Does the LAPD treat celebrity burglaries differently from the average home break-in?

- Share via

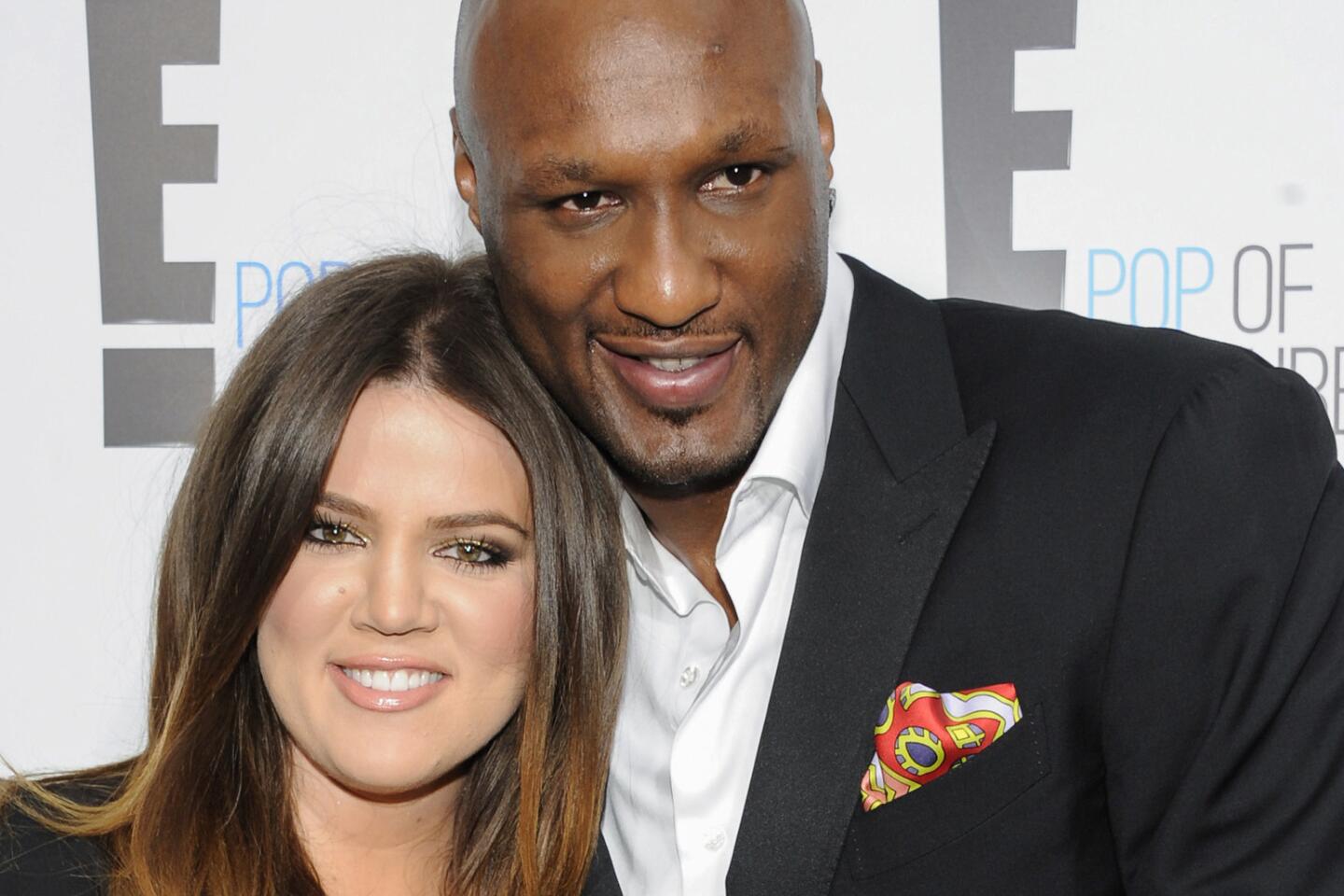

Thieves who crept into Alanis Morissette’s Brentwood home in February made off with a stash worth $2 million, including the singer’s treasured vintage jewelry.

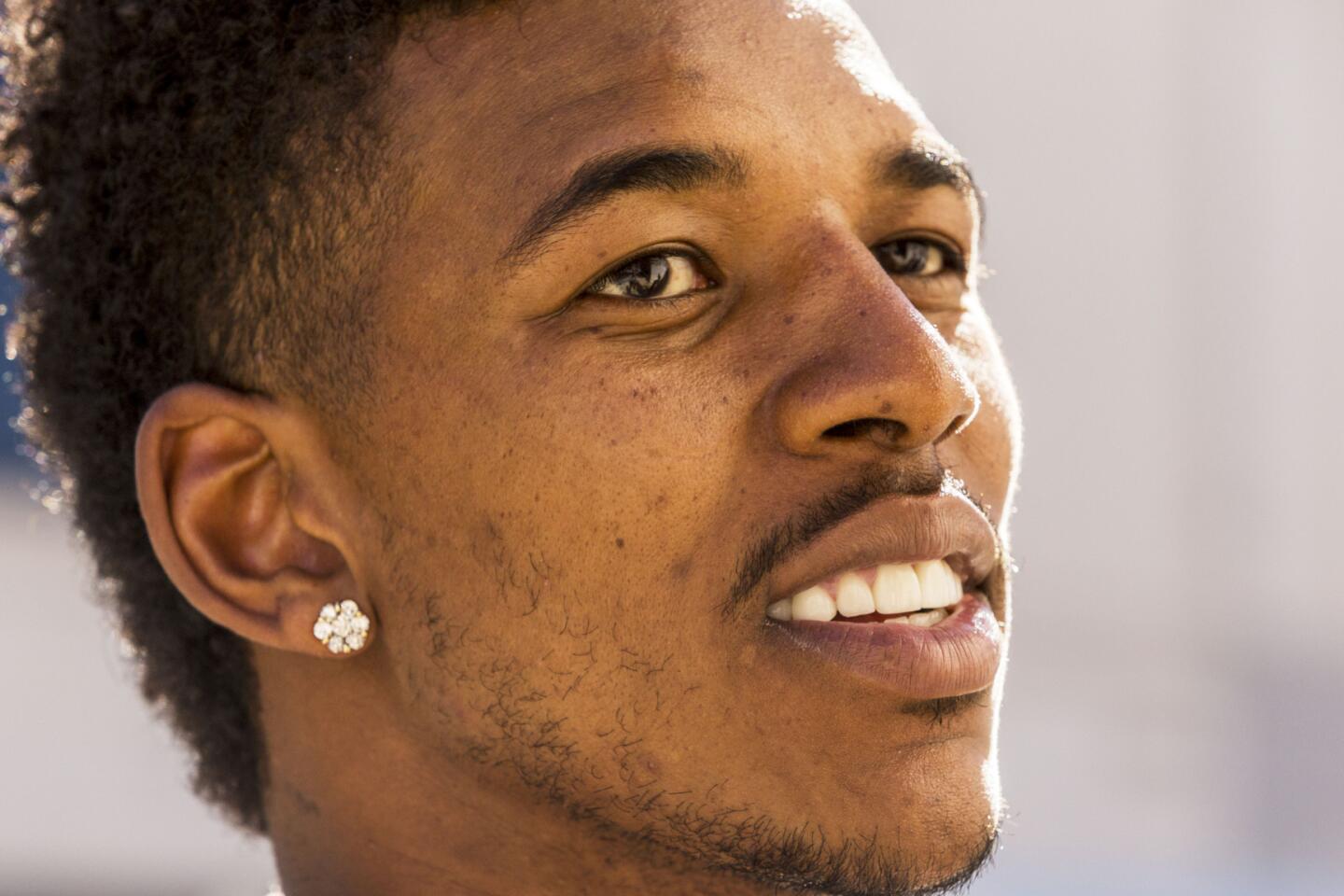

A week later, someone broke the window of former Lakers guard Nick Young’s house in Tarzana and stole a safe stocked with $500,000 in valuables.

At both crime scenes, LAPD investigators meticulously dusted for fingerprints.

They did the same after a burglar stole valuable watches and jewelry from Dodger Yasiel Puig and after former Laker Derek Fisher reported a loss of $300,000 at his home in Tarzana.

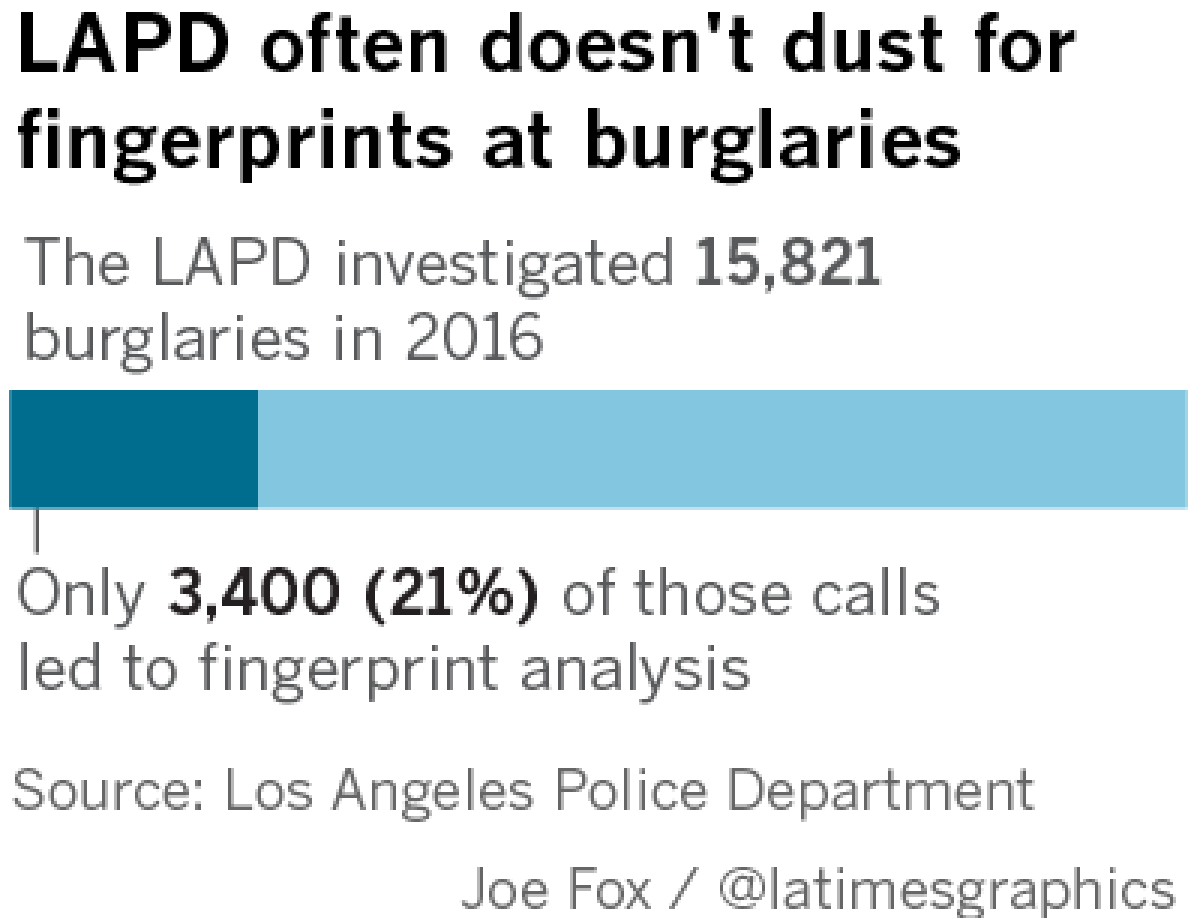

Not everyone who has their home burglarized gets the same treatment. Because of a shortage of crime lab analysts, only about 21% of burglary calls result in fingerprints being collected, according to LAPD figures.

The LAPD said the lack of resources means detectives must make difficult decisions to prioritize cases. As a result, the vast majority of the city’s residential burglaries face strict limits on the number of fingerprints they can send to the department’s crime lab.

LAPD officials said they give priority to break-ins they believe are part of a crime series or committed by professional burglary crews. They also prioritize big-ticket cases where unique items, such as art work or jewelry, are stolen or where security cameras capture prowling suspects and offer a good chance at making an arrest.

“It’s not the [victim’s] name that matters,” said LAPD Assistant Chief Michel Moore. “However, the value of items taken certainly is an influencer and would prioritize them.”

For the LAPD and other police agencies, whether it is worth looking for fingerprints at a crime scene depends on a variety of factors. Rain, for example, could make it all but impossible to find prints on outside windows. Or the break-in could have been reported after a victim’s home was cleaned.

A dozen break-ins of celebrity homes since October have been assigned to the LAPD’s elite Commercial Crimes Division, a specialized team of investigators who almost always lift fingerprints. They say investigators initially suspected that some of the break-ins could be the work of a single crew of thieves. Commercial Crimes detectives, they said, are specially trained in tracking down such professionals and handling serial crimes that cross division or city boundaries.

“It is not because the person is a celebrity,” Capt. Charles Hearn, who oversees the division, said of taking fingerprints at the properties of famous victims.

Hearn’s detectives have expertise in art theft and safe cracking. His unit is based downtown at the LAPD’s headquarters, and he spoke about the investigations during an interview at his office, where the words “Celeb Burglaries” were written in dry erase marker on a small white board. Hearn said he knows of at least two burglaries of celebrity homes that are being handled by other divisions.

So far, he said, investigators have not found any evidence to link the celebrity cases to a common suspect, and the fingerprints have not helped identify possible thieves.

Peter Bibring, a senior attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said he was troubled that detectives would use the value of stolen items in deciding what resources to allocate to a burglary. Doing so, he said, raises concerns that wealthier residents will get better treatment from police.

“Obviously, $5,000 or $10,000 stolen from any working class family has a lot bigger impact on them than a far higher number for a movie star,” Bibring said. “Assigning resources on the value of the theft doesn't sound like a great idea.”

The limits on analyzing prints can also impede investigations. Police and law enforcement experts said departments that take more fingerprints are likely to solve more cases.

From 2010 to 2016, the LAPD logged more than 110,000 burglaries and cleared 11.5% of them, according to a Times analysis of the most recent data collected by the California Department of Justice. The statewide clearance rate for burglaries was 12.4%.

A case is considered cleared when police arrest or charge a suspect, according to FBI guidelines. In some cases, police can count a crime as cleared if the suspect dies or cannot be extradited, or if a victim refuses to cooperate.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department was near the top in the state among large jurisdictions, clearing 15.4% of burglaries in the same period, records show.

Exactly why is unclear because the Sheriff’s Department does not keep a tally of how often fingerprints are lifted. However, records from property and other offenses show the agency analyzes fingerprints in about 55% of cases where investigators visit a crime scene, compared with 35% at the LAPD.

“The more prints you take, the more success you have,” said Dean Gialamas, director of the Sheriff’s Technical Services Division, noting that most of the fingerprints taken by sheriff’s investigators were from burglary scenes.

The Sheriff’s Department does not have staffing shortages that would limit how many prints can be collected or analyzed from property crime scenes, said sheriff’s Cmdr. Bill Song with the Technical Services Division.

At the LAPD, budget and recruitment woes over the years have thinned the ranks of the department’s civilian fingerprint technicians and supervisors.

Agency figures show that 83 supervisors and staff worked in the forensic unit in 2007. Staffing levels fell in the following years, dropping to 58 in 2014. Since then, the unit has climbed to 67 employees but remains short-staffed, according to the department.

The continuing shortage means that each of the department’s 21 geographic divisions — from Devonshire in the San Fernando Valley to Harbor in San Pedro — are limited to sending only 10 fingerprint evidence kits to the crime lab every month for property offenses. Those restrictions do not apply to violent crimes, and the LAPD detective bureau can order additional collection for high-priority cases.

The idea of unequal treatment when it comes to burglaries frustrates some victims who feel they were neglected.

In March, Kevin McMahon, 44, discovered that camera equipment, editing systems, laptops, power tools and family heirlooms had been stolen from his downtown Los Angeles storage unit.

He estimated the loss at nearly $30,000, and said some of the items were irreplaceable, such as the guitars and amplifiers used by his late father, Ken, a musician who gained fame in the Midwest as the lead singer and guitarist of the rock band Haywood Wakefield.

McMahon said he requested a fingerprint analyst several times, but that the LAPD turned him down. When he discovered one of his guitars — a 1992 red Peavey Predator — listed on Craigslist, he said he continually prodded a detective to look into it. McMahon said he eventually got the guitar back after he saw it on sale for $250 on Craigslist, but that no one was arrested.

“It feels like they don’t really care, it’s not a big deal to the police that it’s happening,” said McMahon, who has worked as a director, screenwriter and production manager. “I’ve been struggling the last few years. And to lose priceless things to my family? I have no way to recover that stuff. When normal people get things stolen, it hurts us more.”

Asked by The Times why prints weren’t lifted from McMahon’s break-in, LAPD Lt. Lonnie Benson said detectives do not recall the reason but he promised they would now go and fingerprint the storage unit.

Burglary is a difficult crime to solve. Home break-ins typically occur during the day when residents are away and are often reported to police hours or days later, making it hard to locate eyewitnesses.

William Sousa, director of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ Center for Crime and Justice Policy, said television shows such as “CSI” have created unrealistic expectations for how often police are likely to solve property crimes.

He said it could make sense to prioritize high-end burglaries because the chances of locating expensive, unique items in underground sales markets are a lot higher than finding engagement rings or other pricey but common consumer goods nabbed from the average home.

“With artwork or very distinct high-end jewelry, the property may be easier to find,” Sousa said.

But residents in some middle-class neighborhoods complain they don’t get the resources they believe they deserve.

Jaime Gallo was at work in late 2014 when he got a call from his home security company that his alarm had been tripped. He rushed to his Arleta home to find a business card stuck in the front door. An LAPD officer had written a note, saying the incident was a false alarm.

But as Gallo walked around to his backyard, he could see that an intruder had punched out a screen window and left shoe prints on the side of the house, probably tripping the alarm.

He filed a report with LAPD’s Mission division but said the department did not send anyone to take fingerprints at his house. An LAPD spokeswoman confirmed no prints were taken but said she didn’t know why. The detective who handled the case has retired.

“They didn’t follow up,” Galllo said, adding that other neighbors have had similar complaints. “It seems like they don’t take fingerprints very often, especially over here in the eastern San Fernando Valley.”

Follow @bposton @lacrimes @corinaknoll on Twitter.

ALSO

Man who caused fatal freeway crash that killed deputy is convicted of second-degree murder

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.