Activist battles L.A. County jailers’ ‘culture of violence’

Patrisse Cullors saw what her father and brother experienced and was moved to form the Coalition to End Sheriff Violence in L.A. Jails.

Outside the bunker-like county jail complex, bail bondsmen hover by the visitors' entrance, thrusting fliers at potential customers as they file in to see husbands, sons and friends. Along the sidewalk, taxi drivers hustle for fares among newly released inmates who pace about, dialing cellphones, reconnecting and searching for rides.

A young woman with a short shock of dreadlocks atop a mostly shaved head set off by chunky gold earrings joins them. She has a brisk walk, a broad smile — and a clipboard.

Patrisse Cullors, self-described "freedom fighter, fashionista, wife of Harriet Tubman," comes to the jail complex regularly in search of recruits to her 18-month-old campaign to upend what she contends is a culture of violence among deputies inside the walls.

On this afternoon outside Twin Towers jail, six young activists are awaiting their marching orders from Cullors. Before greeting them, she zeros in on a young Latino sitting on a wall re-threading his shoelaces — inmates have to surrender them for safety reasons when they are booked.

The young man is clean cut and wearing skate shoes. He signs up for Cullors' mailing list, takes a flier for an upcoming sheriff's candidates forum her group is cosponsoring and tells her he served a month for violating his probation on a drug charge — his first stay in the county jail system.

Cullors listens, jotting down information about the man and another inmate he says may have been wrongfully arrested. She promises to put him in touch with a civil rights attorney.

"I know sometimes trouble attracts people," she tells him. "But try to stay out of it. And try to get involved, because you seem awesome."

Cullors and a small group of fellow activists have helped gain new respect and momentum in the halls of power for a once-floundering idea: creating a civilian commission to oversee the troubled L.A. County Sheriff's Department.

From left, activists Tiffany Usher, 22, Jose Garcia, 22, and Bryan Juarez, far right, 19, get Jason Delaney, second from right, to sign a petition to end sheriff violence shortly after Delaney was released from the Men's Central Jail in Los Angeles in late January. Delaney's sister Chadney, center, picked up her brother when he was released.

For more than a year, Cullors' Coalition to End Sheriff Violence in L.A. Jails has applied steady pressure on the county Board of Supervisors, in part by trying to organize a large and unlikely bloc of county voters — former jail inmates. The coalition hopes it can become a constituency with clout in the June election to replace former Sheriff Lee Baca, who unexpectedly stepped down in January.

His department had been under scrutiny by media and advocates for years over alleged abuses in the county jails. A federal investigation led to criminal charges against 18 current and former sheriff's deputies late last year.

County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who has pushed for civilian oversight of the department, lent support to Cullors' effort from the start. But others are skeptical of setting up a commission with no legal power over the elected sheriff.

"They have a legitimate point of view, a point of view that I actually agree with," Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky said. "Where we have a parting of ways is, doing what they want to do is not going to accomplish what they want to accomplish."

Still, Cullors' group made sure the issue stayed on the supervisors' radar — in part by recruiting dozens of former inmates to call Yaroslavsky's office.

My son isn't the same...He'll never be the same. ”— Cherisse Foley

Miriam Krinsky, executive director of the board-appointed blue ribbon commission that studied jail violence in 2012, appreciates the group's efforts:

"The constant drumbeat that they were able to sound underscored for everyone on the commission the importance of the work we were doing."

When Cullors was a child, her father was in and out of jail and prison on drug charges. She would write him letters when he was behind bars. He died in a homeless shelter not long after his last release from prison in 2009.

"It's been a very disturbing part of my life," the 30-year-old said. "I could have done a lot with that experience. I could have just been angry and sort of bitter, or I could do what I'm doing now."

But her quest to reform the jail system stems mostly from her older brother's experience. Just after his 20th birthday in 1999, Monte Cullors was arrested on charges of evading an officer. Patrisse, then 16, said he had been joy-riding in their mother's car and fled from police.

While in jail awaiting trial, Monte had a confrontation with a deputy. In a complaint he sent to a law firm later, he acknowledged he punched the deputy, but said he then put his hands up in surrender. He said a group of deputies beat and choked him until he blacked out and woke up in a pool of his own blood.

According to the deputies' account transcribed in court records, Monte had attacked a deputy who was trying to transport him after a psychiatric evaluation and lunged at another deputy who came to the first one's aid.

Monte was diagnosed with schizoaffective and bipolar disorders during his stint in jail.

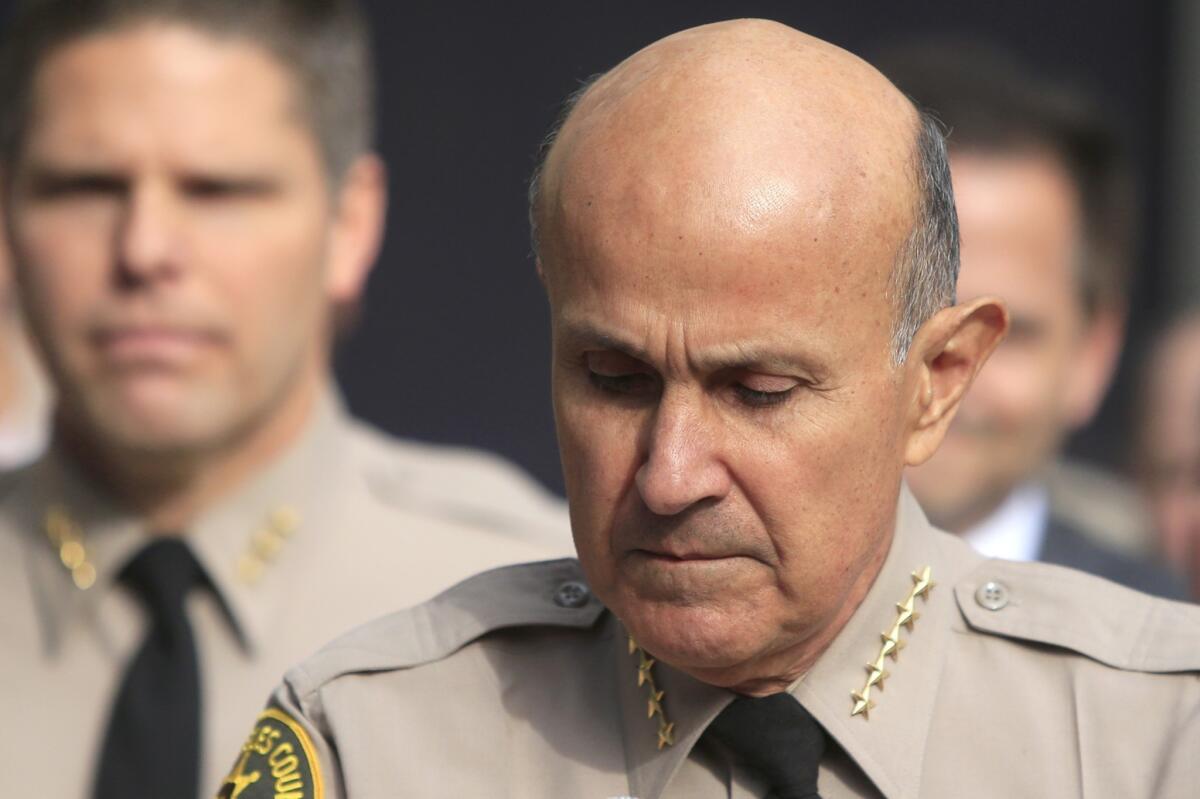

With his command staff standing behind him, then-Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca in January unexpectedly announced he would not seek a fifth term and would instead retire at the end of the month. Patrisse Cullors' Coalition to End Sheriff Violence in L.A. Jails hopes to become a constituency with clout in the June election to replace Baca. (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

"My son isn't the same," said Cullors' mother, Cherisse Foley. "He'll never be the same, and every single day we all worry about him."

Monte was convicted of battery on an officer as well as the original charge of evading police and sentenced to 40 months in state prison. He later approached a law firm in hopes of suing the Sheriff's Department, but the firm rejected the case. Monte has continued to struggle with mental illness and has since served another prison term — Patrisse helped raise $10,000 for an attorney who negotiated a plea bargain and shortened sentence.

She channeled her pain into activism. At 18, she began volunteering with the Bus Riders Union, a public transportation advocacy group organized by the Labor and Community Strategies Center, a Los Angeles think tank. A few years later, she went to work for the center and launched a program to train high school students in political organizing.

"I think she doesn't see her work as different from her life," said Mark-Anthony Johnson, an organizer with the coalition and friend of Patrice Cullors' since high school. "Her life is her work."

Cullors was finishing up a degree in religion and philosophy at UCLA in January 2012 when an alert from the American Civil Liberties Union landed in her inbox.

The group had filed a civil rights lawsuit alleging widespread abuses by the Sheriff's Department. Cullors stayed up all night reading the 86-page complaint, which alleged that gangs of deputies systematically beat inmates and instigated inmate-on-inmate violence.

"I felt like there was finally a voice that was being given to the folks who are voiceless," she said, "not just the people who are incarcerated here, but the family members."

She created a piece of performance art, recording herself reading documents her mother had kept about her brother's case — notes of phone conversations and messages left with jail staff — and playing it as performers depicting inmates pasted an enlarged copy of the ACLU complaint to a wall. Soon after, she and five friends began organizing outside the jails.

Coalition member Sandra Neal, whose son was a plaintiff in the ACLU lawsuit, recalled getting a call from Cullors soon after the group formed. Cullors told Neal about the work she was trying to do and shared her brother's story.

Bryan Juarez, 19, left, and Jose Garcia, 22, right, get Johnny Atencio, 21, to call county Supervisor Zev Yaroslovsky's office to request that he support the campaign of the group Coalition to End Sheriff Violence in L.A. Jails, shortly after Atencio was released from Men's Central Jail.

"I remember vividly becoming very emotional, because that's exactly what I felt there was a need for," Neal said. "I think we were both crying on the phone, because we really connected, and I said, 'I'm in.'"

Since then, the group's active membership has grown to about 50, and Cullors has made it her full-time job. Until recently, the work was funded by people giving money at events and on websites such as GoFundMe.com — about $40,000 in the first year, Cullors said. The organization she set up to run the coalition, Dignity and Power Now, now is sponsored by the nonprofit Community Partners.

The coalition organized dozens of people to attend and speak at meetings of the Board of Supervisors and the jail violence blue ribbon commission. They held news conferences and marches and lined up at regular county board sessions to call for civilian oversight. They met with Baca himself to present their demands.

The former sheriff, via a spokesman, said that "advocacy groups such as the coalition are important in any reform effort." He declined to comment further on the group's work. A day before announcing his retirement, Baca voiced support for creating an oversight commission.

The Board of Supervisors has since ordered a study of how such a commission could be structured.

As the sun began to set over downtown Los Angeles, Cullors rounded up her team to head home. Two just-released inmates were chatting up a young female coalition activist.

"You made friends!" Cullors said as she collected her intern and walked on. "Make sure they show up for the debate."

"We're coming!" one of the men shouted after them.

Cullors has a lot to do: There are more candidate debates to organize, more county officials to call, more meetings to go to. But she's most excited by the afternoons at the jails, she said:

"You have some of the most disenfranchised people in our county coming out, hearing people say, 'You can do something.'"

FOR THE RECORD:

Jail activist: An article in the April 14 Section A about jail activist Patrisse Cullors included a reference that misspelled her first name as Patrice.

Follow Abby Sewell(@sewella) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Arts blossom in a 'garage salon' in Bell

We don't have plays, we don't have museums, we don't have anything.”

A couple's commitment to skid row doesn't waver

The goal is to be a witness to suffering and injustice, and try to help.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.