While homelessness surges in Disneyland’s shadow, Anaheim removes bus benches

- Share via

Sweat rolled down Ron Jackson’s face as he pondered, as he does every day just steps from “the Happiest Place on Earth,” where he would sleep.

The homeless man’s hangout in Anaheim had until recently been a grimy bus bench across the street from Disneyland.

Then, one day, the benches around the amusement park — including his regular spot outside of a 7-Eleven at Harbor Boulevard and Katella Avenue — disappeared.

Soon, people were competing for pavement.

“No more sleeping spot. Just concrete,” Jackson, 47, said on a sweltering day. “There were already people claiming the space.”

The vanishing benches were Anaheim’s response to complaints about the homeless population around Disneyland. Public work crews removed 20 benches from bus shelters after callers alerted City Hall to reports of vagrants drinking, defecating or smoking pot in the neighborhood near the amusement park’s entrance, officials said.

The situation is part of a larger struggle by Orange County to deal with a rising homeless population. A survey last year placed the number of those without shelter at 15,300 people, compared with 12,700 two years earlier.

Desperation amid Orange County’s riches

In a wealthy county known for suburban living and sun-dotted beaches, the signs of the homeless crisis are getting harder to ignore.

At the county’s civic center in Santa Ana, homeless encampments — complete with tents and furniture and flooring made from cardboard boxes — block walkways and unnerve some visitors. Along the Santa Ana River near Angel Stadium, whole communities marked by blue tarp have sprung up. In Laguna Beach, a shelter this summer is testing an outreach program in which volunteers walk the streets offering support and housing assistance to homeless people.

Cities across California — notably Los Angeles and San Francisco — are dealing with swelling ranks of the homeless. But officials in Orange County said most suburban communities simply don’t have the resources and experience to keep up.

Susan Price, Orange County’s director of care coordination, said officials are trying to build a coordinated approach involving all of the more than 30 disparate cities that takes into account the different causes of homelessness, including economic woes, a lack of healthcare and recent reforms in the criminal justice system.

Most cities “don’t have capacity to respond to all the issues of homelessness effectively. That’s why we need a regional strategy,” Price said. “Every city has been grappling with this issue and not all cities are full-service so that means we need to find out what each other is doing and figure out how to combine resources.”

The homeless problem often stands in stark contrast to the perceptions many have about Orange County.

Cleaning up Disney’s home

Anaheim is Orange County’s largest city and home to Disneyland, one of the region’s biggest draws and tax generators. The city has spent more than two decades trying to clean up the area around the park — once noted for run-down motels and prostitution — into a family-friendly, tourist-oriented “resort district.”

“It breaks our heart to have to remove those benches,” said Mike Lyster, a city spokesman. “But their purpose is to provide seating for someone waiting for a bus.”

He stressed that the bench removal was not tied to concerns about Disneyland visitors. “We’re not taking this action because of tourism. We never had a request from Disney,” Lyster said. “But we did hear from small shop owners and motel owners about the safety issues so we stepped up.”

Homeless advocates said Anaheim is just one of multiple cities along Beach Boulevard, one of the county’s busiest thoroughfares, to cut down on bus benches.

“Removing benches is a minor thing, it’s a band-aid approach. People will still congregate because these are areas where they’ve chosen to be,” says Paul Leon, CEO of the Illumination Foundation, where teams are trained to work with the chronically homeless. “The ultimate solution is permanent supportive housing. When we interact with someone, we need to provide immediate relief and then we sit down to assess each person and come up with a plan to give them better quality of life.”

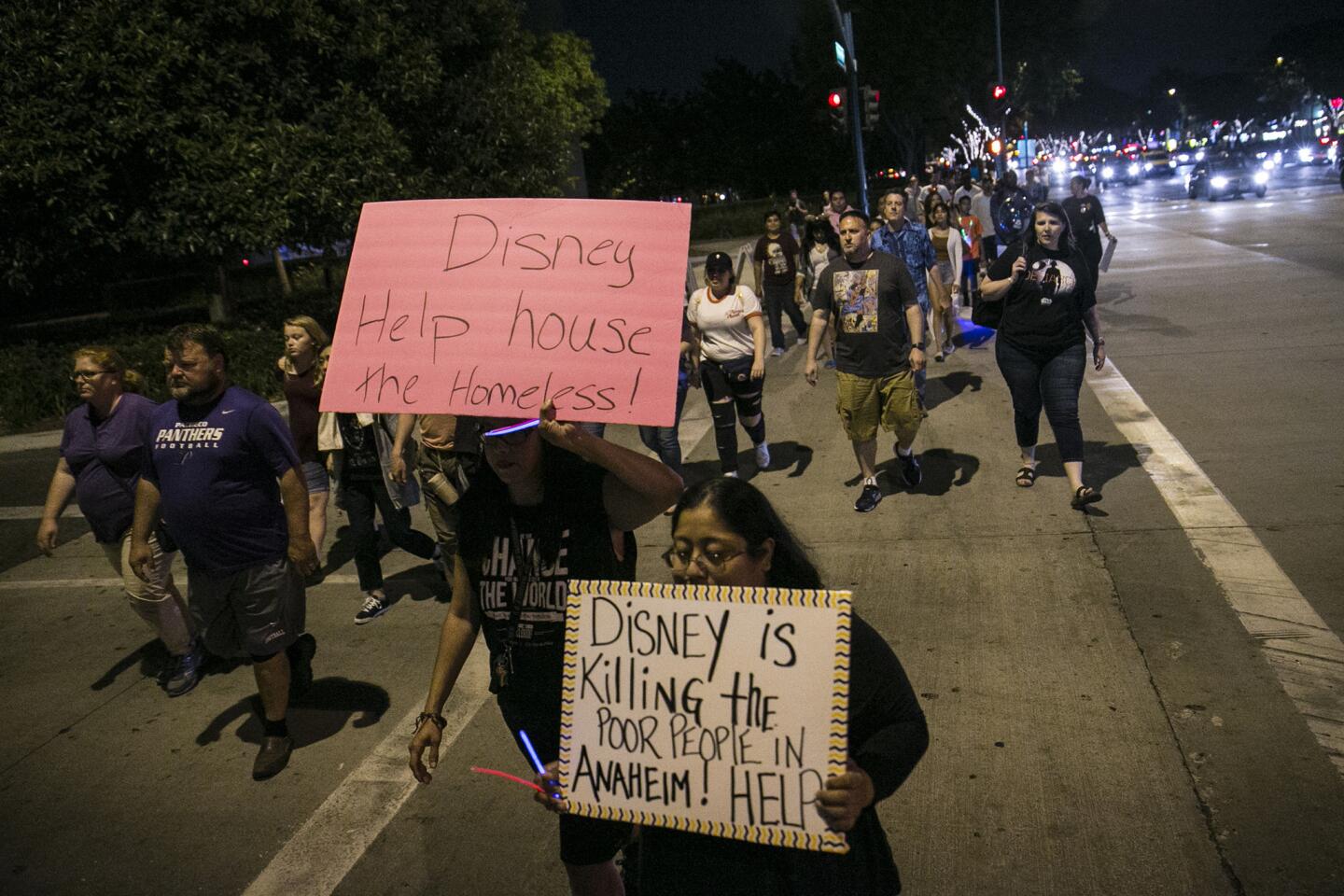

“In this area, those that have the power are trying to push the homeless out of sight — but the number one thing we have to remember — you can’t really deter people from being homeless because they’re not homeless by choice,” added Eve Garrow, a homelessness policy advocate at the ACLU of Southern California. “It’s not their fault. And if we don’t speak up for them, who will?”

To Jackson, a native of Compton, Anaheim’s move was cold.

“When we have a few dollars, we can’t even enter the store to buy a piece of food,” he said. “Some people thought the bus stop would be a good place to crash. No one welcomes us because of who we are and how we look. They have no clue how we ended up here, they just judge.”

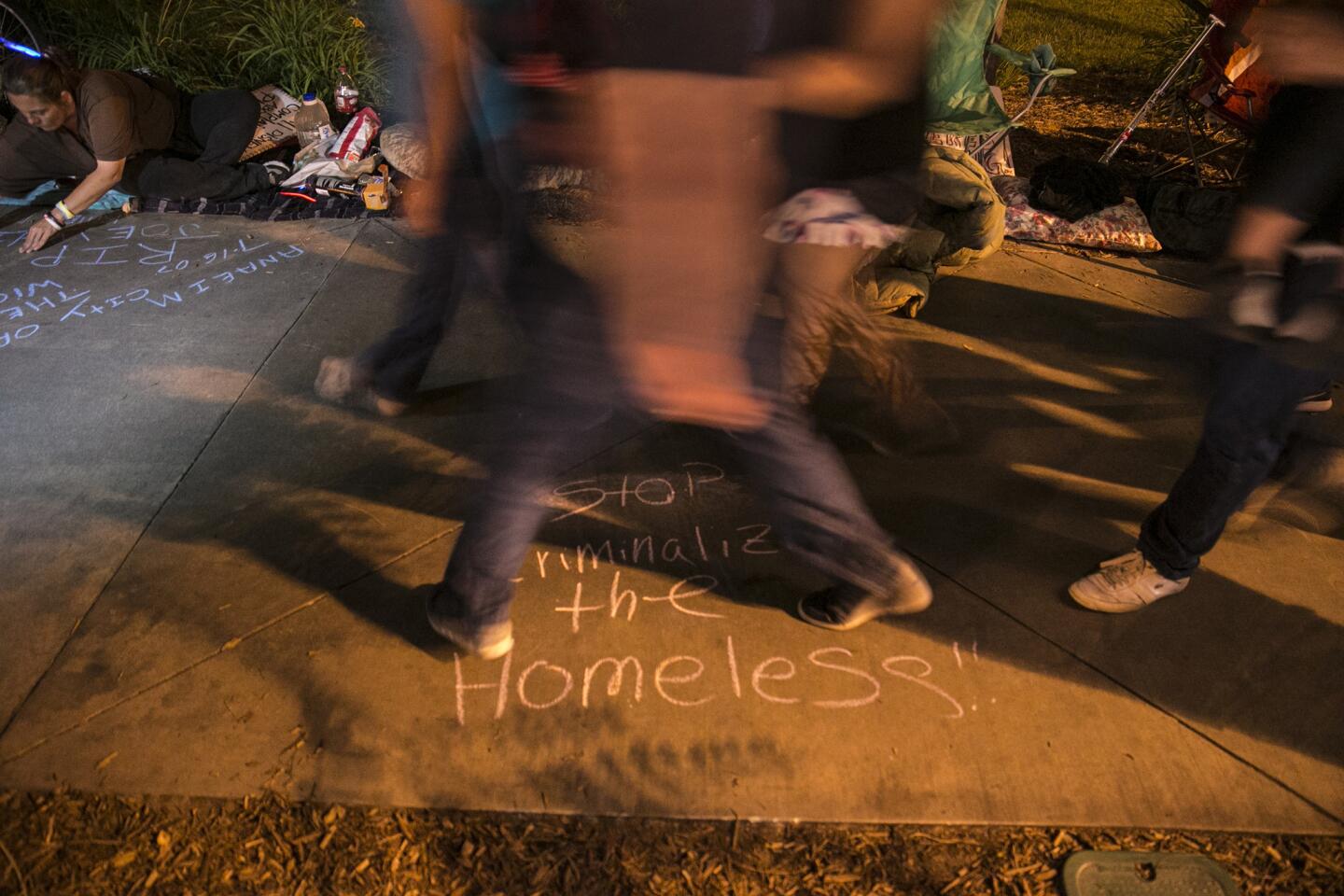

‘We’ll just stretch out on the concrete’

Paul Hyek, 67, a former handyman from Detroit who ended up homeless, said Anaheim was just trying to “show a good image to outsiders.”

“We’ll just stretch out on the concrete. That’s the way we are — we improvise.”

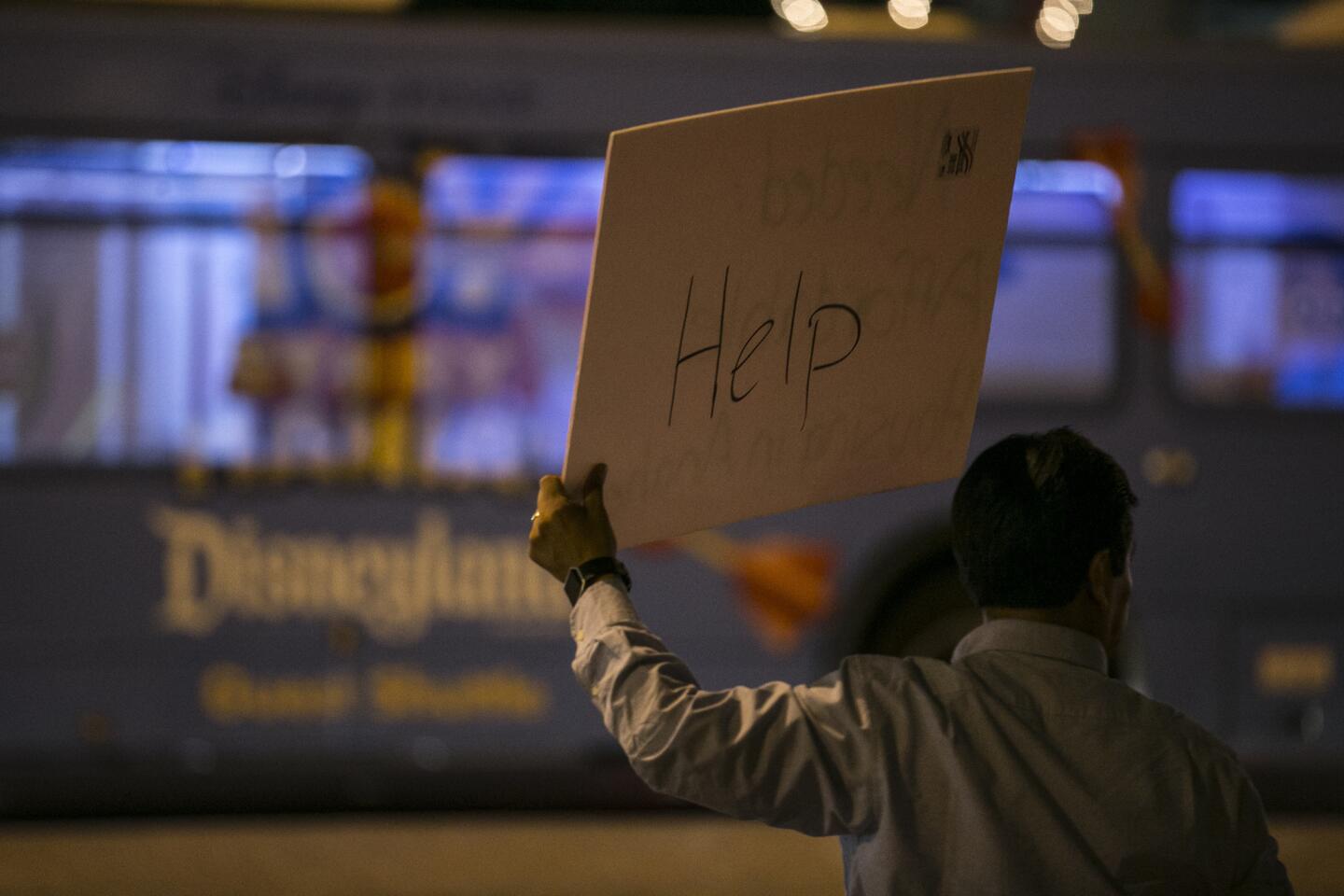

On Friday night, some homeless activists planned a protest outside Disneyland. A spokesperson for Disneyland declined comment.

Anaheim officials said the city has a large network of programs to help the homeless — a population estimated at nearly 800 — by guiding them to shelters, health and mental health resources, in partnership with local agencies.

“You see that sight, you might be intimidated,” Lyster said. “With tens of thousands of workers in the resort district — and even more visitors — it’s a balancing act to care for everyone.”

Lyster said Anaheim intends to bring back some form of seating to the affected bus benches. The options include stools or movie theater or stadium-type seating with armrests, which could not be used for sleeping, he said.

Some visitors to Disneyland said they appreciated the reason Anaheim removed benches.

“It’s a good idea,” says Walton Guerrero, 59, of El Paso. He and 10 members of his family arrived in town for five days packed with Disneyland rides. “This is a tourist place. We need more security so everyone can come back.”

Pushing a stroller carrying his newest grandchild, 4-month-old Samuel, Guerrero said: “We need to feel like we can bring older people and younger people here. We don’t want the kids to be exposed to bad activity.”

Tourists ‘expect everything nice and shiny’

Angelo Newsome, 42, a science teacher from Brooklyn, said removing benches “is happening in our neighborhood too. It’s the same around New York City. But punishing local communities for the actions of the homeless, who are not to blame, seems unfair.”

His partner, Patricia Desormau, looked across to a green bus stop fronting a strip mall, where some men kept watch over their few belongings.

“They’re probably hoping the homeless will relocate themselves,” she said. “But how will they do that?”

Desormau, 39, said it makes sense that people without homes would be drawn by a place like Disneyland, where tourists with discretionary income swarm.

“This is the spot to seek handouts or aid. I would like to see more people or agencies stepping up to offer mental assistance,” the travel agent said. “Not everyone ends up on the streets on purpose.”

As he waited for the bus, Mark Ramirez, a Goodwill employee, said he had mixed feelings about Anaheim’s action.

“I kind of feel bad for them, having to struggle,” the 21-year-old Garden Grove resident said of the homeless. “But I also see it from the city’s point of view. They have to clean up because this is right outside Disneyland. They don’t want the tourists to see this when they visit and expect everything nice and shiny.”

Victor Gutierrez, who roamed Arizona for 12 years, is now transitioning from the streets to sleeping in an old car. At 43, he found a job building stages for public events, starting his shift every day before the crack of dawn.

“I used to sit on these benches overnight and socialize, while waiting to enter work,” he said. “There’s no public transportation that early, so what’s wrong with people hanging around the bench?”

Nearby, a young man napped on a canvas tote bag, sprawled on the urine-stained ground.

“They didn’t solve the problem by taking away the seats,” Gutierrez said, pointing to the sleeping man. “Remember, a bus shelter is a shelter. Period. It gives us shade and it protects us.”

Twitter: @newsterrier

ALSO

L.A. took their water and land a century ago. Now the Owens Valley is fighting back

L.A.’s Mexican American cultural center begins to blossom after a rocky start

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.