Merced, the least renowned of UC’s campuses, is attracting more students and rising in the rankings

- Share via

Reporting from Merced — Gabriel Picazo applied to only one University of California campus — and not the one his family and friends expected.

The 20-year-old from Long Beach chose UC Merced — the youngest, smallest and least renowned of the UC system’s nine undergraduate campuses. It is far from bustling urban centers, located in a flat expanse of grazing land that it shares with cows.

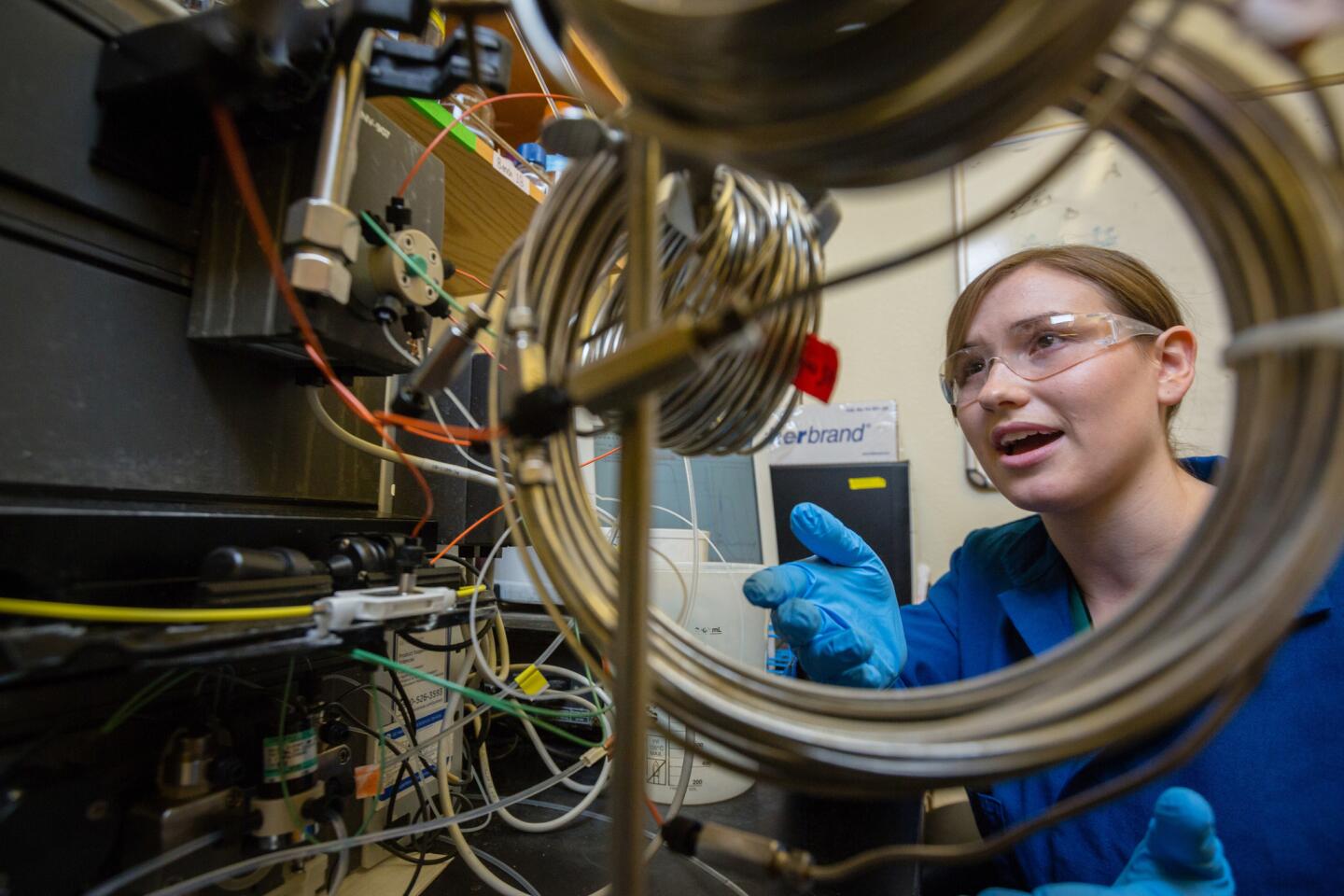

But Merced had what the aspiring engineer wanted: a focus on sustainability, with cutting-edge research and ambitious conservation goals.

“Deep in my heart, I wanted to go to UC Merced because everything you heard about it was that it was going green,” Picazo said.

Eleven years after opening its doors as the first new American research university of the 21st century, UC Merced is attracting more students, winning research accolades, rising in national rankings — and moving forward with an ambitious campus expansion.

The progress was celebrated Friday when UC officials broke ground on the construction, which will more than double the size of the campus, from 104 to 219 acres, allowing it to accommodate about 10,000 students by 2020. The $1.3-billion project will include new student housing, research labs, a dining hall, a pool and fitness facilities.

UC President Janet Napolitano, Board of Regents Chairwoman Monica Lozano, UC Merced Chancellor Dorothy Leland and four students did the official honors, scooping up dirt with golden shovels against a backdrop of a bulldozer and blue-and-gold UC flags.

“We’re coming of age in a remarkably quick period of time,” Leland said in an interview.

She said she was most proud of progress in the rising graduation rate of the students, the majority of whom are low-income, underrepresented minorities and the first in their families to attend college. Though UC Merced’s six-year graduation rate of 67% still is the lowest among UC campuses, it is higher than predicted for students with the school’s demographics and was one reason the campus landed for the first time this year on U.S. News & World Report’s list of top national universities.

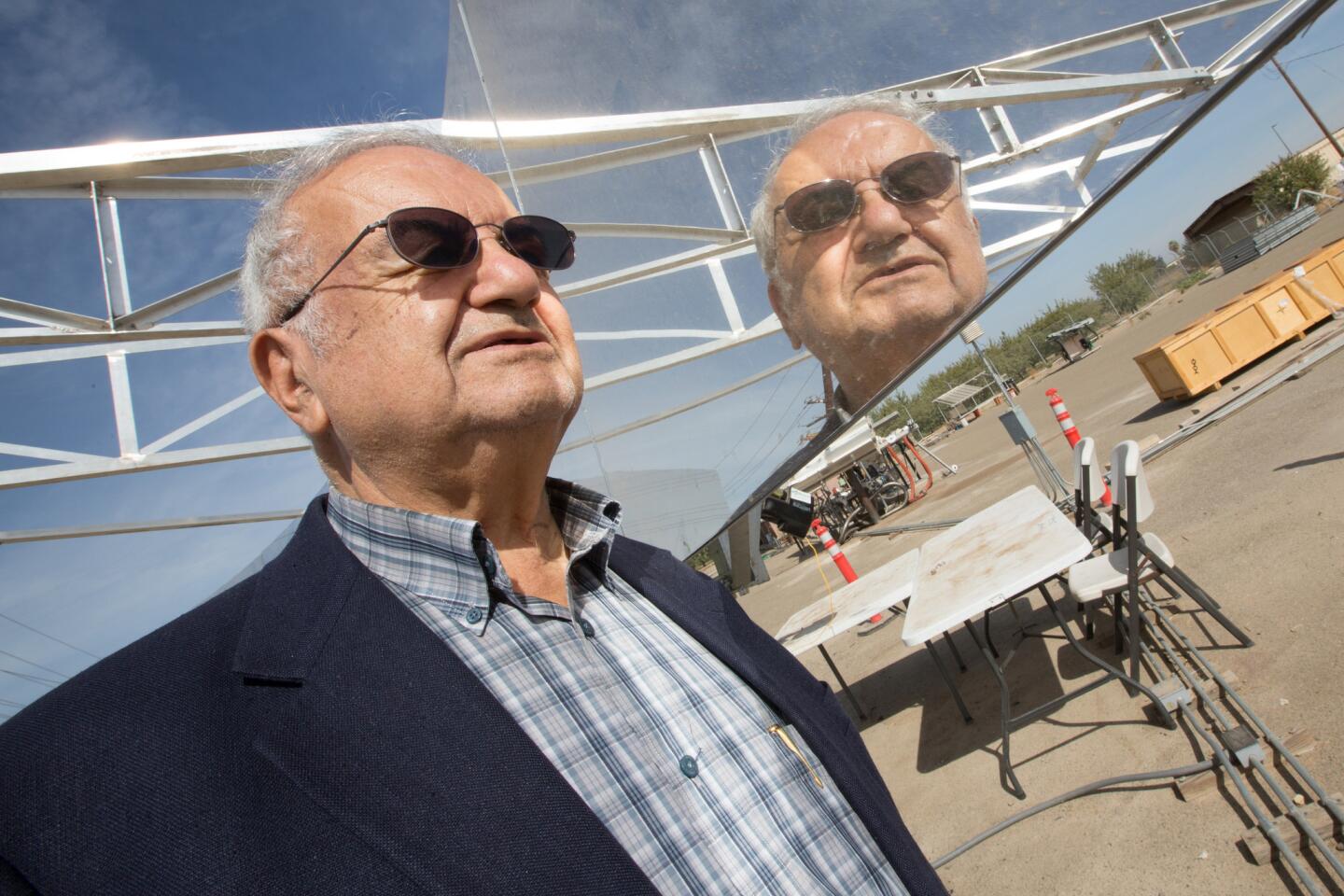

Leland spoke of the faculty’s achievements in research, recognized this year in the Carnegie Classification, a national review. The campus has attracted strong faculty, she said, including Roland Winston, who came to sunny Merced from the University of Chicago for the chance to perfect a solar technology that is now being installed in China, Mongolia and other far-flung places. Winston is now the director of UC Solar, which has all the UC campuses involved in researching ways to make solar energy more efficient and affordable.

The recent accolades have created positive buzz about UC Merced, long the campus of last resort for students rejected at their preferred UC choices. The system guarantees a spot for all Californians who meet UC eligibility requirements — a 3.0 grade-point average and completion of a series of college-level courses called A-G — and Merced has been the only campus with room for those who don’t get in elsewhere.

But the percentage of such “referred” students dropped to just 8% this fall compared with 28% in 2005. Leland said the campus could have filled its entire incoming class with those who voluntarily selected Merced, but it over-enrolled students this year to honor the UC guarantee.

As a result, the campus admitted about 2,200 freshmen and transfer students, squeezing them into dorms designed for 1,800. To make room, university officials leased off-campus housing for 450 students and converted double rooms into triples and triples into quads.

“We have an acute need to grow,” said Daniel Feitelberg, Merced’s vice chancellor for planning and budget.

The 2020 project will help ease that crunch, with 1,700 additional beds expected to be ready in two years. The university signed a 39-year contract with the private development consortium Plenary Properties Merced to maintain major building operations at an annual cost of about $10 million. Though some faculty members questioned the move to a private contractor, Feitelberg said it would provide an incentive to build top-quality buildings, delivered on time — or face reduced payments.

The expansion project, in the works for four years, will build on Merced’s environmental commitments to consume no net energy and produce no net trash or greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. As with all of the current buildings, the new ones will be constructed with some recycled material, such as Coke bottles and newspapers, and be cooled with pipes filled with chilled water, which are more energy-efficient than traditional air conditioning systems.

At a VIP luncheon Friday, Merced city and county officials said the project would prove a boon to the San Joaquin Valley, where poverty and unemployment rates are among the state’s highest. The project is expected to create 2,500 jobs over four years and $1.9 billion in one-time economic benefits, officials say.

“It will be transformative,” said Hubert “Hub” Walsh, chairman of the Merced County Board of Supervisors. UC Merced, he said, already has raised the college ambitions of area youths and created rich opportunities for residents, such as a recent visit by NASA officials.

But not everyone shared the boosterism. The groundbreaking was interrupted by several student protesters, who called for “dignity and respect” and distributed written demands for a cultural resource center, more diverse faculty, ethnic study courses and a halt in enrollment growth until current student needs were met.

Katelyn Fitzgerald, UC Merced student body president, said those needs included housing, food security and mental health resources. She also said that she and other students felt their voices had not been adequately included in the planning process.

“There’s a huge disconnect” between students and administrators, Fitzgerald said. “Why isn’t the university focusing on these issues before we grow more?”

UC Merced spokesman James Leonard said the university was proud of the resources and support devoted to students from disadvantaged backgrounds and planned to increase that aid as the campus grows.

Several students said the new facilities would add more luster to a campus they had grown to love, despite initial misgivings among some.

Jalen Siler, a senior from Compton, said he cried when his father told him he would not take out loans to send him to his dream school, Syracuse University, when UC Merced was offering a free ride. But Siler said he found that the small campus offered a rich array of leadership opportunities. There, he could be a judge in student conduct cases, a fraternity leader. The new buildings, he said, will be another selling point when he pitches the campus to his friends back home, as he now does.

Jessica Rivas, a senior from North Hollywood, mistakenly thought that UC Merced was in Santa Cruz; after arriving on campus in “the middle of nowhere,” she was determined to transfer as soon as she could. But she quickly changed her mind after joining a student leadership program Merced runs with Yosemite National Park, an experience that has shaped her desire for a career in wilderness education.

Adam Delong, a Sacramento freshman, said he chose UC Merced over UC Santa Cruz because he heard about great research opportunities for undergraduates, which on more elite campuses require an “Olympian” effort to land. He hopes to do stem cell research, possibly in one of the new labs.

His one fear about the expansion is that it might jeopardize one of UC Merced’s best features: its small size, which engenders close friendships and teamwork.

“People generally want to head in the same direction together,” he said, “and that’s what I’m afraid will disappear with the 2020 plan.”

ALSO

Parents who want their kids in L.A.’s most competitive magnet schools face daunting odds

What you need to know about the $9-billion school bond on the ballot

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.