Fewer high school students are applying for college aid under the California Dream Act

- Share via

Fears about heightened enforcement of federal immigration laws combined with confusion and anti-immigrant rhetoric might be causing thousands of California students who came to the United States without legal papers to forgo valuable college aid.

Far fewer students than last year have applied for financial aid through the California Dream Act so far this year, and advocates are trying to encourage them to do so before the March 2 deadline.

On Tuesday, the California Department of Education published a letter urging students to apply, and promised to protect student information to “the fullest extent of the law.”

Several California Assembly members announced a resolution designed to get the word out and encourage applicants. “Please fill out your forms, plan for college,” Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Paramount) said in a news conference Wednesday. State Sen. Ricardo Lara, a Democrat who represents Long Beach, has introduced a bill that would allow a broader pool of students to apply.

The California Dream Act allows students who are in the U.S. illegally to apply for the same financial aid packages available to others.

These packages, known as Cal Grants, can give students up to $12,294 per year, depending on their grades and the colleges they wish to attend. The money can go toward tuition and other costs at state community colleges, California State University, the University of California and accredited private colleges.

Officials believe that students are applying in lower numbers because they’re scared of being identified as lacking legal status in the current climate, when their news feeds are full of stories about Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids.

“I believe that students are not filing because they’re afraid to file,” said Lupita Cortez Alcalá, executive director of the California Student Aid Commission, the organization that administers state financial aid.

The drop in applications is even more striking considering that the commission recently made changes to give students more time to apply. Last year, students only had from January through March 2 to submit requests for college aid. During that period, 13,200 students filed for first-time Dream Act grants, and 20,962 asked to renew their funding.

This year, officials opened up applications for Dream Act and other scholarships in October. But as of Feb. 17, only 8,668 students had applied for new grants, and 11,429 had applied for renewals.

The Trump administration has yet to take action to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the protections instituted by President Obama that allow hundreds of thousands of immigrants who entered the country illegally as children to live and work openly in the U.S.

But on Tuesday, the Department of Homeland Security released new guidelines that empower immigration enforcement officers to target any of the 11 million people in the U.S. illegally. The memos called for hiring thousands more agents but did not say how officers should handle the so-called Dreamers.

California officials have repeatedly assured students that the state would keep their personal information safe. But students might not draw a distinction between the state and federal governments, and even the staunchest of advocates don’t know for certain how far federal enforcers might go to get their hands on state files.

“I hope we’re right in encouraging students to go to college,” said Jane Slater, a college counselor at Sequoia High School in Redwood City, Calif., where she estimates 1 in 5 students are undocumented. “Everyone at the school is saying you should apply, which hopefully doesn’t come to bite us.”

Worries are equally intense elsewhere. “There’s a big fear of the unknown and the worst of all possible actions: fear of families being torn apart and not being able to go to school,” said Heather Hodgson, a counselor at Compton High School.

Cortez Alcalá said she has heard plenty of such concerns from students and families.

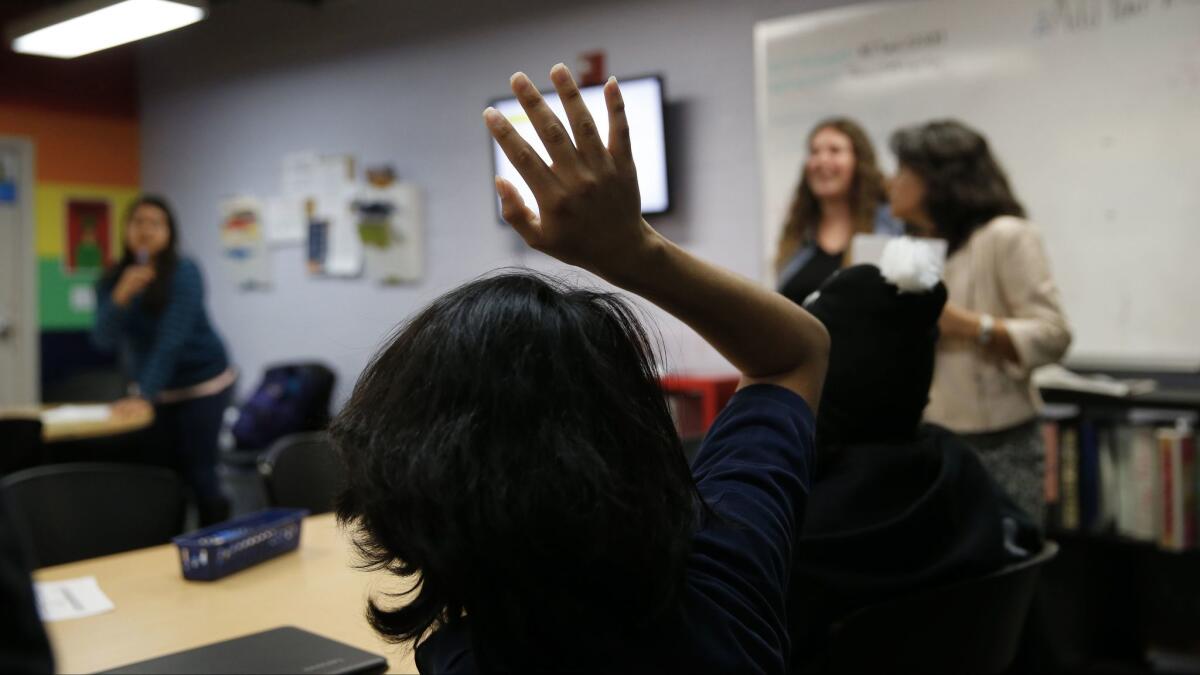

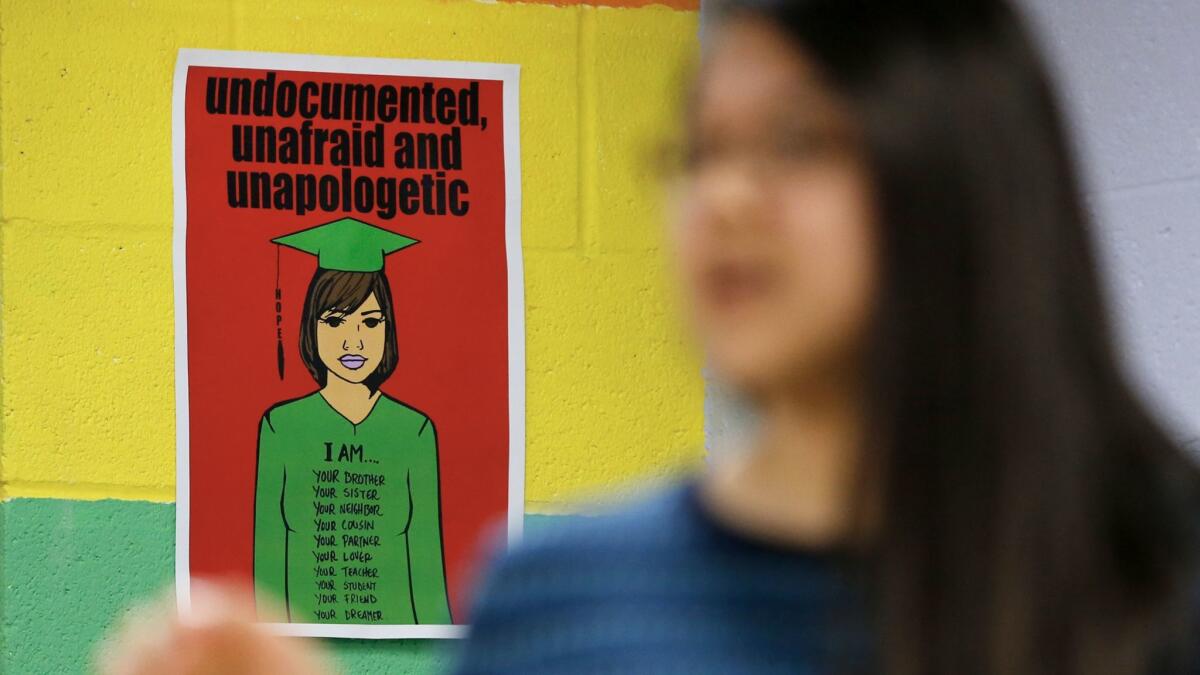

On a recent afternoon, students from two public schools in downtown L.A. buzzed about Kid City, a brightly painted after-school space that helps immigrant students plan for college. The walls prominently displayed “Know your rights” bulletins.

One high school senior who gave his name only as J out of fear of being identified said he wanted to be an engineer. “I never thought I’d have the opportunity to think about college,” he said. “There are statistics about minorities not going to school, and putting your name out there with the label of undocumented is risky.”

He said his mother brought him to the U.S. when he was a toddler, and he doesn’t know his father. Kid City staff helped him fill out the Dream Act application, but he was nervous about it. “A lot of kids think that their information would be disclosed to ICE,” he said. “If we’re deported, I’d be back in Mexico, even though I have no memory of the place.”

Another senior who moved to the U.S. from Puebla, Mexico, when she was 6 said she at first struggled in school and worked to teach herself English from picture books she borrowed from the library. Her brother, who was born in the U.S., has spina bifida. She, too, filled out the Dream Act application, but she said she understood why others might not want to.

If her parents got deported, she said, as she started to cry, her brother wouldn’t have anyone to take him to his medical appointments.

She wants to attend Cal State Long Beach or Cal State Fullerton and become a journalist one day.

David Marks, a college counselor at Sacramento Charter High School, said the current climate is particularly rough on those young people who fully understand what they stand to lose: “They feel like promises are being ripped out from under them.”

Staff writer Melanie Mason contributed reporting.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

Trump administration clears the way for far more deportations

Will the U.S. punish Mexico on trade? A Trump supporter has doubts

Trump’s top deputies hope to shore up ties with a suspicious Mexico

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.