Leaving America: With shaky job prospects and Trump promising crackdowns, immigrants return to Mexico with U.S.-born children

Faced with stalling job prospects Maria Barrancas and her partner Ricardo Madrigal — immigrants in the country illegally — decided to go back to Mexico with their two young children. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The girl clutched the goodbye card her friend Emily handed her that morning.

“All thou we’ll be a few miles apart you allways be my best firend.”

Luz Madrigal, 6, sat in the back seat of the car with her little brother Alejandro, heading south to the U.S.-Mexico border and a new home more than a thousand miles away.

Faced with diminishing job prospects and a president who promised to make life harder for them, Luz’s mother and father — immigrants in the country illegally — decided to go back to Mexico.

They joined more than 100 people voluntarily returning since January to Mexico with the help of consulates in Los Angeles, Houston and Chicago.

An hour into the drive, Luz watched the urban blur pass by the car window under a gray sky. She pointed out tall buildings a little ways off in the distance.

“Is that Guatarajara?” she asked.

Her mother did not correct her pronunciation of Guadalajara.

“No,” she said. “We still have a long way to go.”

Five months before, Luz’s parents walked into the Mexican Consulate on the edge of MacArthur Park to make her and her 3-year-old brother — who are American — Mexican citizens as well.

Thousands of others across the country also went to Latin American consulates seeking dual citizenship for their U.S.-born children.

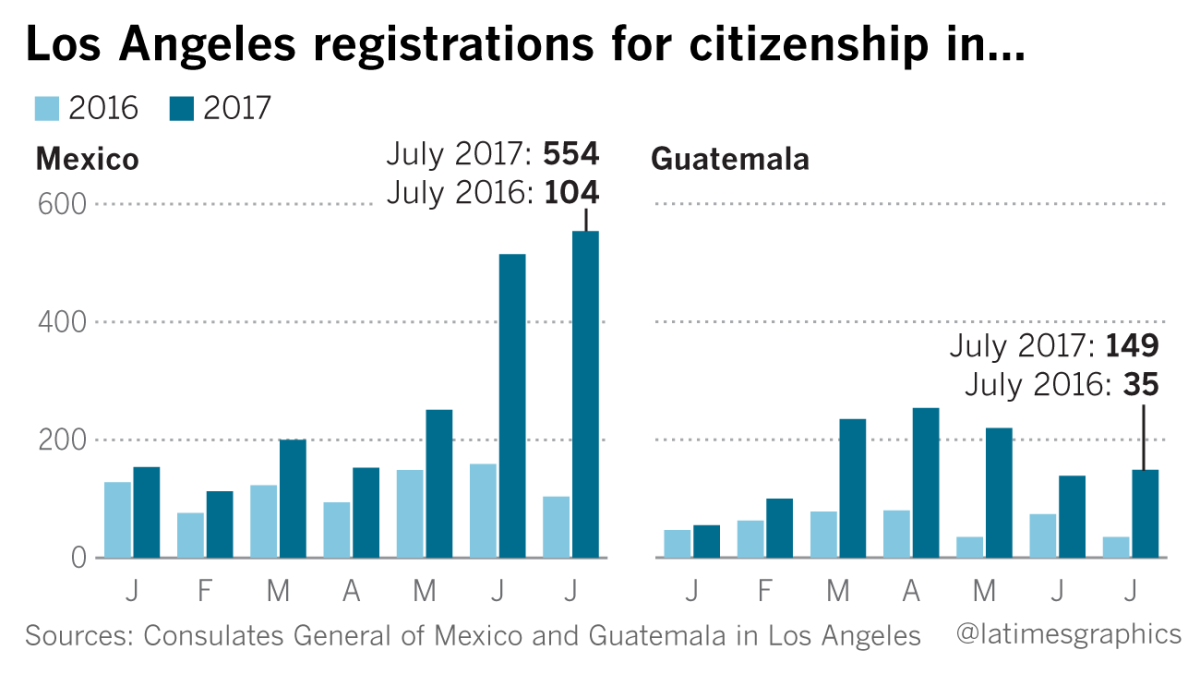

“The increase — the boom — started immediately after the inauguration of President Trump,” said Carlos García de Alba, Mexico’s consul general in L.A. “We can suppose that there are strong reasons to do this. One of those is just to be prepared in case either of you could be deported. It’s better to return to Mexico with children being nationals.”

In the end, Luz’s and Alejandro’s parents, Maria Barrancas and Ricardo Madrigal, decided to get out before it even got to that point.

“They’re sending a message that, ‘You’re not welcome here, we don’t want you here …. We’re going to find you,’” Maria said. “You don’t know if it’s going to be tomorrow, the next month, the next year. You don’t know when they’re going to come knock on your door.”

They told Luz about an idyllic place they planned to move to in Jalisco, about the goats, cows, sheep and beaches in Mexico.

She would meet aunts, uncles and cousins for the first time and ride her grandfather’s horses.

The children would learn later that Mexico was a vast country, and there were tranquil places, and there were places racked by terrible carnage from the drug trade.

For this, Maria and Ricardo were not returning to their home state of Sinaloa, the violent heart of that trade and the land of Joaquin “El Chapo”

Maria and Ricardo settled on the city of Tlaquepaque in Jalisco. Ricardo’s sister lives there and reported that it was safe to walk around, even at night, and that there were private schools that offer bilingual education.

“I worry for them, for their education more than anything,” Ricardo said. “I’m going with the goal that my daughter doesn’t lose her language. The idea is that they’ll come back.”

Eight days before they left, in their two-bedroom apartment in Gardena, Luz copied her multiplication tables into a notebook she would use for homework in Mexico.

For her age, Luz is already a worrier — about her first day of school, about what they will be able to afford and what lies ahead for her family in Mexico.

Sitting among packed boxes in the living room, she practiced with a Spanish children’s book her mother would read to her when she was a year old.

“Dónde estará el osito Peluchín,” Luz read aloud, haltingly pronouncing each unfamiliar word. “Where, oh where is Huggle Buggle Bear.”

“Lo llamo y lo llamo, pero no,” she trailed off, staring down at the word “quiere.” Want.

“Sound it out,” Maria told her. When she was 3, Luz could switch from English to Spanish without hesitation.

“How am I supposed to sound that out?” she responded, casting the book aside for one in English. Luz, who is on a second-grade reading level, finished it within a minute.

There are nearly half a million children who are U.S. citizens enrolled in Mexican schools, the Mexican government said last year. Researchers have found some students struggling to integrate because they cannot read or write in Spanish.

Mexico has not had the long history of immigration like the U.S. and so has not had to grapple with how to accommodate non-Spanish-speaking students in their schools.

“They haven’t thought about creating classes of Spanish as a second language,” said Patricia Gándara, a UCLA professor who heads up education for the UC-Mexico Initiative.

“Without programs to help integrate these kids into the schools and without even the acknowledgment on the part of many teachers that these kids have special needs, they’re not likely to fare really well in the Mexican school system,” Gándara said. “We think it’s a real crisis.”

If large numbers of English-speaking U.S.-born children began heading south, they could swamp the Mexican school system.

There were an estimated 4.5 million U.S.-born children under the age of 18 living with undocumented parents, according to a 2012 Pew Research Center study. A USC analysis found that about 13% of children in Los Angeles County were U.S. citizens with at least one parent without legal status.

An American citizen with a parent who is a Mexican national can become a dual citizen through "registro de nacimiento," or birth registration.

In 2016, from January through August, the Mexican Consulate in L.A. registered 991 births. This year, over the same months, more than 2,000 were registered.

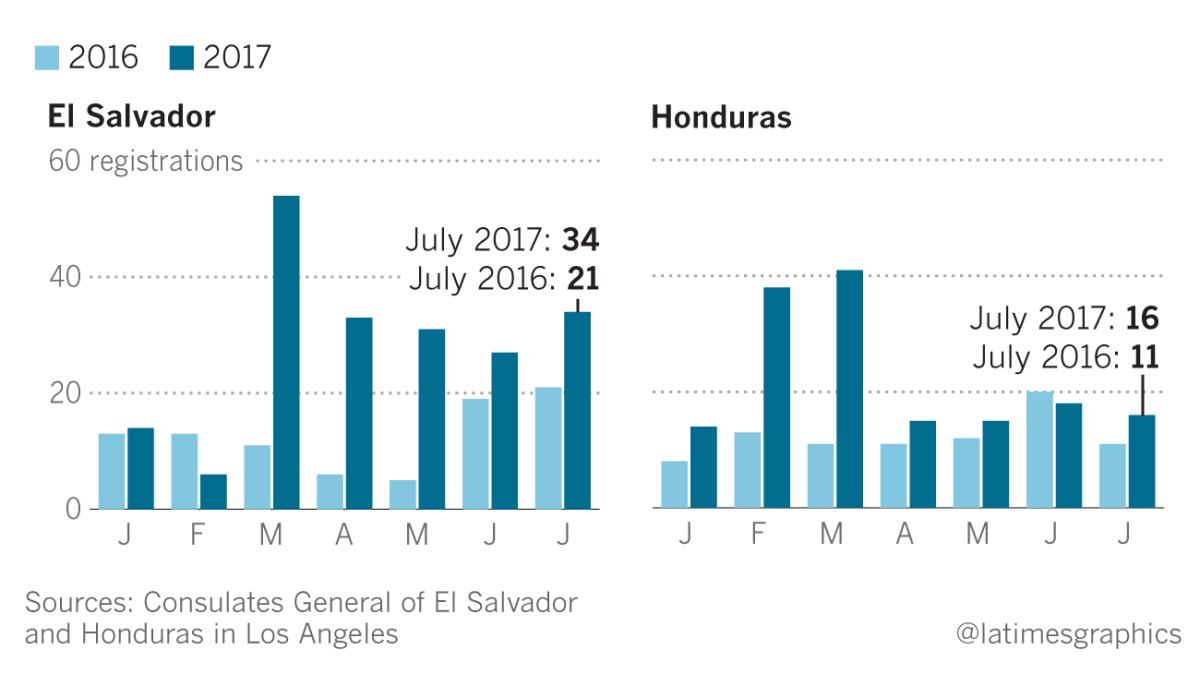

There have also been increases in birth registrations at the consulates of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, credited in part to the new administration.

“I think in part because of the insecurity that’s come with President Trump and the possible changes to immigration,” said Pablo Ordóñez, Honduras’ consul general in L.A. “I think people are preparing for any possibility.”

A dream deferred

Luz’s parents never considered leaving until November. That month, weeks passed with no income on the used cars they had been buying and reselling.

Then there was Trump’s victory — and the message it sent to immigrants like them: They were not wanted.

They suddenly felt under threat.

“We’d rather return voluntarily than be deported,” Maria said.

Through an office of Mexico’s National Institute of Immigration in the L.A. consulate, 47 people since January have been supported in their return to Mexico, as part of a strategy known as “Somos Mexicanos.” Those wishing to return are helped with tax exemptions for belongings and provided a contact in Mexico to help them with job opportunities and integrating into society.

Even before the new administration, Mexican nationals had been leaving the U.S., largely for reasons having to do with family reunification, according to findings released in 2015 by the Washington-based Pew Research Center.

According to census numbers from the U.S. and Mexico, since 2005 Mexican nationals have begun to leave the U.S. in greater numbers than at any point in history. The largest share of those who return to Mexico are immigrants who had been in the country illegally.

The number of people leaving the U.S. began to fall off in 2010. By 2014, fewer Mexican nationals were leaving the U.S. than a decade earlier, but even fewer were coming in from Mexico.

Maria and Ricardo dreamed of one day coming back legally. After speaking with a lawyer, they learned they would have to wait a decade before they could try.

“We have the dream, with God’s grace, that we can return to our home here in the United States,” Maria said. “We know we’re going to our country of birth, but in our hearts, this is our country.”

Luz sat quietly on her bed, her face downcast as she waited for her best friend Emily, who started school at Gardena Elementary. Luz would have been attending the same school if she stayed.

“On the first day of school, I’m not going to have any friends,” Luz said.

This thought haunts her constantly. Maybe, she tells herself, her classmates in Mexico will be impressed with her Barbie collection.

But the fears kept mounting. Her older sister told her the family would have to pay for lunches at school in Mexico. How could her parents afford that? She spent the night before moving day in tears.

“Don’t cry,” Ricardo consoled her. “That’s why you have your mom and dad.”

Ricardo and Maria are thinking about one day opening a mechanic shop, using the skills Ricardo learned while working on used cars. They are not sure yet how they’ll secure an income and are relying on their savings.

Instead, they are focused on the children, renting a townhouse with three rooms — so that when Luz gets there it’ll be “something more beautiful than what we had here,” her mother said. A small house, it’ll cost them under $200 each month.

On the day of the big move, the family packed up the notebook paper where earlier that month Luz had written her birthday wish list: water park, puppy, come back to Gardena.

As Luz buckled in, eyes red and glistening, her father reminded her about the animals waiting in Mexico. It was the best picture he could paint for a 6-year-old. She knew the words by now: vacas, chivos, borregos.

She tucked her face toward Alejandro’s car seat and dozed off for about an hour, still clutching her goodbye card from Emily.

She woke up passing Costa Mesa. Her younger brother occasionally spoke up with the few Spanish words he knew, mostly parroting his parents.

Luz was quiet, watching the last bit of America slip past her window. The brown hills of Camp Pendleton, Legoland. She had been wanting to go to Legoland.

They passed a sign: Mexico Only / No USA Return.

“Please prepare yourself for your new life,” Maria said.

She pointed out the enormous Mexican flag luffing gently in front of them.

Luz got out of the car in Tijuana. She clung to her father’s legs. Tears blotched her T-shirt.

“Quiero regresar,” she said.

“I want to go back.”

ALSO

'My daughters are going to be OK.' Then Trump phased out DACA

California lawmakers approve landmark 'sanctuary state' bill to expand protections for immigrants

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.