Are L.A. County deputies still ‘dumping’ vulnerable people? An injured artist’s case revives concerns

- Share via

Stafford Taylor was his usual self, vigorous and sharp-minded, when he left a friend’s party late on the Fourth of July.

But sometime after, the 64-year-old Malibu artist and master carpenter was attacked and left wandering Pacific Coast Highway. He didn’t receive medical attention for hours, his family says, because the sheriff’s deputies who picked him up left him at a day laborer’s center. Nearly half a year later, he is still suffering from brain damage and has difficulty speaking.

His family is convinced that deputies thought he was homeless.

The Taylor family filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Los Angeles County and the Sheriff’s Department this fall, claiming they showed a “deliberate indifference to medical needs.”

The suit alleges that deputies from the Lost Hills station “doomed” Taylor to suffer severe injuries before he was hospitalized, causing damage that will require medical attention for the rest of his life.

“The Sheriff’s Department, or at least certain deputies, are treating people like throwaway people,” said Arnoldo Casillas, the family’s attorney.

A decade ago, Los Angeles faced national scrutiny for a series of highly publicized cases in which police and hospitals dumped homeless people — often in downtown’s skid row.

While patrolling the area in 2005, a Los Angeles police captain saw sheriff’s deputies dump a man near San Julian Street. The deputies said they were taking the man to a mission, but the captain said there wasn’t one nearby. LAPD officers at the time also reported seeing patrol cars from four other agencies — El Monte, Pasadena, El Segundo and Burbank — dropping off homeless people downtown.

A year later, a video circulated showing a dazed woman wandering skid row in a hospital gown and “60 Minutes” did a segment on patient dumping in L.A. The city sued several hospitals and the issue faded from national focus.

But the practice hasn’t disappeared and isn’t confined to skid row.

In January, L.A. City Councilman Joe Buscaino criticized the Sheriff’s Department for dropping off a homeless man along a street in San Pedro, which is outside of their jurisdiction. The councilman learned about the case from a resident, who recorded video as a deputy dropped off the man, who appeared agitated and flailed as he walked down the sidewalk. “Hey, thanks for dropping him off!” the resident shouted sarcastically as the deputy drove away.

The Sheriff’s Department says deputies were “performing an act of compassionate service” by taking the man to a bus stop at his request. But the Taylor family cited the San Pedro case in their lawsuit, arguing it shows a pattern.

In July, city and county prosecutors announced a $550,000 settlement with Silver Lake Medical Center, which authorities say violated the law by dropping off potentially hundreds of patients at bus and train stations — the eighth such settlement with a healthcare facility in the past five years.

“People make assumptions and, unfortunately, instead of taking them to the hospital, they dump them off on a shelter or in [Taylor’s] case a day laborer’s center,” said the Rev. Andy Bales, who heads the Union Rescue Mission on skid row.

Taylor left the Malibu party around 10:30 p.m. At dawn the next day, private security guards at a home near Geoffrey’s restaurant noticed him, half-naked and confused, wandering from car to car. The guards called sheriff’s deputies, who picked up Taylor and dropped him off at the Malibu Community Labor Exchange about five miles away. Taylor had suffered severe head injuries and the incident is still under investigation, sheriff’s officials said.

His wife, Terry, says the deputies must have assumed her husband was homeless.

“How could they not see he needed help?” she said.

Oscar Mondragόn, who directs the labor exchange, said several workers have told him that they’ve seen deputies dump people outside the exchange in the past.

Mondragόn said he saw Taylor slumped on a bench outside the exchange when he arrived for work at 7 a.m. on July 5. He must be sleeping, Mondragόn thought. Eventually, he wondered if the man might be sick so he tapped his shoulder and asked, “Sir, are you OK?”

“He said, ‘yes,’” Mondragόn said. “I didn’t know how bad he was.”

It wasn’t until 10:20 a.m. — five hours after deputies left him at the hiring center — that a woman who was waiting to find work called 911. An ambulance transported Taylor, who was semi-conscious, to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, where he was admitted as “John Doe” — a factor in his family not knowing where he was for 36 hours.

Terry had spent the Fourth of July in the Midwest visiting family, returning two days after the assault to find her husband in a hospital bed with a deep purple bruise ringing his swollen right eye. He could only breathe through a plastic tube inserted into his windpipe. Doctors told her he might die unless part of his skull was removed to alleviate pressure on his brain.

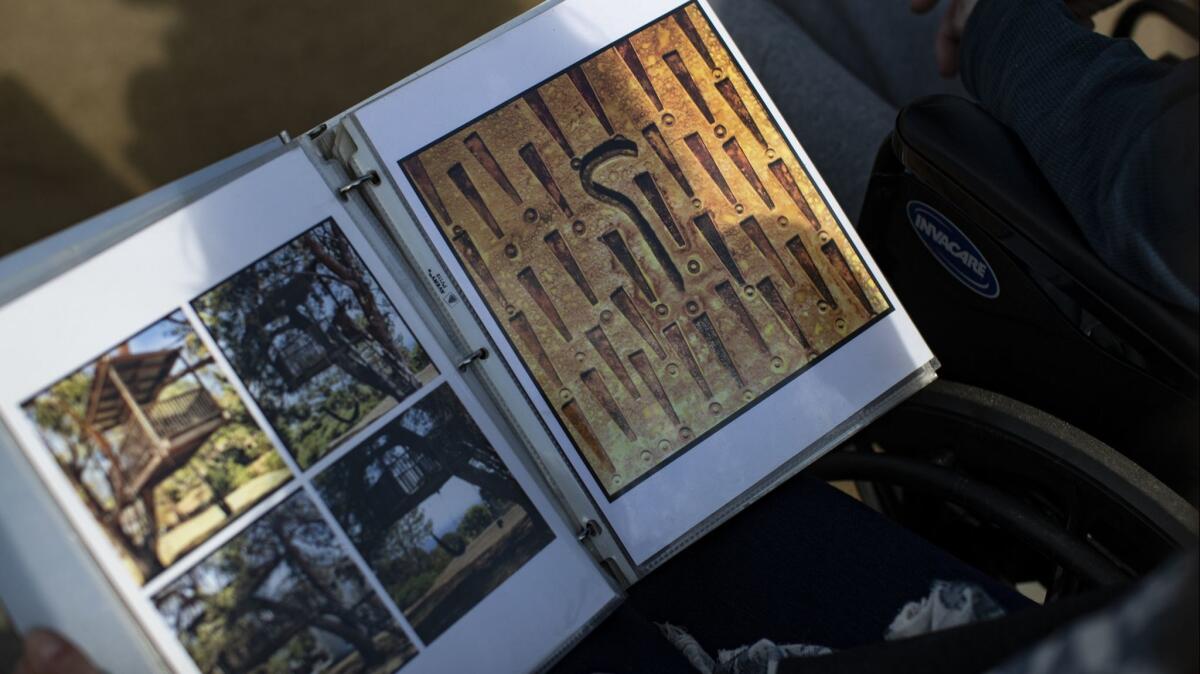

She thought about her husband’s work — about the intricate tree house he built in the backyard of Robert F. Kennedy’s daughter’s home and about his detailed pen drawings.

“Will he ever draw again?” she wondered.

The Sheriff’s Department doesn’t deny that deputies dropped Taylor at the labor exchange that morning. But in a July press release about the assault investigation — which remains ongoing — sheriff’s officials said it was “unknown at this time when or how the victim sustained his injuries.”

In a written statement, spokeswoman Nicole Nishida said the department is reviewing the incident “as it relates to policies and procedures.”

We “care about the well-being of Mr. Taylor,” Nishida said. “We have followed up with the family at the hospital and offered assistance to them during this challenging time.”

It’s still hard for Terry to believe that it was deputies who left her husband that morning. She ran a preschool in Malibu for years and once had sheriff’s officials come speak to her students.

“I’ve taught young children that we can count on them,” she said.

She doesn’t fixate on the deputies, though, or on the person who attacked her husband. She prefers to think about the undocumented woman who called to get her husband an ambulance that morning.

“She saved his life,” Terry said, as tears filled her eyes. “The swelling would’ve killed him.”

Sometimes she thinks about how the couple had planned to move to Wisconsin to be closer to family and how she had let their insurance lapse during those crucial few months before the attack, gambling on the fact they’d soon be eligible for Medicare. In the hospital, Terry said, she talked to him or sang him songs, hoping he could hear.

Because of the brain damage, Terry said, he lost the ability to fully express himself or understand. But recently, she has noticed improvements.

During one visit, an occupational therapist brought markers and a big sheet of paper to the hospital room. Taylor switched between blue and black markers, drawing a series of concentric, squiggly rectangles.

It was reminiscent, his wife said, of a signature geometric design from many of his past drawings.

One afternoon, before moving to a rehabilitation facility in Downey, Taylor sat quietly on his hospital bed, listening to the dull beep of a monitor checking his heart rate and oxygen.

When Casillas walked in, Terry asked her husband if he remembered their attorney.

“I hear you’re eating again!” Casillas said. “You feel good?”

“I do well,” Taylor said, glimpsing over at Terry for reassurance. She nodded.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.