He was the pride of East L.A. when he won Olympic gold. Now, he’s accused of molesting a young boxer

When Los Angeles hosted the 1984 Olympic Games, few stories were more satisfying for the hometown crowd than Paul Gonzales’ triumph in boxing. The oldest of eight children raised by a single mother in a Boyle Heights housing project, the 20-year-old light flyweight beat gang violence, poverty and a last-minute broken hand to take gold.

As the national anthem played, Gonzales, the first Mexican American to win a gold medal, clenched a small American flag in his bandaged fist and fought back tears.

“Ten years of struggle, pain and I’m here,” he told broadcaster Howard Cosell.

Many on the Eastside and beyond saw their own lives in Gonzales’ hard-won victory, and even after his boxing career faltered, he remained an inspirational figure. The man sometimes called “the prince of the barrio” was regularly invited to give motivational speeches to schoolchildren, and a fading mural of him in boxing trunks adorned an East L.A. wall.

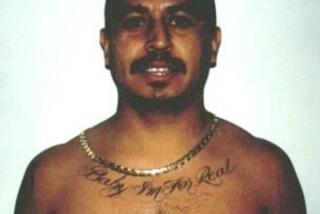

His reputation as a community hero was rocked this week when prosecutors charged the 53-year-old with molesting an aspiring young boxer. A detective overseeing the case said the 13-year-old girl trains at the county-run boxing club in East Los Angeles where Gonzales worked.

Lt. Todd Deeds, with the sheriff’s special victims bureau, said investigators have no specific information that Gonzales molested others, but said given his extensive contact with youth, “we are very concerned that there are more victims out there.”

Gonzales was arrested Dec. 29 and is being held at Men’s Central Jail in lieu of $545,000 bail. He is charged with eight felonies, including four counts of committing lewd acts on a child and possession of child pornography. He faces up to 18 years in prison.

A woman who answered the door at Gonzales’ Montebello residence said she had no comment. The public defender’s office, which is representing him, declined to speak about his case.

Longtime associates said they were stunned by the allegations. Former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a City Terrace native who appeared at community events with Gonzales and previously described him as a friend, called the former boxer’s arrest “shocking and disappointing.”

“My first thought was for the kids that are inspired by role models and whose trust was betrayed,” he said.

World Boxing Council President Mauricio Sulaiman, whose organization presented Gonzales with a community service award a few years ago, said, “He was always kind, always smiling, always working for boxing and for kids.

“I definitely hope there’s a misconception or misunderstanding,” he added.

Olympic teammate Henry Tillman, who won the heavyweight gold medal in 1984, described himself as “sick about” the allegations.

“It’s a sad situation. Paul’s like a little brother to me,” Tillman said.

Gonzales was introduced to boxing at 12 by Al Stankie, an LAPD officer who met him while breaking up a street fight and invited him to box at a community gym. Gonzales eventually moved in with Stankie’s family, and Stankie became his full-time trainer.

“Wow. I can’t believe it. I need to sit down,” the 77-year-old Stankie said Friday after learning of the charges from a reporter.

Stankie and Gonzales became known as “the cop and the kid” during the Olympics. Their heart-warming relationship and the boxer’s hard-knock backstory attracted notice that was rare for small fighters like Gonzales, a light flyweight who weighed in at 106 pounds.

The U.S. team that year was packed with talent, including future world champions Evander Holyfield, Pernell Whitaker, Meldrick Taylor and Mark Breland. The Americans won nine gold medals.

Gonzales seemed destined to parlay his Olympic fame into a blockbuster professional career. He was paid $40,000 for his 1985 professional debut, a fight at the Hollywood Palladium televised live on CBS, and subsequently topped cards across the country.

“I wanted Paul because he had that cachet of being a gold-medal winner and we could promote that as not just another warm body; club promoters need a certain angle: ‘Here’s the gold-medal winner,’ ” said longtime Orange County fight promoter Roy Englebrecht, who brought Gonzales to the Irvine Marriott for two 1988 cards. “He sold tickets.”

But Gonzales’ career faltered. There was a falling out with Stankie, later mended, and a series of broken bones that hindered his speed and strength in the ring. He retired in 1991.

“History will reflect that Gonzales’ dream fell several punches short. He never became a millionaire, or wore a world championship belt,” The Times wrote in 1994.

Gonzales had to watch as Oscar De La Hoya, another Mexican American from East L.A., used his own gold medal — in Barcelona in 1992 — to achieve the boxing superstardom that had escaped Gonzales’ grasp. It ate at him.

“People say, ‘Do you know Oscar?’ and I say, ‘Yeah, he’s my shadow,’ ” Gonzales told The Times in 1994. “That’s what he is, my shadow. Paul Gonzales paved the road for a lot of Hispanics. Now, a lot of them are getting what I should have gotten.”

Gonzales made unsuccessful runs at a City Council seat in 2002, 2003 — when he garnered just under 4% of the vote — and again in 2005. But boxing and young people were always his priority. He taught for many years at the Hollenbeck Youth Center, where Stankie had trained him for the Olympics. Into the mid-1990s, children would line up there for his autograph.

Ten years ago, the county Department of Parks & Recreation hired Gonzales as a coach at Eddie Heredia Boxing Club on Olympic Boulevard. He was paid about $60,000 a year, according to public records, and worked with aspiring boxers between the ages of 8 and 19. The club has an open-air facade along a busy street, where anyone, including adults, can train in personal fitness and boxing.

“We’re kinda like our own little island,” Gonzales said of the gym in a 2014 parks department video posted online. For many youths, he said, the free program was an “outlet from the streets.”

The sheriff’s investigator, Deeds, said Gonzales met the 13-year-old last year when she began attending an after-school program at the gym. He said he “groomed” her and then entered into a sexual relationship with her.

She was molested between May 1 and Aug. 9 of last year, according to the felony complaint. A family member went to authorities about Gonzales in December, Deeds said.

The parks department said in a statement that it was cooperating with the sheriff’s investigation. Terry Kanakri, a department spokesman, said Gonzales was still employed by the county, but not being paid. He said that at least two employees were present at the gym during working hours and that when youths travel to box in tournaments, they are accompanied by their parents. Kanakri said he did not have information about whether Gonzales traveled on any of the boxing trips.

Stankie, Gonzales’ boxing mentor, said he had visited Gonzales at the county boxing club several times and never saw any inappropriate behavior.

“I’m not going to lie to you. He loved girls, but they were all women, not babies,” Stankie said. He said that someone called his home from the county jail last week. “I wasn’t here to take it. It must’ve been Paul.”

Interviewed three years ago for a British sports program, Gonzales showed off a mural featuring him and other athletes on City Terrace Drive and noted that his image was free of graffiti.

“It’s not touched, which is an honor, a great respect to me,” he told an interviewer.

By Friday afternoon, someone had used black spray paint to cover his part of the mural and scrawl Spanish obscenities next to it.

Follow @latimesharriet, @mayalau and @latimespugmire on Twitter.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.