Mystery solved: Remains of girl in forgotten casket was daughter of prominent San Francisco family

An unmarked casket of a little girl was uncovered in San Francisco last year. (May 11, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here)

- Share via

Her remarkably well-preserved body was discovered a year ago in an unmarked metal casket in a wealthy San Francisco neighborhood.

She was barely 3 when she died and was interred in a long-forgotten cemetery more than a century ago. When workers discovered her elaborate coffin beneath a concrete slab, there were no markings or gravestone to say who she was.

Over the last year, as the casket rested in a new grave in Colma, a team of scientists, amateur sleuths and history buffs worked tirelessly to solve the central question in this Bay Area mystery: Who was the little girl in the casket?

This week, they announced their answer: She was Edith Howard Cook.

According to the Garden of Innocence, an organization that buries abandoned and unidentified children, the girl’s DNA was matched to that of a descendant now living in San Rafael.

Who was Edith?

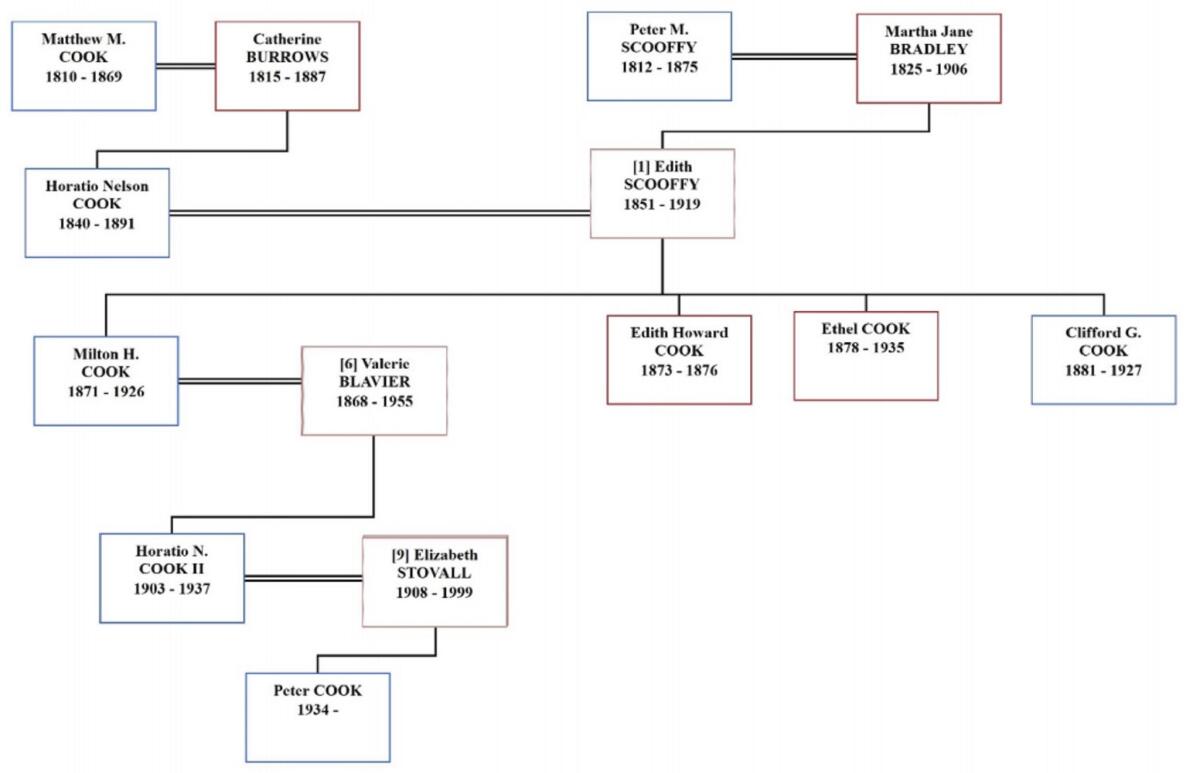

Edith Howard Cook was born in San Francisco on Nov. 28, 1873.

The daughter of Horatio Nelson Cook and Edith Scooffy Cook, she died of marasmus — a form of severe undernourishment — on Oct. 13, 1876, said Jelmer Eerkens, an archaeologist at UC Davis who analyzed Edith’s hair.

Marasmus is characterized by a severe deficiency in nutrients, particularly protein, and can be brought on by viral, bacterial or parasitic infections.

Chemical isotopes showed that in Edith’s last months, she essentially wasted away from malnutrition, he said. There was no evidence that doctors tried to use treatments popular at the time, such as morphine, mercury or cocaine.

The girl’s DNA revealed that part of her lineage traced back to the British Isles.

She was found entombed in an airtight casket that was 37 inches tall. Her curly locks were laced with sprigs of lavender. A rosary and eucalyptus seeds were placed on her chest.

How did researchers know where to look?

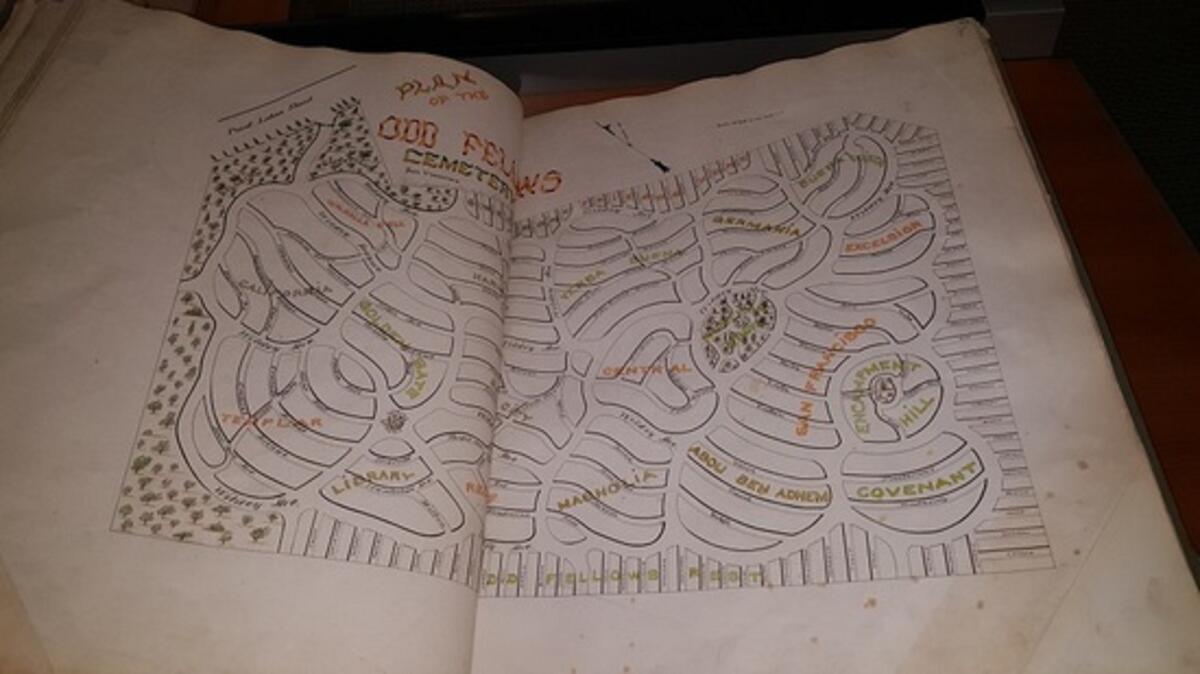

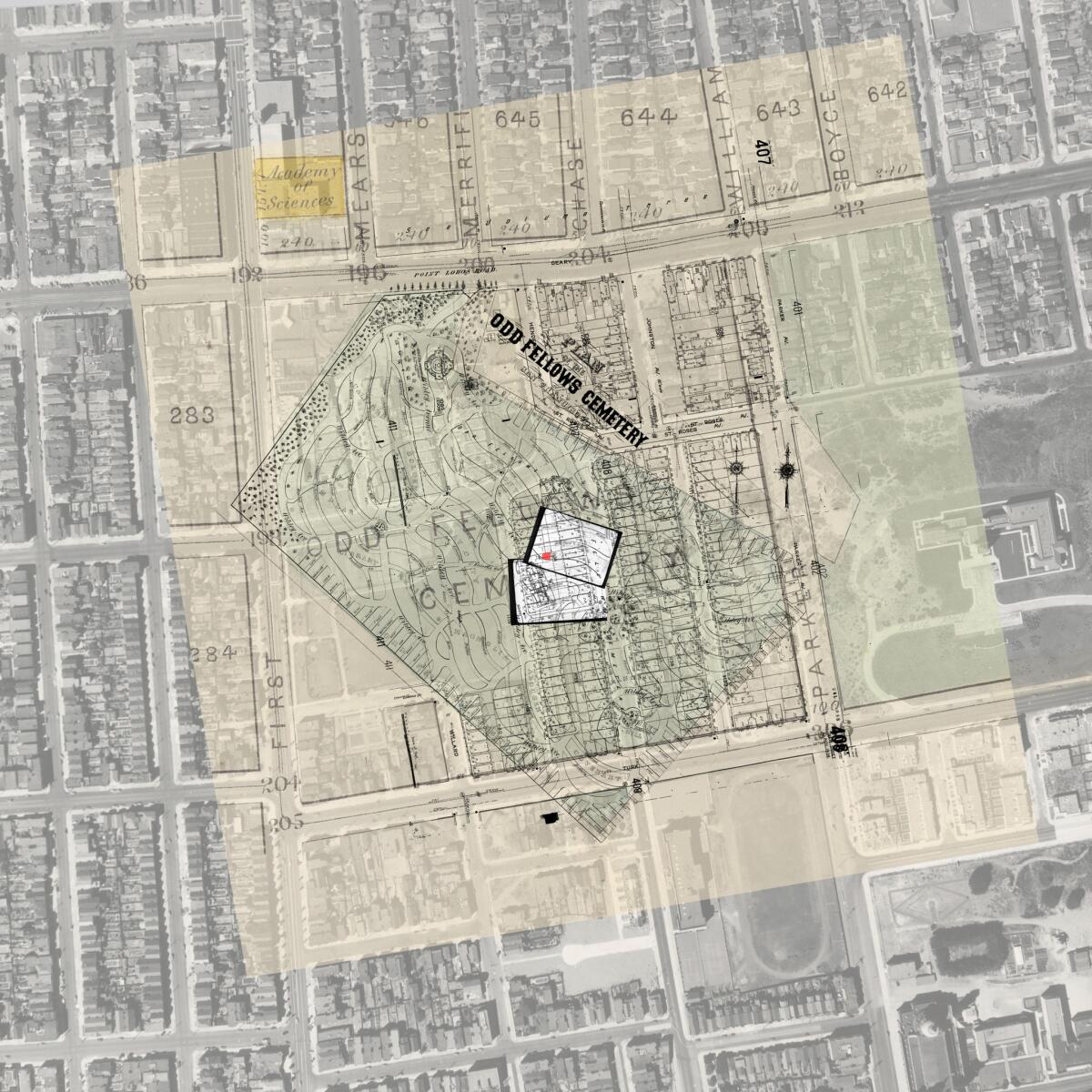

First, they needed a lead. The casket was more than 140 years old and there was no headstone. The team had to find a map of Odd Fellows Cemetery that would show the layout at the approximate time Edith was buried.

A scale plan of the cemetery development in 1865 ultimately was found at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Researchers overlaid the cemetery map onto the neighborhood where the casket was found.

The results narrowed the girl’s identity to two prime candidates. Thanks to the Internet and a culture of open records that existed from the 17th century to the 1960s, amateur genealogists were able to tap centuries of records of censuses, births, marriages, properties and deaths to trace up and down each candidates’ family tree. The whole effort took three people 3,000 hours, said Elissa Davey, who spearheaded the search for Edith’s identity.

“I knew this day would come because I knew we wouldn’t give up on her,” Davey said.

Bob Phillips, a 65-year-old retired federal employee from Seattle, said he read about the casket’s discovery online and emailed Eerkens, the UC Davis professor, to volunteer his genealogy skills.

Phillips traced Edith’s family back to the 1600s and then up to modern times. He found someone he believed to be a living grandson of Milton Cook, Edith’s older brother.

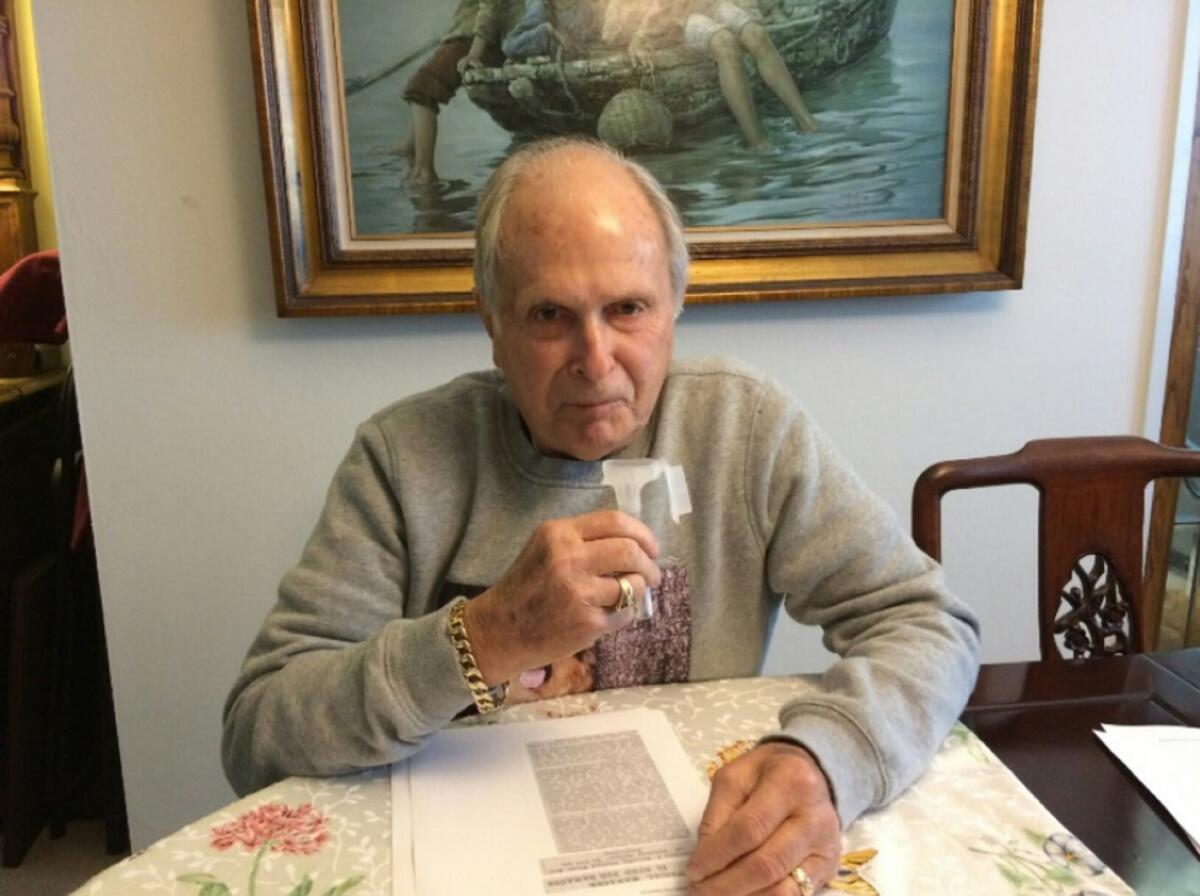

But the descendant, Peter Cook, 82, didn’t know his family tree on his father’s side back more than a generation. Some of the names Phillips mentioned sounded familiar, but there wasn’t enough to confirm that Peter Cook was related to Edith Cook, who would have been his great-aunt.

“In researching the family, particularly when we narrowed our focus down to Edith Cook and her family, you become kind of involved and you’re sort of rooting for it to be Edith,” Phillips said. “You can follow their family on through various articles and census records, and you get a kind of sense of who they were and what their life was like.”

The team met Peter Cook at his home in the fall and took a saliva swab for his DNA.

How did they confirm it was Edith?

Using just a handful of hair strands only a few inches long from Edith’s scalp, Eerkens and UC Santa Cruz biomolecular engineering associate professor Ed Green mapped the girl’s DNA and chemical isotopes.

The follicle tissues provided nuclear DNA, which contains genetic information from both parents but is more difficult to harvest, and mitochondrial DNA, which shows only the mother’s genetic information but is in much greater abundance.

Because the girl was in a casket for more than 140 years, only about 10% of the DNA sequenced from the hair belonged to the girl. The rest was mostly fungus or other organisms, Green said.

But he and his students weren’t intimidated — they work with DNA from ancient hominids and woolly mammoths regularly.

“This is an atypical sample in that it’s kind of young — from 1876,” Green said. “It’s kind of an easier sample.”

If Green’s team hadn’t been able to sequence Edith’s nuclear DNA, “we would not have been able to ID the girl,” Eerkens said. “In fact, we probably would have ruled [Edith] out.”

The comparison between Peter Cook’s DNA and Edith’s turned up a 12.5% match along unique genomes that can be identical only along direct descendants, Green said.

He and his students were thrilled with the results.

“It’s unlike a lot of scientific projects where there’s not a prospect of a binary answer like, ‘Yes, this is it,’ or, ‘No, it is not,’ ” Green said. “Most of what we do is open-ended, and progress comes in steps so small you don’t even know you’re making them. It was so special.”

Who was Edith’s family?

Edith was the first daughter and second-born child in the Cook family, who was prominent in San Francisco in the latter 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Scooffy family, on Edith’s mother’s side, was among the first pioneers to arrive in San Francisco at the height of the Gold Rush, said Phillips, the amateur genealogist who helped find the girl’s identity.

Edith’s grandfather was Peter Scooffy, an oyster merchant who immigrated to the U.S. from Greece through New Orleans. There, in 1845, he married Martha Bradley, whose family lineage traces back to the earliest Virginia settlers. The couple moved to San Francisco, where they eventually had Edith’s mother.

On her paternal side, Edith’s grandfather, Matthew Mark Cook, hailed from England and her grandmother from Nova Scotia. The couple had seven children and moved to San Francisco years after the Scooffy family.

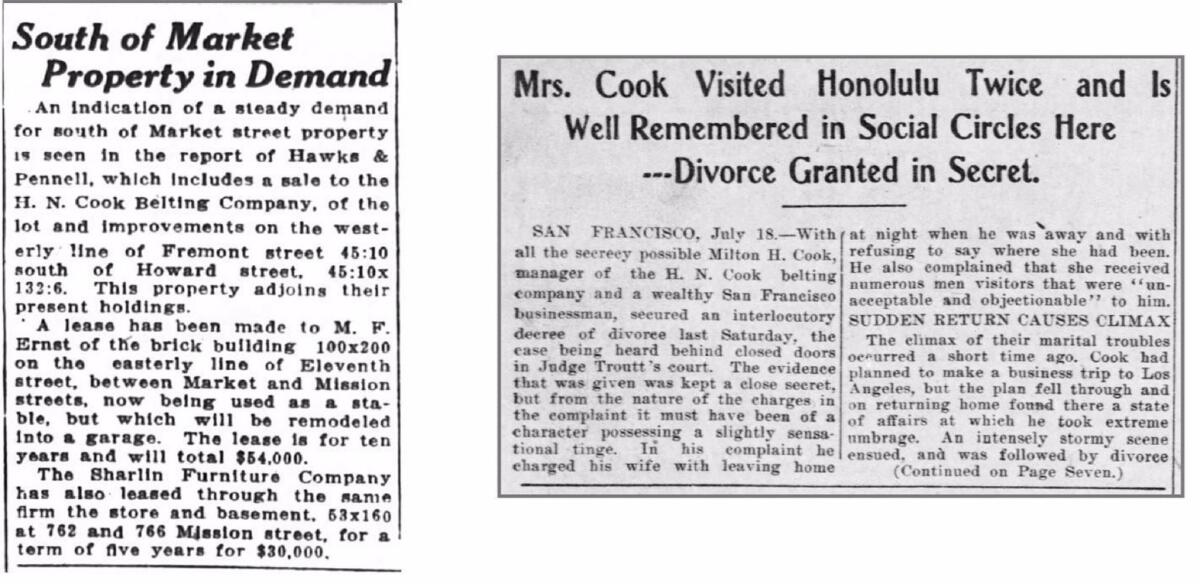

Among their children was Edith’s father, Horatio Cook. Together, Matthew and Horatio Cook established the family business, M.M. Cook & Son, a leather belting and hide-tanning business. After Matthew died, Horatio Cook continued to run the company with his sons (Edith’s brothers,) Milton and Clifford, and renamed the business H.N. Cook Belting.

The company remained in existence until the 1980s, when it merged with Hoffmeyer Belting and Supply Co. in San Leandro. The new business was then bought by San Diego Rubber Co. Inc. in 1994 and renamed Hoffmeyer Company Inc.

Though Edith wasn’t around to see it, her family became part of the “jet set” crowd in San Francisco in the early 20th century, Phillips said.

Edith’s younger sister, Ethel, was born after Edith died, and she grew up to become a San Francisco socialite, Phillips said.

In the book “Inventing Elsa Maxwell: How an Irrepressible Nobody Conquered High Society, Hollywood, the Press, and the World,” about a middle-class woman’s climb into the social strata, the author recalls a news clipping about Ethel Cook’s “secret” marriage to a prominent New Yorker.

The news clipping described Ethel Cook as the “reigning bell of San Francisco,” who once was “made famous by Grand Duke Boris of Russia, who drank a toast with champagne out of one of her slippers at a banquet and declared that she was the most beautiful American woman he had ever seen.”

Today, the family continues to thrive, according to Peter Cook.

Cook has eight children, 13 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren. Already thoroughly knowledgeable about his wife’s and mother’s families, the phone call he received last fall regarding the mystery girl buried in San Francisco only expanded his family pride.

“I tried to trace my father’s side, and I got to my father and that was it,” Cook said. “All of a sudden they came with information on divorces, my grandfather went back to France on the USS Normandy. … Oh I think it’s fantastic. Jelmer [Eerkens] has got me back into the early 1700s. That really makes me feel good.”

Where was Edith found?

Edith Cook’s body was found inside an airtight metal casket beneath a garage in San Francisco’s Richmond District, where the Odd Fellows Cemetery once was located.

The homeowner, Ericka Karner, said the casket was discovered by workers remodeling the home while she and her family stayed with relatives in Idaho.

At least twice in recent years, Karner said, she and her husband have heard the inexplicable sound of children’s footsteps running in the home. The couple have two daughters, but the children were sleeping or not where the steps were heard in both cases, she said.

Even after Edith’s body was found, disinterred and moved, the spooky steps still could be heard, Karner said.

“We had a couple of contractors, on separate occasions, who thought they heard footsteps,” Karner said. Each time, the contractors walked through the house looking for a child — possibly a wayward kid who had run into the house from a park across the street — and both times, the contractors found nothing, Karner said.

“I’m not sure where I stand on where the soul goes, but my hope is … if she was still hanging around here figuring out where she needs to be, that her being identified will give her a little peace and she’ll potentially go off and be with her family, where she needs to be,” Karner said. “We felt that if anything, she was a friendly spirit. If she wants to stay and play, we’re totally OK with that!”

Why was Edith buried there?

According to historians, when San Francisco was in its infancy, residents and businesses coalesced around San Francisco Bay. The dead were buried in what is now the financial district.

But then came the Gold Rush of 1849, which flooded the city with new residents, new illnesses and death. Bodies in the financial district were exhumed and relocated west, closer to the ocean, to make way for the mass migration.

By the late 1880s, there were dozens of cemeteries in San Francisco, and most were full. Officials and developers deemed the burial grounds to be more valuable to the living, and they launched a decades-long campaign to evict the dead.

City crews and cemetery workers hauled hundreds of thousands of corpses south to what is now Colma. Today, the city has about 1,500 living residents and more than 1.5 million bodies underground, including such historic figures as Wyatt Earp and William Randolph Hearst.

An email last summer from one of Edith’s researchers in Montana explained why so many bodies were missed during the mass transport of graves to Colma a century ago.

“Bulldozers weren’t involved in the removal process,” the researcher wrote. “The surface land was stripped bare at least seven years before actual digging began. The removal contractors placed string lines in an east-west orientation, spaced where experience told them the most graves would be intersected. Experts moved along those string lines, probing with hardened brass rods at set intervals. They could literally predict by feel and experience whether there was a casket, a collapsed grave, ashes or no grave at all below. Workers dug only where they marked and as deep as they marked. Everything was done by hand.”

Where is Edith now?

Edith Cook was buried under the name “Miranda Eve” on an overcast June morning last year in Colma. Her pseudonym was picked by Karner’s daughters because the girl had been discovered at their residence. Her original casket was put inside a slightly larger cherry wood-paneled coffin with handles on each side and two bouquets of white flowers on top.

Her heart-shaped granite headstone read:

Miranda Eve

The child loved around the world

“If no one grieves, no one will remember.”

The other side was left blank just in case true identity was ever discovered.

Everyone who helped in finding Edith’s identity had their own reasons for making sure the slate didn’t stay blank forever.

“One of the most amazing things about this: Everyone was working pro bono on this,” Green said. “People wanted to solve this. It was infectious.”

A second memorial service for the girl is scheduled for 11 a.m. June 10 at Greenlawn Memorial Park in Colma.

Since Edith’s identity search began, the remains of three other people buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery location have been discovered and need to be identified, Davey said.

For breaking California news, follow @JosephSerna on Twitter.

ALSO

A Muslim father and son engrave the headstones at one of India's oldest Jewish cemeteries

Overgrown and forgotten, Tacoma cemetery holds a mystery: thousands of unmarked graves

Her toddler suddenly paralyzed, mother tries to solve a vexing medical mystery

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.