Must Reads: One cop came forward to expose secrets in his own ranks. The revelation rocked the court system

Pittsburg Police Officer Michael Sibbitt was ready to testify in a murder trial when a lieutenant from his own department rushed to the courthouse to reveal a startling secret.

The lieutenant told the court that the officer had resigned more than a year earlier during an investigation into whether he had falsified reports and used excessive force.

Details about allegations against Sibbitt and his partner had not been disclosed in more than a dozen other criminal cases in which the officers had made arrests.

The revelation in a Contra Costa County courthouse in 2015 had a sweeping effect: Nineteen convictions secured with help from the two officers were dismissed after prosecutors learned of the misconduct investigation.

The incident rocked the criminal justice system in this Bay Area suburb and showed how information from officers’ confidential disciplinary files can change the outcome of cases — if courts are made aware of the material.

The case was unusual because the lieutenant took it upon himself to reveal the officer’s background. Most of the time, getting this information into court is a convoluted process that often leaves judges, attorneys and jurors in the dark about misconduct by officers who take the stand in criminal proceedings.

“It’s one of the more stark examples of why we need to have more transparency about police officers’ backgrounds,” Laurie Levenson, a former federal prosecutor who teaches criminal law at Loyola Law School, said about the case.

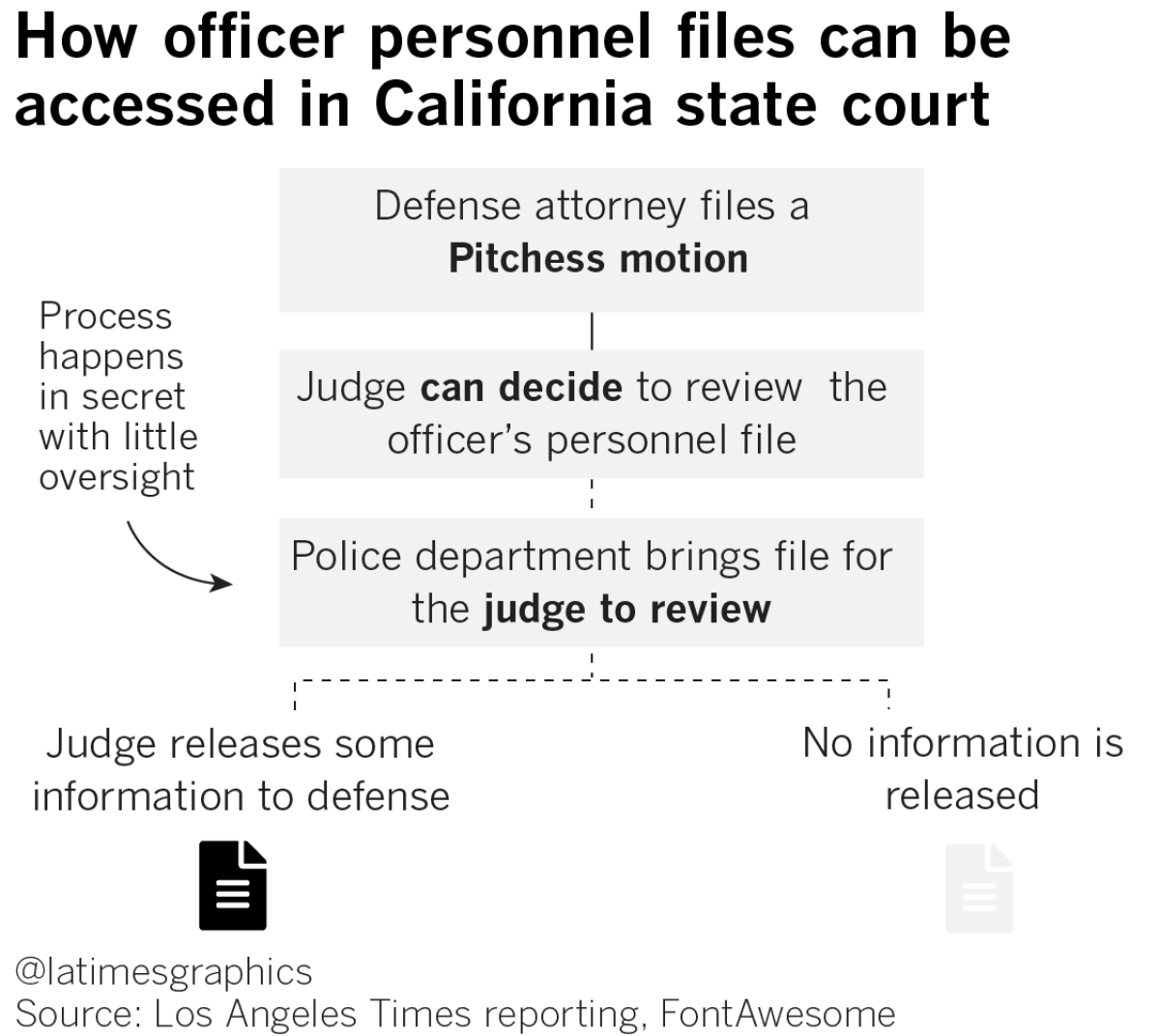

Internal records of police misconduct are confidential in California, but state law allows judges to order police agencies to bring personnel files to court if an officer’s credibility is formally challenged.

Judges, who review the files privately with only a representative from the police agency, rely on departments to present them with complete and accurate documents. Unlike in open court, where lawyers can argue about evidence, prosecutors and defense attorneys are not allowed to review the records with the judge.

This is not how much of the country operates. In 21 states, records of significant police discipline are public. In many others, prosecutors and defendants are able to access them, eliminating the need for a judge’s private review.

A Times investigation

Aug. 9, 2018

An L.A. County deputy faked evidence. Here's how his misconduct was kept secret in court for years.

Aug. 9, 2018

You've been arrested by a dishonest cop. Can you win in a system set up to protect officers?

Aug. 10, 2018

This L.A. sheriff's deputy was a pariah in federal court. But his secrets were safe with the state.

Aug. 15, 2018

Here's how California became the most secretive state on police misconduct

But California is the only state in which even prosecutors cannot directly access the personnel file of a police witness. State lawmakers are weighing a proposal this month that would allow the public to see some law enforcement misconduct records.

The police lieutenant in Pittsburg, Calif., a small industrial city 34 miles northeast of San Francisco, said he decided to inform a judge after learning that his department had not given the court information about Sibbitt and his partner in other cases.

The lieutenant, Wade Derby, knew about the investigation because he’d been the one to conduct it. The officers resigned before his inquiry was finished, but months later, some of the people whom the cops had arrested were still facing trial.

When judges ordered the Pittsburg Police Department to show them evidence of wrongdoing in the officers’ files, the agency did not bring documents from Derby’s investigation, court records show.

Derby raised concerns in memos to his chief that the department wasn’t revealing the evidence and could be violating the law. He said he was prepared to tell the court himself.

“My whole career I have tried to stand up against wrong, and sometimes it was going on in my own place” of work, he said.

Pittsburg Police Chief Brian Addington acknowledged that his agency failed to properly disclose the documents, but he said the omission was unintentional. He declined to answer additional questions.

Document

"If we do not disclose this information we will likely compromise or have a criminal conviction on a domestic violence homicide case overturned. In addition there will likely be civil ramifications from the victim's family. Finally, I believe we will bear possible criminal culpability for violating State and/or Federal laws for nondisclosure."

— Memo by former Pittsburg Police Lt. Wade Derby

see the documentSibbitt and his partner, Elisabeth Terwilliger, filed a lawsuit denying they used excessive force and accusing a department supervisor of ordering them to write reports that left out details about hitting suspects with flashlights. They said the department forced them out after Sibbitt complained that the agency required officers to falsely downgrade reports of serious crimes to misrepresent its crime statistics.

In court papers, the department denied the officers’ claims, but it later agreed to pay them $47,500 each. The city said it would note in their personnel files that the internal affairs investigation was never completed and that “no negative findings were ever made,” according to a copy of the settlement agreement. The officers agreed they would never work for the city again.

The agreement, which includes a confidentiality clause, was not disclosed by the city until Wednesday, a day after this article was originally published online.

Sibbitt declined to speak about the case; Terwilliger did not respond to requests for comment.

‘My flashlight is getting to play’

Sibbitt had been a cop for five years when he began mentoring Terwilliger, a rookie officer.

Derby, the internal affairs lieutenant, found troubling messages on the officers’ patrol car computers.

Sibbitt sometimes wrote advice to Terwilliger, teaching her how to instigate high-speed chases and find people to arrest, according to internal department chat messages obtained by The Times.

“Just drive with your lights on back and forth on Leland until you get a vehicle that doesn’t yield and takes off on you. Totally illegal but it works,” he wrote to her in late 2013 from his patrol car computer.

A few months later, he warned the officer not to attribute that type of advice to him. Terwilliger replied: “I’ll just call it fishing. Officer Sibbitt taught me to fish.”

Document

"JUST DRIVE WITH YOUR LIGHTS ON BACK AND FORTH ON LELAND UNTIL YOU GET A VEHICLE THAT DOESNT YIELD AND TAKES OFF ON YOU. TOTALLY ILLEGAL BUT IT WORKS"

— Message sent on patrol car computer by former Pittsburg Police Officer Michael Sibbitt

see the documentOn April 26, 2014, Terwilliger said she wanted to watch a police dog “gnaw on someone.” But the dog was not available, Sibbitt replied.

“Maybe a flashlight party is in order?” she wrote. “U have to teach me that good flashlight work.”

The next night, Sibbitt struck a boy with his flashlight as Terwilliger struggled with the suspect, according to court records. The juvenile, who officers thought was armed, had an unloaded BB gun.

Some departments warn officers against hitting people with flashlights because they can inflict more severe injuries than batons.

“Two weekends in a row my flashlight is getting to play,” Sibbitt wrote his partner about an hour after the incident.

“Good flashlight work kid,” replied Terwilliger, whose last name was Ingram at the time.

The officers failed to document that they hit people with flashlights on two occasions, according to a Pittsburg police memo filed in court. The department launched internal-affairs and criminal inquiries into whether they used excessive force and lied on reports.

Their badges and guns were seized on June 18, 2014. They resigned six weeks later.

None of this was told to judges or the people who were still facing trial after being arrested by Sibbitt and Terwilliger.

In one case, Terwilliger took the witness stand against a man she had arrested on suspicion of possessing drugs and a firearm but never mentioned that she had been placed on leave two days earlier.

Terwilliger testified that Carl Schoppe was combative and made evasive movements near his car when she approached him. She found a glass pipe in his pocket and discovered a pistol and baggies of powder that turned out to be methamphetamine in the vehicle.

Schoppe accused the officer of lying, saying that he had never made any furtive movements and that he had cooperated with Terwilliger from the start. His girlfriend, who was in the car at the time, said the weapon was hers, not Schoppe’s.

Schoppe filed a so-called Pitchess motion asking a judge to review any potential evidence of misconduct in Terwilliger’s file.

After granting the motion, the judge ordered a police representative to bring the officer’s internal affairs file to a judge for a private viewing.

Under the law, if a judge determines that some of an officer’s file is relevant to the case the court may release some information, but the documents are not entered into the public record.

Police advocates say the process is necessary to balance an officer’s right to privacy against a defendant’s right to a fair trial. Robert Rabe, an attorney who represents several police associations in California, said that the 1978 law that created the Pitchess system has “stood the test of time” and that problems are rare.

“The great majority of the men and women in law enforcement … comply with Pitchess requests and provide what’s necessary,” he said.

But in Contra Costa County, the Pittsburg Police Department failed to deliver the documents about Sibbitt and Terwilliger after judges had ordered the files be brought to court. Judges had no way of knowing there were, in fact, relevant records that should have been handed over.

Schoppe’s Pitchess motion yielded no records on Terwilliger. He pleaded no contest to being a felon in possession of a firearm and was sentenced to 16 months in prison.

Two other defendants who filed Pitchess motions also entered pleas after judges said there was nothing to disclose about Sibbitt or Terwilliger.

They were among the 19 defendants whose convictions depended on the word of the two officers.

Priscilla Cardenas was eating at a Salvadoran restaurant in Pittsburg in 2013 when a waitress called the police on her. The waitress, who’d been a victim of an armed robbery at a food stand months earlier, said she recognized Cardenas as one of her attackers.

Sibbitt responded to the call and showed up at the restaurant. He spoke to the waitress, wrote down Cardenas’ contact information and issued a police report of the encounter.

Cardenas, then a 21-year-old community college student with a clean record, was later arrested and accused of using a handgun and a knife in the taco truck robbery — an offense that carried a maximum seven-year sentence.

Cardenas claimed she was innocent and had been four hours away in Bakersfield at the time of the robbery. The waitress said the robber spoke fluent Spanish with a Salvadoran accent. Cardenas, a California native, said she does not speak Spanish well.

Cardenas’ attorney said no one notified her of any reason to distrust Sibbitt, so she didn’t file a Pitchess motion seeking background on the officer.

Sibbitt testified at Cardenas’ trial, six months after he had resigned from the Police Department and four months after he had taken a job as a Macy’s loss-prevention officer. He told the jury the waitress was “shaking” and “stuttering” upon seeing Cardenas at the restaurant. That testimony helped convict Cardenas in February 2015.

She was sentenced to three years in prison.

It would take several more months before Derby revealed the extent of Sibbitt’s file to a judge in the murder trial in October 2015.

After Derby filed a civil claim alleging retaliation by the Police Department in March 2016, the two officers’ alleged misdeeds were made public. His allegations, first reported by the East Bay Times, prompted the county’s public defender’s office and local prosecutors to launch a review of the officers’ cases.

In his civil case, Derby described his investigation against Sibbitt and Terwilliger, claiming he was pushed out of the department by his managers after exposing the information. The department denied wrongdoing, noting that Derby had agreed to resign after he was found to have sexually harassed another officer. A judge recently dismissed Derby’s civil suit and he is appealing.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Brady vs. Maryland and later rulings require prosecutors and police to alert defendants to favorable evidence, including information that could undermine the credibility of government witnesses. Once the details about Derby’s investigation became public, several defendants argued that they’d been unlawfully deprived of the information about the officers’ alleged wrongdoing and never had the chance to attack their credibility.

Contra Costa County prosecutors looked into other criminal cases where the two officers had testified to determine whether the defendants should have been notified about the information. That also included a look at cases in which defendants accepted plea deals without going to trial.

“If I have reason to doubt the credibility of an officer, or a witness, then anything that witness introduces, I can’t use,” said Lynn Uilkema, a Contra Costa County prosecutor who was involved in the dismissals.

Those concerns pose an especially high risk to prosecutions of low-level crimes, such as drug possession and resisting arrest, which often rely heavily on an officer’s eyewitness account. An internal affairs finding that an officer has lied in the past could undermine the prosecution of a minor crime in which there is little evidence other than an officer’s word.

Of the 19 convictions thrown out by Contra Costa County prosecutors, seven involved nonviolent felonies, such as drug possession or being a felon carrying a firearm. Eleven others were misdemeanors or infractions — DUI, petty theft, domestic abuse, false representation to a police officer, disturbing the peace or resisting arrest. Most of the defendants pleaded no contest.

In at least some cases, there was compelling evidence that defendants were in fact guilty. One man convicted of carrying a loaded, concealed firearm told The Times the weapon had indeed been in his car.

In the murder trial in which Derby revealed the extent of the records on Sibbitt, prosecutors dropped him as a witness rather than risk his credibility being questioned in front of jurors.

Even in Cardenas’ case, which involved other evidence on top of Sibbitt’s testimony, prosecutors found they could no longer stand by her conviction, given the allegations about the police officer’s past misconduct.

They offered to throw out Cardenas’ armed robbery charge and release her immediately if she would plead no contest to a lesser count of grand theft. She agreed.

Since her release, she said, she’s had difficulty finding permanent jobs and stable places to live.

Before she was arrested, Cardenas was taking courses at a local college near Pittsburg and was interested in studying criminal justice.

“I was going to be a police officer,” she said.

Times staff writer Ben Poston contributed to this report.

Twitter: @mayalau

UPDATES:

4:50 p.m., Aug. 15: This article was updated with additional details about a settlement between the city and Sibbitt and Terwilliger.

This article was originally published Aug. 14 at 3 a.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.