper. All these people get up at the same time … and identify with the child who fell down a well,” Zinoman said. At some point, they become willing to die for an abstraction similar to that which links them to the child.

Nationalism was not an ideology like fascism, Anderson argued. It was merely another kind of community, a twist on the theme of village or kinship network. It was a cultural artifact manufactured by various state and market processes — some conscious, some not.

Crucially, he argued that these processes were “modular,” meaning they could be replicated all over the world. Thus, nation-ness was catching. And a nation-ized world would probably have staying power, he suggested — which so far it has.

Described as shy and gruff, Anderson had an ambiguous accent that reflected three continents. He was an exacting teacher.

Robinson recalled trying to enlist his help in avoiding a statistics course. Anderson would have none of it. “Once you have done that course and gotten an A, you have earned the right to criticize it,” he told Robinson.

“He was a model of the idea that class should be scary,” Zinoman said. “There is something incredibly productive about being afraid … you would prepare so much. When you went to seminar, your adrenaline would be pumping.”

Beneath it, said Robinson, Anderson was kind. “Indonesians would come and visit Cornell. They were freezing cold. They didn’t have any friends,” he said. Anderson “would always have them stay at his house.”

Besides his sister, Anderson is survived by his brother, Perry Anderson, a UCLA history professor, sons Yudi and Beni, and niece Louisa.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.