Summer programs help prepare minority students for college STEM

- Share via

When Oscar Leong graduated from his Los Angeles high school four years ago, he ranked second in his class, with a 4.4 GPA and a scholarship to Swarthmore College, where he planned to major in astrophysics.

But Leong, the son of Mexican immigrants, struggled his freshman year, working the hardest he’d ever worked to earn just a B- in introductory physics.

His confidence shaken, Leong began to wonder if he was really cut out for Swarthmore. He considered transferring, or at least dropping his major.

“I told myself, ‘I’m not as smart as I thought I was,’” he said.

Leong’s experience reflects a troubling reality in American higher education: Despite the strong emphasis in recent years on encouraging students to pursue science and technology fields, little progress has been made to change the makeup of those receiving college and graduate degrees in those fields.

Students from underrepresented minority groups, including blacks, Latinos and Native Americans, complete degrees in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) at lower rates than white and Asian American students, data show.

At the national level, the UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute, which surveys college freshman annually, has found that as many black and Latino students intend to pursue STEM majors as their white and Asian American peers. However, just 18% of black students and 22% of Latino students who started out with STEM majors in 2004 completed bachelor’s degrees in that same field within five years, compared with 33% and 42% of white and Asian American students, respectively, the Institute found.

Although blacks and Latinos make up 11% and 15% of the overall workforce, respectively, they represent only 6% and 7% of the STEM workforce, according to a 2011 Census Bureau report.

With minorities expected to become a majority of the U.S. population in the next 30 years, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics forecasting the addition of 1 million STEM jobs by 2022, some economists say expanding diversity in the fields is a workforce necessity.

“The competencies embodied in STEM majors are in high demand and highly valued throughout the economy,” said Nicole Smith, an economist at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, noting the comparatively high starting salaries and lifetime wage premium for STEM jobs. But there’s “not a commensurate rate of interest by students in completing STEM majors,” Smith said.

Minority and low-income students face a number of hurdles in completing such degrees, including the quality of high school instruction, limited access to advanced science, math and technology courses, a lack of guidance on how to navigate college and social stigma, said Kevin Eagan, director of the Higher Education Research Institute.

Now, across the country, academic programs are working to expand access and improve success. The South Central Scholars Summer Academy, a college-preparation program that Leong attended in the summer of 2012, is one of a handful of programs in Southern California focused specifically on helping underrepresented minority students graduate in STEM majors.

The seven-week summer program targets promising high school seniors and college freshman with instruction in precalculus or calculus as well as English, in addition to professional development and mentoring. Freshman can also opt for chemistry, computer science and quantitative reasoning. The courses — a mix of interactive lectures and small-group workshops — are taught by USC faculty on campus and mirror the curriculum and rigor of freshmen classes, but with more support.

“We’re really trying to bridge this gap between underperforming high schools and elite colleges,” said Joey Shanahan, executive director of South Central Scholars.

Preliminary results suggest the program is succeeding. According to the program’s internal data, 72% of students who attended the Summer Academy in 2012-2015 have graduated in STEM fields or are in college and on track to do so.

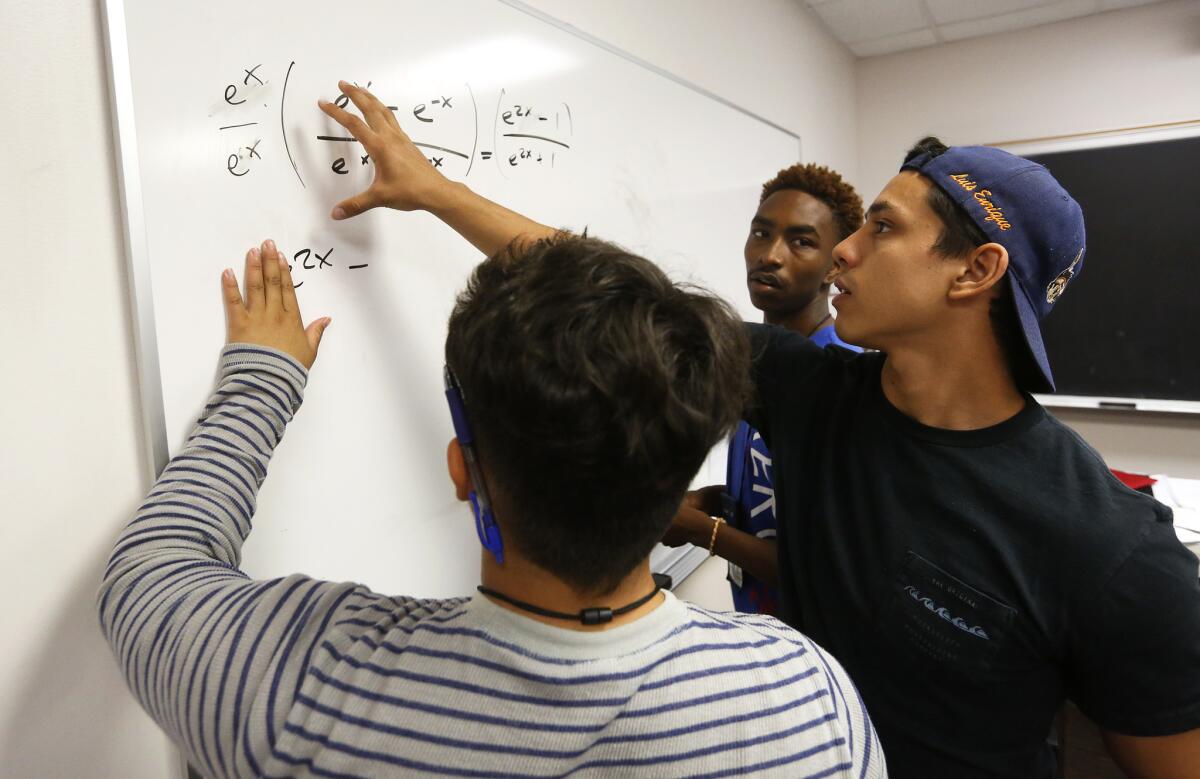

On a recent afternoon, David Crombecque was giving a lecture to seniors on graphing polynomial functions — part of a math curriculum that spans algebra, trigonometry and calculus.

As the lecture hour neared its end and the material became more complicated, the room turned quiet, with fewer students answering Crombecque’s questions at the board. But in the small-group session that followed, the students became animated again as they helped one another and tested solutions on the board with a teaching assistant.

Crombecque, a math professor at USC, is a stickler for holding students to high standards. While the Summer Academy math courses are designed to fill knowledge gaps, “it’s not so much about the content. It’s about the rigor,” said Crombecque, noting that for many students, his class may be the first time success in school doesn’t come easily. “I’m trying to give them a hint of what it’s going to be like in college.”

Camreon Lyons, a senior in Crombecque’s class who wants to be an OB/GYN nurse practitioner, said that before attending the Summer Academy she didn’t study much for math. Now, if she doesn’t finish a worksheet in class, she’ll finish at home. “If you keep looking at the topic, it gets easier,” Lyons said.

The skills Lyons and her fellow students are learning — such as developing a sense of resiliency — are essential for succeeding in challenging science programs in college and beyond, education researchers and economists said.

Extra time spent in a rigorous math class helps students, too. A 2016 review by the U.S. Department of Education found that the number and rigor of STEM courses taken in high school were strong predictors of STEM success in college.

Leong, for example, attended Cathedral High School, a private all-boys Catholic school near Chinatown, and took AB Calculus, the highest math course offered at the time — but not the most rigorous Advanced Placement calculus course offered by the College Board. Similarly, Leong took an AP physics course on mechanics, but his school didn’t offer the subsequent course in electricity and magnetism.

At Swarthmore, Leong was surprised other students in his introductory physics classes were already familiar with the material. “This was stuff I didn’t think was in high school,” he said. “We don’t know what we’re up against until we get to these schools.”

That’s what the Summer Academy and other programs at universities such as Cal State Dominguez Hills have been aiming to change.

At the Dominguez Hills campus, where a majority of undergraduates are black or Latino, only 13% of students who entered in 2009 with a STEM major graduated in that same field within six years, according to Cal State University data.

STEM faculty across departments designed a program, FUSE (for First-Year Undergraduate Student Experience), to increase retention of STEM majors. The program includes a two-week summer boot camp to help students prepare for their first college-level STEM courses, additional support in freshman chemistry, computer science and math, and peer and faculty networking.

The program launched last fall and there is no data yet on its effectiveness. “The ultimate measurement will be did the students come back for a second year,” said Matthew Jones, chair of the math department.

Grades in entry-level courses often serve as a signpost to students about whether to continue in a field.

“If you do poorly your first quarter … it really impacts your GPA, and it’s very demoralizing and you lose your self-confidence,” said Tama Hasson, a UCLA professor who oversees an academic support program for science majors from underrepresented backgrounds.

Leong was consumed with self-doubt after those early physics courses at Swarthmore. But he did well in calculus. That got the attention of math professor Cheryl Grood, who encouraged him to consider a math major and to apply for research opportunities at Swarthmore, where she offered to supervise him.

Leong took Grood’s advice, eventually winning an award at a national research conference for Latino and Native American scientists. Standing in a room full of successful minority students was “kind of eye-opening,” Leong said, and introduced him to the possibility of a career in math.

Later this month, Leong will begin a Ph.D. program in applied math at Rice University. He said he expects it will be challenging but, unlike his first year at Swarthmore, he doesn’t anticipate having any thoughts of dropping out.

Times staff writer Teresa Watanabe contributed to this story.

Twitter: @agrawalnina

ALSO

‘Liquid Shard’ art installation makes waves in Pershing Square

San Bernardino County reaches resolution with federal government over disabled students

Marchers stage rally in Hollywood to show support for law enforcement officers

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.