Late-season rains mask looming fire danger as lush plants turn dry and explosive

Giant green stems with budding yellow flowers greeted hikers along a narrow path beneath the soaring Santa Monica Mountains on a recent drizzly day.

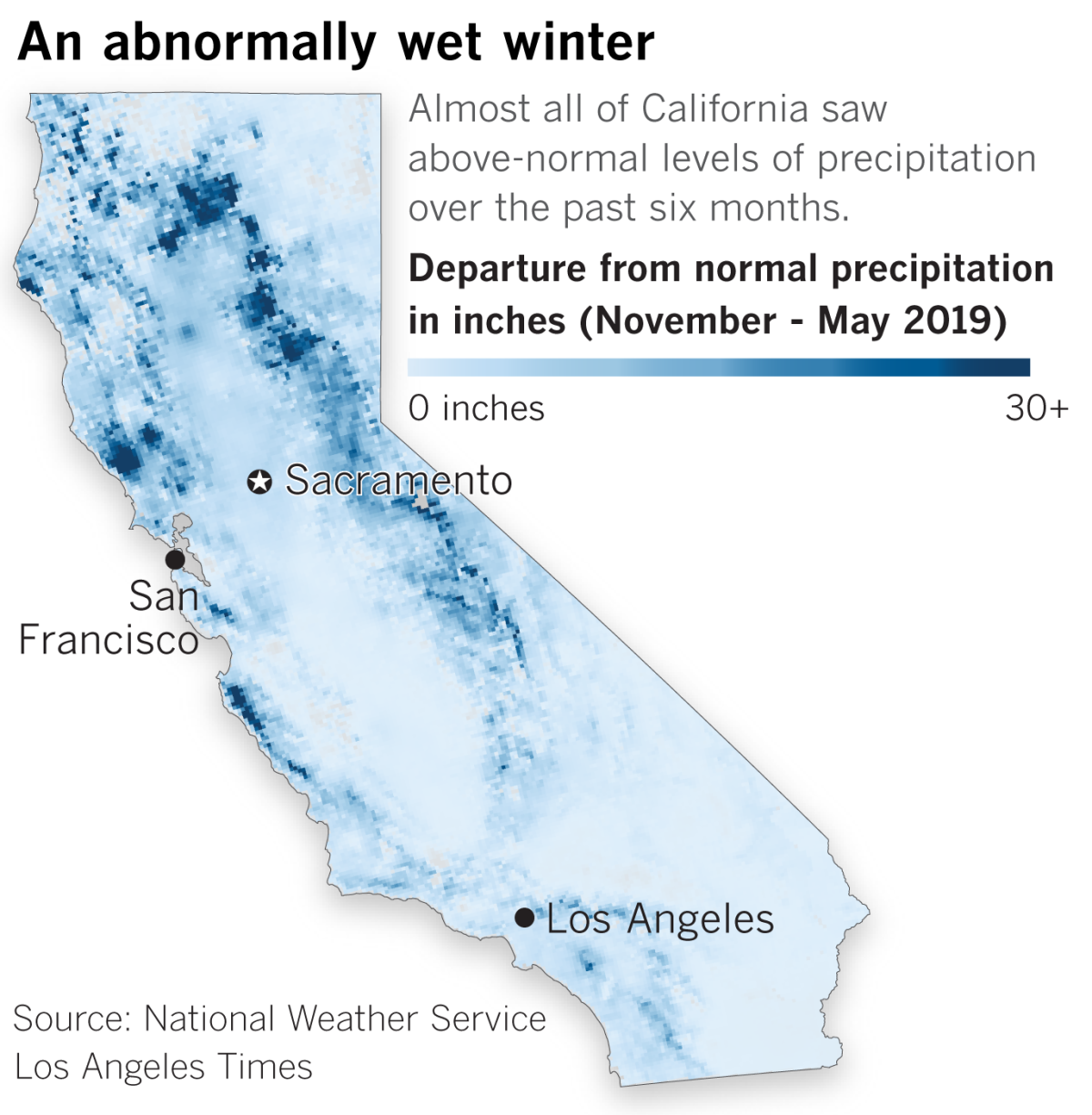

This is where, just seven months ago, the worst fire in Los Angeles County history swept through, destroying more than 1,000 homes and blackening miles of hillsides and canyon. But thanks to one of the wettest seasons in years, rains have transformed the fire zone back to life with great speed.

And all those flowering black mustard plants point to a looming disaster once the rains finally end and Southern California shifts to its dry, hot, windy summer and fall.

California’s wet winter is set to extend well into May thanks to some new storms, but fire experts and climatologists said the extra moisture is likely to worsen the fire outlook because it will allow brush to grow even more.

Mike Mohler, a spokesman for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, estimates the this latest rainstorm will create at least the third layer of dried, dead grass that will blanket the state through the summer and into the fall.

RELATED: What is your neighborhood’s fire risk?

“It will probably cure and die in the next seven to 10 days,” he said. “Now we have all that fuel bed again.”

Wet springs have historically been linked to more severe fires later in the year across much of the state, as the added moisture allows for increased vegetation growth, experts say.

In areas hit repeatedly by fires, non-native plants — like mustard — can grow faster than native species. Those plants eventually dry out during warm summer months and become fuel for wildfires. There are also still tens of millions of drought- and bark beetle-ravaged dead trees standing in the Sierra, ready to act as kindling for the next big blaze.

“The good news is we need the water, but the bad news is it’s building the fuel load for what has always been our fire season,” said Bill Patzert, a local weather expert and former climatologist with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

A look at recent fire activity in the Central Valley and inland desert provide a sense of what the future could hold for the fire season across much of the state, Mohler said.

Earlier this month, Kern County firefighters scrambled to extinguish a wind-driven grass fire that ran across 2,500 acres in a day. In Thermal, a vegetation fire that broke out Saturday night grew amid 50 mph winds to more than 100 acres and injured a firefighter in the process.

“That’s almost a precursor to what we can see statewide,” Mohler warned.

The placement of the jet stream, a high-altitude river of air running form the Pacific across the United States, is a key factor playing into the state’s unusually wet and snowy May. The meandering jet stream has hammered California with a series of storms out of the South Pacific through winter and into the spring.

The atmospheric rivers that have made up much of this winter’s rain has bolstered the snowpack — a key source of the state’s water supply — filled reservoirs and streams, and lifted California out of drought conditions for the first time in nearly a decade. However, the storms typically move too fast and dump too much water at one time to have the kinds of long-lasting benefits California’s parched soil needs.

Experts say the widespread rainfall will likely delay the start of the state’s grass fire season, which typically begins in May or early June, by at least a few weeks.

Also, most of California’s native grasses have gone dormant for the season and won’t sprout for the latest storms, said Robert Krohn, a U.S. Forest Service meteorologist in Riverside County.

“We’re just stalling for time going into the drier part of the year,” Krohn said.

Indeed, a report published earlier this month by the National Interagency Fire Center found that while the fire season was off to a slow start, California can still expect “above normal” potential for large wildfires this summer as heavy crops of grasses sprouted by the wet winter dry out.

Below-normal wildland fire potential is expected in the southern Sierra in June and July thanks to the heavy snowpack slowly melting. But heavy grass loads and a high number of dead trees in the Sierra foothills will lead to above-normal fire potential in many lower-elevation valleys.

Southern California experienced the typical transition from cool, rainy weather to a warmer, drier pattern in April, and most storms that hit the West Coast were too far north or weren’t wet enough to provide widespread rain, according to the National Interagency Fire Center’s outlook report.

The study said cooler temperatures could help Southern California during its fire season.

But by June, the mountains and forests around the Bay Area as well as the Sacramento Valley and nearby foothills are projected to have above-normal fire potential. The areas with above-normal fire potential are expected to expand north to the Oregon border in August. The report also noted that there is a large number of dead and downed trees and plants in the northern Sacramento Valley because of a heavy snowstorm in February that caused extensive damage. That will increase the potential of significant wildfires.

In 2017, heavy rains were followed by devastating fires that hit wine country. Krohn said that the conditions there are different from what Southern California experienced this year.

In 2017, Southern California received the bulk of its rain in the late fall and early winter before the spigot was completely shut off by March, essentially “flash-drying” the landscape, Krohn said.

This year, the storms are stretched out, giving communities time to prepare. Once the storms are gone the area is poised to see some grass fire activity within two or three weeks after the final rainfall.

“Take advantage,” Mohler said. “Take this window — don’t get a false sense of security — to clear your property while moistures are up. Work on evacuation plans. Almost take this as a call to action. This doesn’t happen every often.”

Officials are particularly concerned about the yellow bloom of the invasive plant Brassica nigra, better known as black mustard, that have covered the hillsides throughout the Santa Monica Mountains and much of the West.

The tough plant germinates early in winter before native plants have taken hold, shoots up more than 6 feet tall, hogs the sunlight with its thick stalks and lays down a deep system of roots that beats out native plants for water. The weeds tend to dry up by July or August, and along with invasive European grasses they serve as kindling during Southern California’s long wildfire season

In the Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in Tulare County, prescribed burns that typically happen in the spring may have to wait until the summer, park spokesman Mike Theune said. That could include one in the area near the General Sherman tree set for a few weeks from now, he said.

Even those burns will only happen if conditions are right and firefighters aren’t busy battling a blaze elsewhere.

“What our concern becomes is, eventually the grasses and other vegetation will dry out. We don’t want to let our guard down. We want to remain vigilant because at some point a wildfire will happen,” he said.

“Just because it’s raining now — four months from now, six months from now — no one is going to remember when everything is dried or cured.”

Times staff writers Richard Winton, Javier Panzar and Ralph Vartabedian contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.