Great Read: Evidence may be sketchy, but not this courtroom artist’s drawings

- Share via

Mona Shafer Edwards stepped through the doors of a downtown Los Angeles courtroom, striding past the bailiff, the defense attorney and prosecutors to a seat in the jury box.

She removed a Ziploc bag bulging with pens and markers from her Gucci purse and propped a sketch pad on her lap.

“You made me look really old,” Judge Ronald S. Coen deadpanned from the bench. “But you got the cleft chin right.”

“I’m sorry,” Edwards said, laughing. “I’ll do better.”

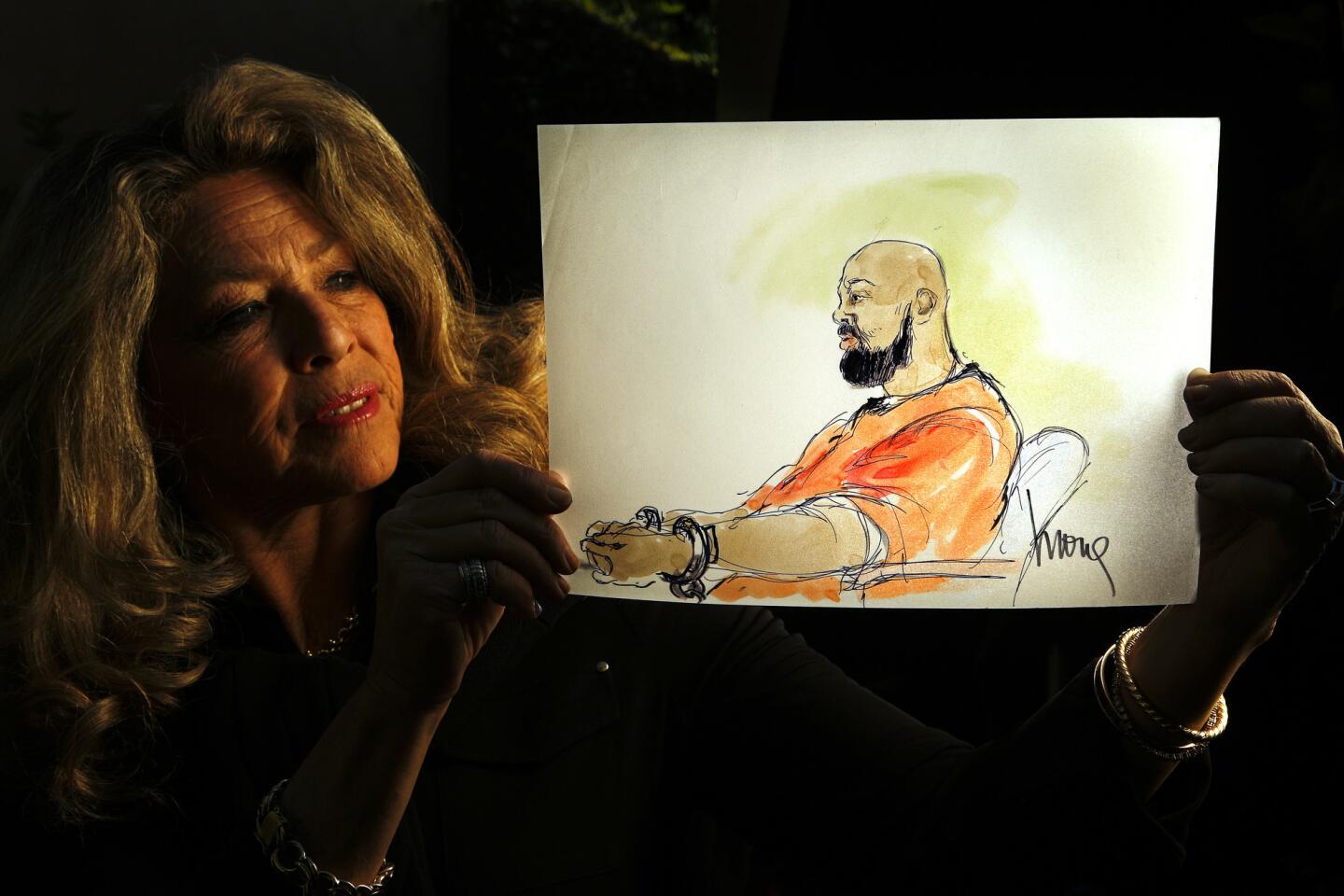

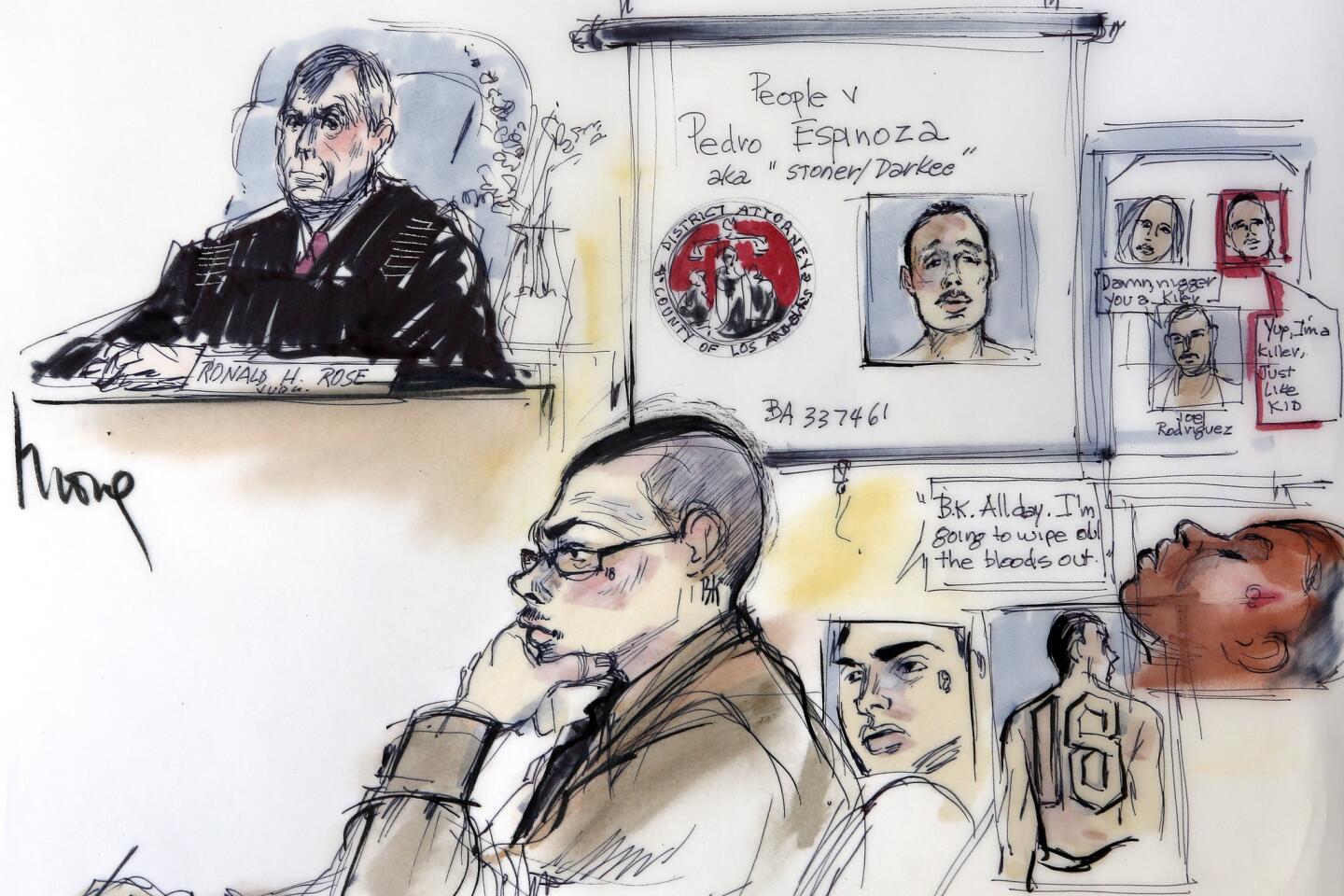

Her pen darted over the page as Marion “Suge” Knight, a former rap mogul who now faces a murder charge, shuffled into the room. Bold strokes traced his scowl and handcuffed hands, the slouch of a detective on the witness stand, the dent in the judge’s chin.

The courtrooms of Los Angeles are where the dramas of L.A.’s rich and famous play out, and for three decades Edwards has been there for some of the wildest. Pens and markers in hand — she never uses pencil, and she never erases — Edwards has captured the emptiness in the eyes of “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez, the unsmiling face of O.J. Simpson and the ever-changing features of Michael Jackson.

She is among the few remaining sketch artists working today, fusing journalism and art to illustrate the theatrics and emotion of the courtroom. It is a skill that has managed to survive the introduction of photography and video, finding a home in courtrooms where those images are banned, or with judges weary of the distraction that the news media can bring.

As the Knight hearing ended, Edwards dashed outside to put the finishing touches on the sketches. Knight’s jailhouse scrubs bloomed orange with a smear of marker, and each was finished with “Mona” signed in black.

As Knight’s attorney held an impromptu news conference, Edwards taped the sketches onto a wall and the cameramen whose stations had paid for the images soon lined up single file, taking turns shooting close-ups as Edwards shooed away non-paying onlookers hoping to sneak a cellphone photo.

Knight’s lawyer, Matthew Fletcher, wandered over for a look at himself.

“Oh, man…,” he said, rubbing the bald head depicted in the sketch.

::

The sketches that flashed across the 10 o’clock news caught Edwards’ eye — for their lack of movement, artistry and flair.

“They were awful, just awful,” she said. “I told my husband, ‘That’s what I want to do. I can do that.’”

Edwards had been working for years as a fashion illustrator, hired by design houses and department stores and teaching at colleges around Los Angeles. She saw that her skills in fashion could translate to the courtroom.

She went to one station and showed the art director her illustrations. “He told me ‘You should stick with fashion,’” Edwards said.

Next was KNBC, which gave her a shot, sending her to the soon-to-be-infamous “palimony” trial of actor Lee Marvin in 1979.

In those days, each local news station had its own artist, and the networks flew in their own for big cases. At the Marvin trial, she met Bill Robles, who is now the only other remaining sketch artist in Los Angeles and a friendly rival.

Over the years, there have been disagreements and the occasional jostling for prime seats in the courtroom, Robles said.

“There’s competition, but it goes with the territory,” he said. “We’re professionals and we always get the image.”

The two have worked alongside each other for decades, surviving all their counterparts who left the business, either by choice or lack of work.

Edwards, a freelancer, was reluctant to say what she charges media outlets for her drawings. But she said no matter the case, the process is always the same.

She first finds a feature that is prominent — anything from a hair style to lips or a nose. Then she scopes out the person’s body language, his posture and how his clothes fit. Then she draws the image in her mind, plans it out and starts the sketch.

“Before pen touches paper, I mentally complete the work,” she said.

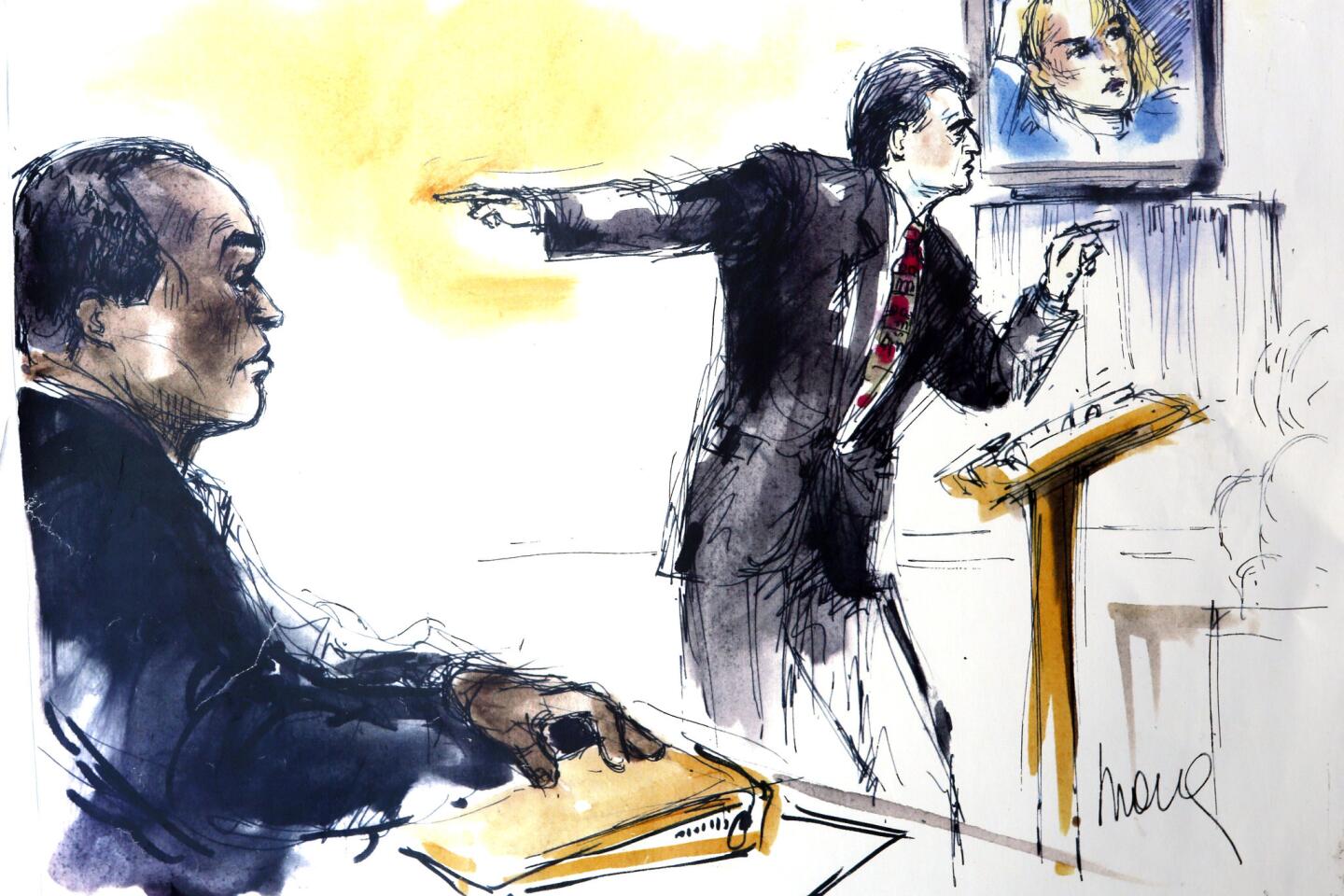

The key is to capture the person’s spirit, to draw more than a mere portrait. It is up to her to do what a camera cannot, which is to capture the humanity in the room with a human’s touch, she said.

“The cold eye of the camera doesn’t pick up the essence of the story unfolding before you,” she said. “A camera doesn’t capture the soul.”

::

The killer known as the Night Stalker sat defiantly in a downtown Los Angeles courtroom. A few feet away sat Edwards, with her pen and pad.

She heard testimony of how he entered homes through open windows and shot, strangled, stabbed and raped his victims. She tried to capture his menacing stare and the terror he brought to all of California in the summer of 1985.

Then Ramirez turned to Edwards and offered a toothy smile.

“He was pure evil,” she said. “His eyes pierced me and my blood ran cold.”

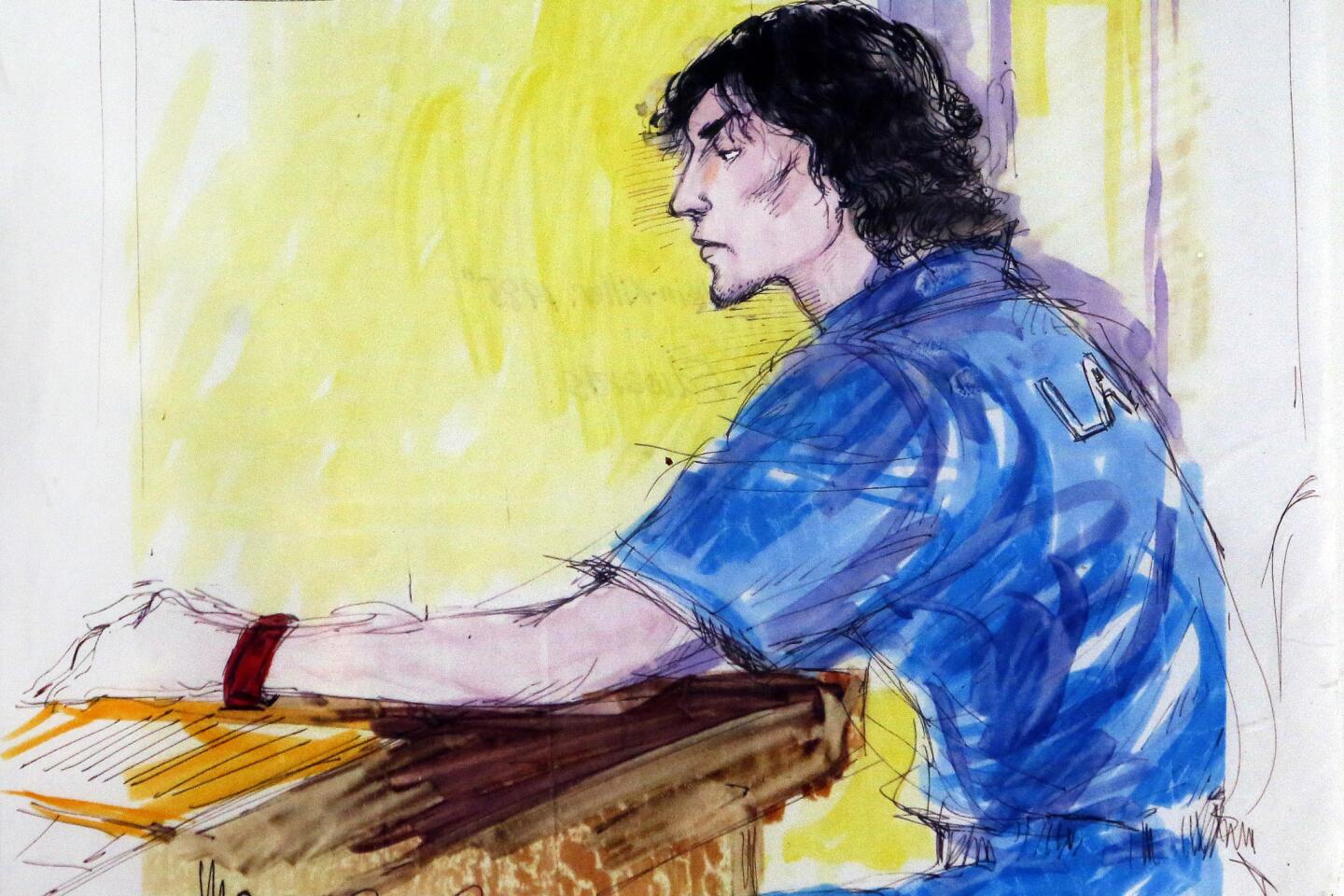

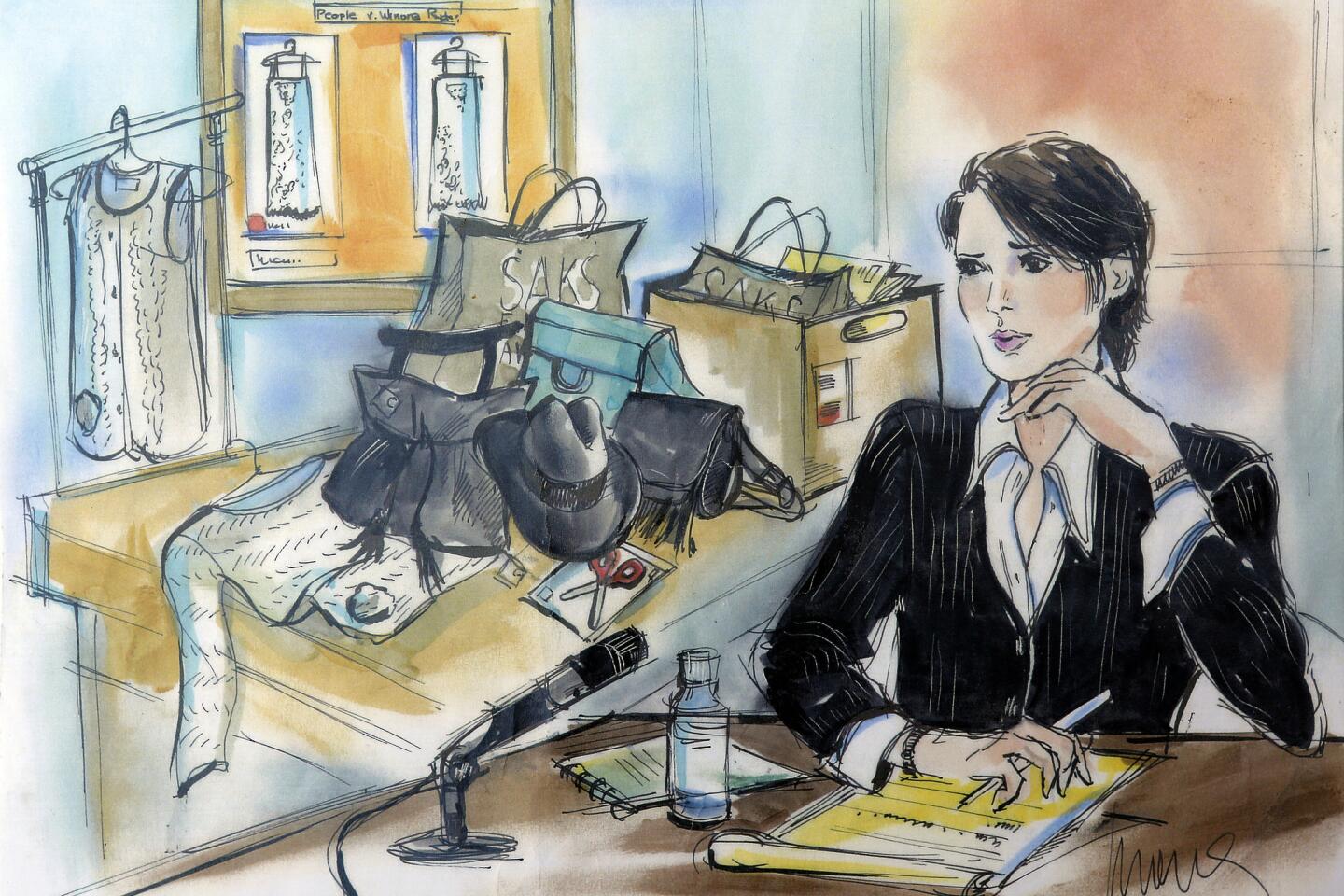

Edwards’ sketches are a who’s who of notorious Los Angeles trials. There was the 1980s McMartin preschool child molestation case, one of the longest and costliest trials ever, and the 1990s trial of the Menendez brothers, who were convicted of killing their parents in a Beverly Hills mansion. There was the trial of the officers accused of beating Rodney G. King and the not-guilty verdicts that set off days of rioting in Los Angeles in 1992.

Judges often discreetly reach out to Edwards to buy a sketch after big trials, and attorneys are known to hang sketches of themselves in their offices.

Edwards, always dressed in a black pantsuit adorned with a Hermes scarf, is a vivacious presence in court. A role on the soap opera “The Bold and the Beautiful” put her in front of the camera. She was cast as a courtroom artist and sketched the attempted-murder trial of actress Hunter Tylo’s character.

About six months later, Tylo was in Los Angeles County Superior Court after she sued Aaron Spelling for pregnancy discrimination.

“I actually drew Hunter Tylo in court after drawing her on TV,” she said. “This could only happen in L.A.”

::

An artist sketched the Salem witch trials of 1692 and documented the 1865 military tribunal of conspirators in the assassination of President Lincoln. The impeachment trials of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, also were captured in a drawing.

With the advent of photography and video, the 1935 trial of Richard Bruno Hauptmann in the murder of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s son became a media hullabaloo — including hidden newsreel cameras, clandestine radio broadcasts and flashbulb bursts.

The aggressive media coverage in the case prompted the American Bar Assn. to lobby the courts to prohibit cameras and radio, which they did for decades. Courts eventually loosened the reins. Federal courts, however, have long banned cameras.

Rule 1.150 of the California Rules of Court, adopted in 1984, gives state judges wide discretion in allowing televised trials.

The O.J. Simpson murder case, the so-called Trial of the Century, was among the first to be broadcast live on television.

“We all thought O.J. was the swan song for courtroom artists,” Edwards said.

The prolonged media circus, however, was sharply criticized after Simpson’s acquittal and is believed to have led to judges becoming more reluctant to allow cameras in the courtroom.

Ronald H. Rose, a retired Los Angeles County Superior Court judge, said the presence of cameras influences the behavior of those involved and can undermine the court’s pursuit of justice. While on the bench, he’d ban the cameras more often than not.

Some attorneys grandstand, others get nervous and make mistakes, he said. Jurors take notice and may try to see newscasts of the trial, which is against the rules. Witnesses can hear the testimony of others on television, perhaps compromising their own memories.

“A courtroom is a place where people strive to really, truly see that justice is done,” Rose said. “I’m always afraid that it isn’t going to be accomplished if we allow cameras.”

Edwards, however, can easily blend in and bring into her drawings the feeling in the entire room.

“She’s the public eye in the courtroom,” Rose said. “She’s able to capture the emotion that is felt by everyone in the courtroom in a way that a camera never could.”

Edwards said she has never been busier. Although that could be attributed to judges moving away from allowing cameras, it could be the lack of artists who can do the job.

The fear of the day when she is no longer needed is always present. Sometimes the phone doesn’t ring for weeks.

“I always wonder, is this the last job? Is this my last story?” she said. “But then the phone rings.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.