New redemption law puts squeeze on bottle and can recyclers

Francisco Morataya drives a vanload of empty bottles and cans to Victar Recycling Center in Echo Park every week or so to supplement his wages as an office janitor.

The 61-year-old Eagle Rock resident had been making $200 per load, enough to pay his daughter’s cellphone bill. But that was before a new state law tightened the redemption rules, making it harder for people at the economic fringes to scrape by. Now his take is only $50 to $60, Morataya said.

“It’s really bad,” he said this week, flinging plastic bottles into a garbage bin. “I can’t help my daughter.”

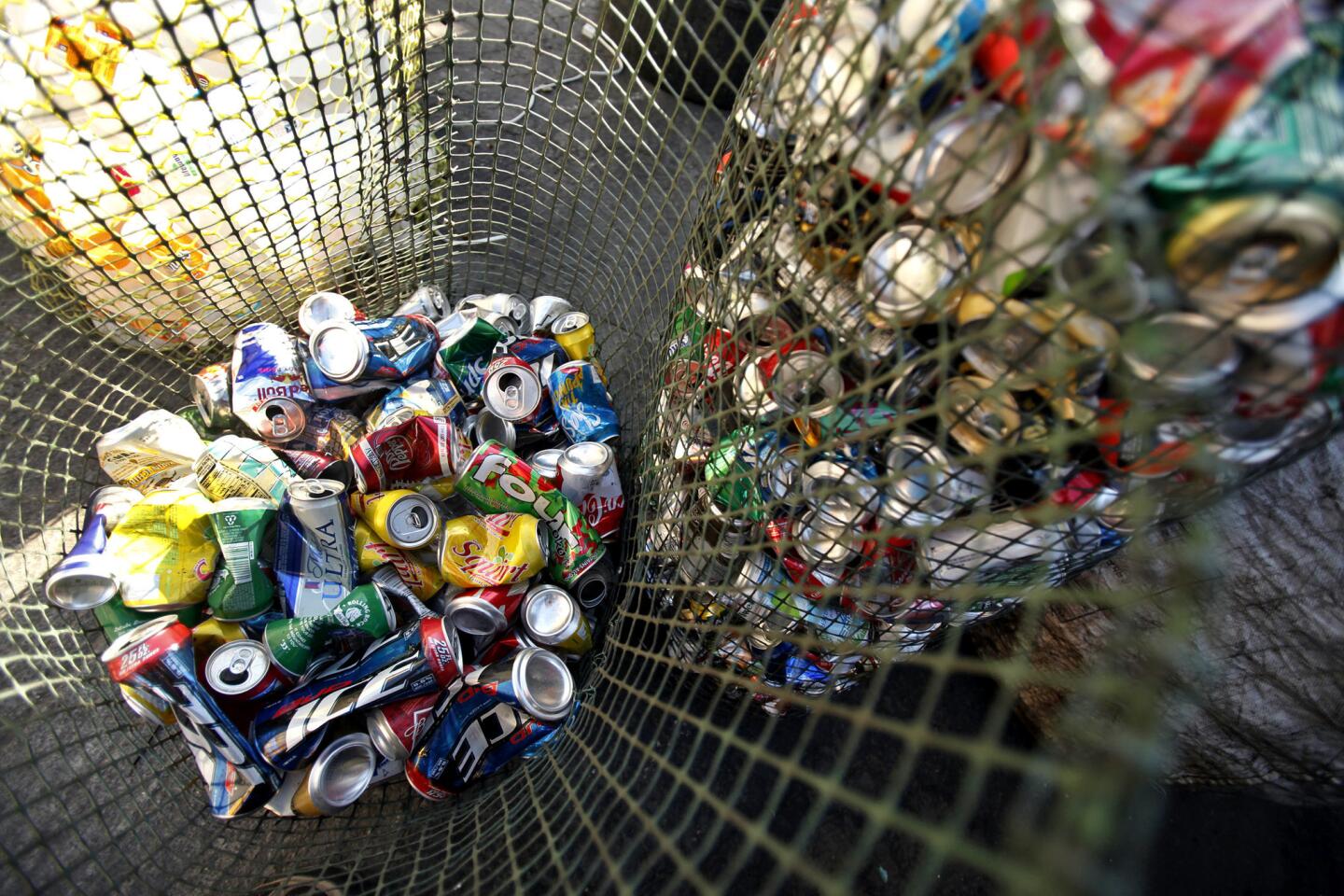

Since 1987, California has charged a nickel or dime deposit on beer and soda cans and other containers that can be redeemed at any of the state’s 2,200 recycling centers. Customers were not charged deposits for wine and liquor bottles, some milk and juice jugs and other vessels, although recyclers could mix them in with redeemable containers and receive some payment.

During the recession, the state’s recycling rates shot up from 65% to 80% or more. That was good for the environment but threatened the solvency of California’s $1.1-billion beverage container recycling fund, said CalRecycle spokesman Mark Oldfield.

Under the new law, recycling centers starting Nov. 1 stopped taking wine, liquor, milk and other containers, except for scrap value, which is negligible.

“The independent recycler, that is where it has a huge impact,” said Chad McKinney, who operates the nonprofit Aware recycling center in San Diego.

A 2010 study by Occidental College environmental economics professor Bevin Ashenmiller found that individual recyclers in the Santa Barbara area earned an average of 7% of their income from returning bottles and cans. For Spanish-speaking people, it was 8.6%.

“It is sad,” said Mayra Tostato, who operates the Chris Recycling center in downtown Los Angeles. “Some people from the older generation are just working to put some food in their mouths.”

For some people, recycling is their sole source of income.

Laid off from his grocery stocking job two years ago, Enrique Lopez Ascension is homeless and had been subsisting on $15 a day he earned recycling at Victar’s. Now, with an income of $6 or $7 on the best of days, Lopez said he is eating out of the garbage.

“I give food to some of the guys when we close,” said Victar’s owner Manuel Labansat. “My wife cooks, and she’s Colombian, so it’s really good.... Many people are in the same situation.”

Oldfield said the state’s $1.1-billion recycling fund had been running a “structural” deficit of $100 million. The state expects to reduce that by $3.5 million to $8.5 million by eliminating recycling payments for “commingled” items that, on their own, would be ineligible for refunds. The new law is part of a wider strategy to close the deficit, Oldfield said.

The state also cracked down on out-of-state recyclers. They were trucking loads of discarded materials into California from Nevada or Arizona, where cans and bottles are not subject to a cash deposit. Officials in 2012 estimated the fraud at $40 million a year. The state imposed load limits and is requiring recycling trucks to submit to inspection when they cross the state border, Oldfield said.

The governor’s budget also proposes eliminating $65 million the state has been paying glass and plastic manufacturers to subsidize a portion of their container recycling costs.

Wine and liquor bottles will continue to be recycled through curbside pickups, Oldfield said. Scavenging from residential and commercial trash cans is illegal in many Southern California communities, though it is widely tolerated.

Susan Collins, of the Container Recycling Institute, a Culver City-based national group, said as much as 40% of glass items are lost to breakage during curbside recycling.

Advocates have repeatedly tried to get the exempted bottles added to the redemption program but have been defeated by the wine industry’s political clout, said Mark Murray, executive director of Californians Against Waste.

“This is one of the rare issues in which Northern California representatives who support recycling are not prepared to vote against the wine industry,” he said.

Gladys Horiuchi, spokeswoman for the Wine Institute, said wine bottles were excluded because they were not part of the state’s litter problem. Her group supports curbside recycling and on-site recycling at wineries, she added.

McKinney, whose San Diego group also trains homeless people in recycling industry jobs, has started a petition to reverse the commingling ban.

The politics of recycling are lost on Richard Stevens, 64, a Vietnam veteran who delivers cans and bottles three times a day to Chris Recycling Center.

“I might go out for four hours or less. It’s hard to say,” the skid row homeless man said last week, leaning on his shopping cart. “What used to pay $20 a load is now $10 or even $8.”

Stevens said he lost his government aid when he relapsed into drug use. His recycling earnings, the only money he’s got, go for food and drink, he said.

“I don’t go to the missions, I don’t wait on lines and I don’t beg,” he said. “I work for mine.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.