The reason for California’s tax volatility: We soak the rich

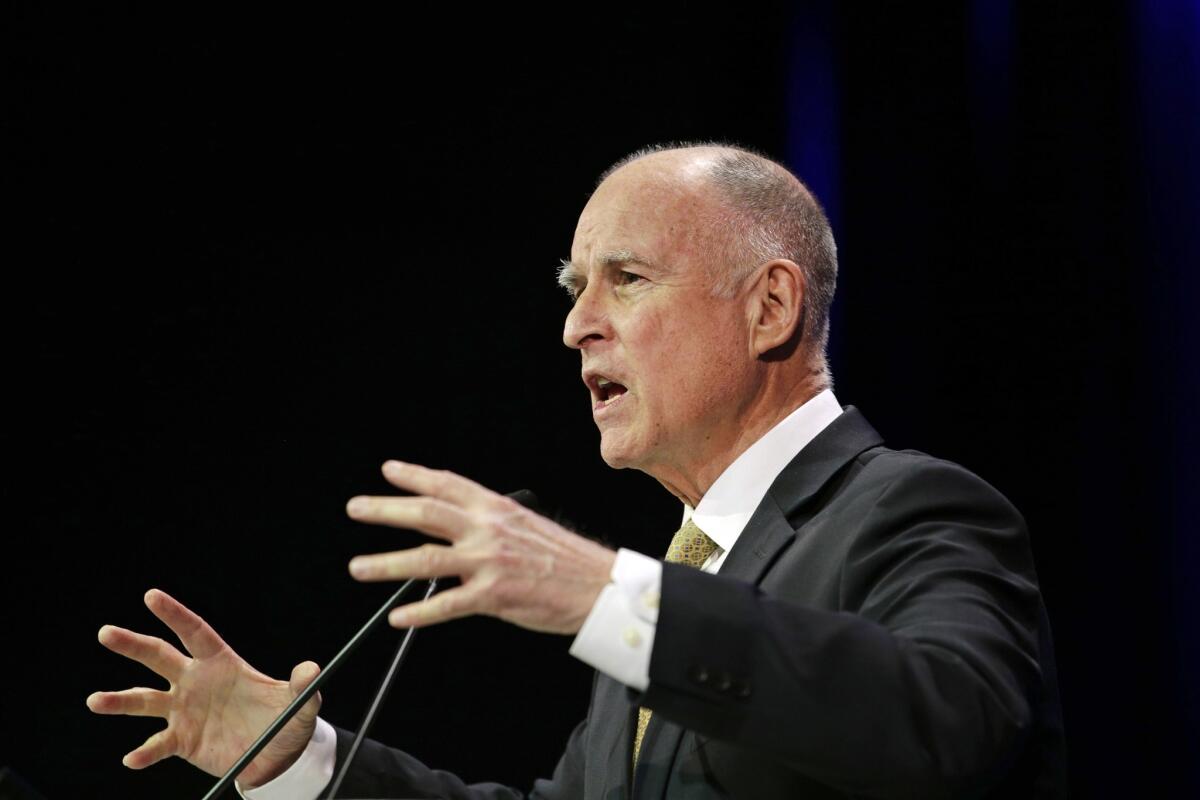

Reporting from Sacramento — The numbers are in, and they’re eye-catching: Gov. Jerry Brown’s “soak the rich” tax increase really did drench them.

And it made California’s harmful tax volatility that the governor regularly rails about even worse.

Tax volatility — the extreme surging and plummeting of income tax revenue — is the scourge that inflicted horrendous budget deficits on the state during the recession.

Brown is trying to treat the symptom of volatility by hoarding revenue spikes in a so-called rainy-day reserve. Then it could be tapped in hard times.

What California should be doing is curing the disease by reforming the tax system, stabilizing it and ridding us of the volatility. Broaden the tax base and bank less on the rich, whose incomes fluctuate wildly during periods of boom and bust.

But that would require heavy lifting — a willingness by Brown to commit political capital and fight powerful interests. He’d also need to explain it to the vast millions of low- and middle-income voters. And neither he nor fellow Democrats in the Legislature have the stomach for that during an election year — or any time.

It’s more popular to draw blood from the rich.

New figures from the Franchise Tax Board show that the wealthiest 1% of Californians paid 50.6% of the state income tax in 2012 — up from 41.1% in 2011. It means that of nearly 15 million tax returns, about 150,000 generated more than half the revenue.

Brown’s Proposition 30 tax hike took effect in 2012. Voters approved it in November, but the huge bumps in income tax rates for the rich were retroactive to January.

Under Prop. 30, the top rate was jacked from 10.3% to 13.3%, by far the highest of any state. The hikes began phasing in for single filers when their earnings exceeded $250,000.

You’d get into the top 5% of income earners at $206,000, according to the tax board. And that group — numbering 748,000 — paid 70% of the state income tax.

To be among the top 1%, you’d have had to earn $525,000 — and the average income in this lofty class was $1.9 million. They earned a quarter of the state’s personal income while paying half the tax.

The dramatic increase in tax payments by one-percenters wasn’t all because of Prop. 30, according to the governor’s state Finance Department. About 60% of it was.

The rest was due to rich people shifting investment income — capital gains — into 2012 to escape federal tax hikes that were about to hit in 2013. Facebook going public also boosted the state tax take. So those factors were one-time-only contributors to tax volatility, the numbers crunchers say.

But it’s indisputable the governor’s tax hike aggravated the state’s dependency on the rich — that was its purpose — and therefore increased the potential for yo-yo revenue collecting.

At last count, the Brown administration expected to collect about $7 billion this fiscal year from Prop. 30 — $5.6 billion by soaking the rich and $1.4 billion from a quarter-cent sales tax hike.

And the word is that the governor will report a multibillion-dollar surplus when he revises his $155-billion budget next week — raising the question of whether a tax increase was even necessary.

For my money, leaning on a relatively few wealthy people for the lion’s share of state income taxes is not a matter of what’s fair or isn’t. It’s about clinging to an unstable tax system rather than creating one that’s more reliable for funding state programs, including education.

Such a tax reform would lower the top income tax rates and ask the bottom 80% of filers — with earnings up to $90,000 — to kick in a little more. In 2012, they paid just 9.4% of the income tax.

And we’d lower the state sales tax rate — also the nation’s highest — while spreading the tax to services, such as car repair labor, legal fees and Clippers tickets. People who fret about the regressive nature of the sales tax should remember that the rich rely more on services than the rest of us. So they’d be the hardest hit.

But easing up on high incomes could make California more attractive to investors and job creators — types, for example, who decide to move Toyota’s headquarters and 3,000 jobs from Torrance to Texas, which doesn’t impose a personal income tax.

Brown isn’t thinking that deeply, however, and neither are most Democratic legislators. They like the populist notion of socking the rich and stashing their money for later use. It polls well.

“It appears to be what the people want when you survey them,” Brown said two years ago when proposing his high-end tax hike. Well, then, that settles it.

Pouring rich people’s taxes into a rainy-day reserve rather than going on a shopping spree for new programs would, however, be an improvement over Sacramento’s behavior in past boom times.

Brown’s plan targets the most volatile earnings: capital gains. He’d stash any capital gains receipts that exceeded 6.5% of general fund revenue. That money could then be used only for debt retirement — such as reducing unfunded liabilities for public pensions — or for future emergencies.

This governor always has a short priority list for legislation, and right now it’s headed by the rainy-day fund. He almost always gets what he wants from the Democratic-dominated Legislature.

In a rare appearance before a legislative committee last week, he cast his proposal in simple terms: “Every dog likes to keep a bone in his backyard.”

Only two Democrats dared mention the words “tax reform.”

But there’ll be no incentive for that until Brown’s income tax hike expires at the end of 2018. And maybe not even then.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.