UC is handing out generous pensions, and students are paying the price with higher tuition

- Share via

As parents and students start writing checks for the first in-state tuition hike in seven years at the University of California, they hope the extra money will buy a better education.

But a big chunk of that new money — perhaps tens of millions of dollars — will go to pay for the faculty’s increasingly generous retirements.

Last year, more than 5,400 UC retirees received pensions over $100,000. Someone without a pension would need savings between $2 million and $3 million to guarantee a similar income in retirement.

The number of UC retirees collecting six-figure pensions has increased 60% since 2012, a Times analysis of university data shows. Nearly three dozen received pensions in excess of $300,000 last year, four times as many as in 2012. Among those joining the top echelon was former UC President Mark Yudof, who worked at the university for only seven years — including one year on paid sabbatical and another in which he taught one class per semester.

The average UC pension for people who retired after 30 years is $88,000, the data show.

The soaring outlays, generous salaries and the UC’s failure to contribute to the pension fund for two decades have left the retirement system deep in the red. Last year, there was a $15-billion gap between the amount on hand and the amount it owes to current and future retirees, according to the university’s most recent annual valuation.

“I think this year’s higher tuition is just the beginning of bailouts by students and their parents,” said Lawrence McQuillan, author of California Dreaming: Lessons on How to Resolve America’s Public Pension Crisis. “The students had nothing to do with creating this, but they are going to be the piggy bank to solve the problem in the long term.”

At a UC Board of Regents meeting this month, university officials began discussing next year’s budget and broached the possibility of another tuition increase. Pensions and retiree healthcare topped their list of growing expenses, but it’s unclear whether regents would approve another hike.

Public pension funds are in crisis across the country, and particularly in California. The underlying cause is essentially the same everywhere. For decades, government agencies and public employees consistently failed to contribute enough money to their retirement funds, relying instead on overly optimistic estimates of how much investments would grow.

UC’s pension problem, while not unique, is distinctly self-inflicted. In 1990, administrators there stopped making contributions for 20 years, even as their investments foundered, leaving a jaw-dropping bill for the next generation — which has now arrived.

After setting aside about a third of the new money for financial aid, university officials expect this year’s increased tuition and fees for in-state students to generate an extra $57 million for the so-called core fund, which pays for basics like professors’ salaries and keeping the lights on in the classrooms. But they also expect to pay an extra $26 million from the fund for pensions and retiree health costs, according to the university’s most recent budget report.

UC spokeswoman Dianne Klein said it’s impossible to say precisely how much of the tuition increase will go toward retirement costs because the university pools revenue from a variety of sources, including out-of-state tuition and taxpayer money from the state general fund, to cover expenses.

The steep rise in six-figure pension payments over the last five years was driven by a wave of retiring baby boomers with long tenures at high salaries, Klein said. “UC, as you know, has an aging workforce.”

University officials have attempted to control costs by increasing the retirement age and capping pensions for new hires, but those are long-term fixes that won’t yield significant savings for decades. And the current budget promises $144 million in raises for faculty and staff, a move that will send future pension payments even higher.

The top 10 pension recipients in 2016 include nine scholars and scientists who spent decades at the university: doctors who taught at the medical schools and treated patients at the teaching hospitals, a Nobel Prize-winning cancer researcher and a physicist who oversaw America’s nuclear weapons stockpile.

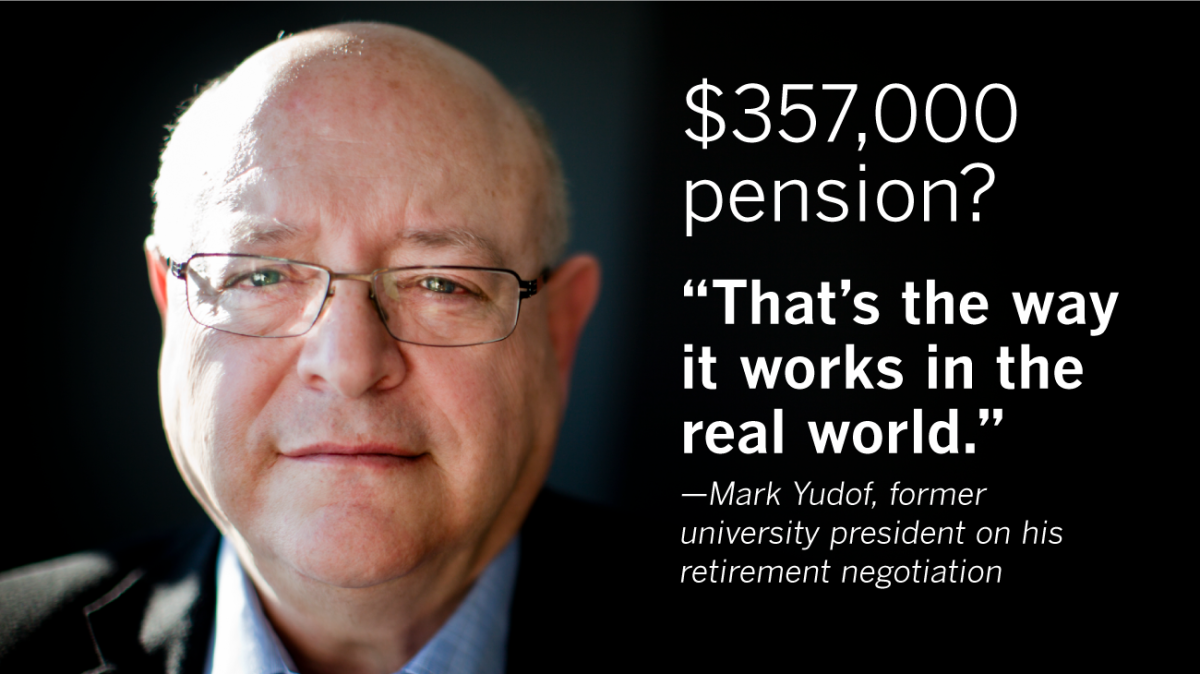

The exception is Yudof, who receives a $357,000 pension after working only seven years.

Under the standard formula — 2.5% of the highest salary times the number of years worked — Yudof’s pension would be just over $45,000 per year, according to data provided by the university.

But Yudof negotiated a separate, more lucrative retirement deal for himself when he left his job as chancellor of the University of Texas to become UC president in 2008.

“That’s the way it works in the real world,” Yudof said in a recent interview with The Times.

The deal guaranteed him a $30,000 pension if he lasted a year. Two years would get him $60,000. It went up in similar increments until the seventh year, when it topped out at $350,000.

Yudof stepped down as president after five years, citing health reasons. Under the terms of his deal, his pension would have been $230,000. But he didn’t immediately leave the university payroll.

First, he collected his $546,000 president’s salary during a paid “sabbatical year” offered to former senior administrators so they can prepare to go back to teaching. The next year he continued to collect his salary while teaching one class per semester, bringing his tenure to seven years and securing the maximum $350,000 pension.

In 2016 he got the standard 2% cost-of-living raise, resulting in his $357,000 pension.

Asked if he was worth all the money, Yudof said it would be more appropriate to ask the members of the university’s Board of Regents, who agreed to the deal.

Richard C. Blum, who was chairman of the board in 2008, did not respond to requests for comment.

Six of the top 10 pensions recipients last year — each of whom got more than $330,000 — were doctors who taught at the medical schools or treated patients at the teaching hospitals.

For decades, university officials have argued that the generous pension plan is essential to compete with other top schools, especially private ones that offer higher salaries.

Rival medical schools in California, including Stanford and USC, do not provide doctors guaranteed, lifetime pensions. Instead, they offer defined contribution plans in which the employer and employee each pays into the employee’s personal retirement account. When the worker retires, he or she gets the money and the employer is off the hook — no lifetime of continuing payments.

The vast majority of doctors in the U.S. who don’t work for public universities are offered such plans instead of pensions, as are the vast majority of other professionals working in private industry.

Three physician recruiters told The Times that they thought persuading top doctors to work at UC would be easy, given the prestige of the institution and the fact that the hospitals are located in some of the nation’s most desirable places to live.

“I think I could sell it against a higher-paying job in the private sector, even without a guaranteed pension,” said Vince Zizzo, president of Fidelis Partners, a national search firm based in Dallas. Working for a university “is a protected world of guaranteed this and guaranteed that,” Zizzo said. In private practice, doctors are paid based on the number of patients they see and how much they bill. “It’s a much harder life; you eat what you kill.”

Most of UC’s top pension recipients did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Two interviewed by The Times said they were grateful for the pensions, but the retirement plan played no role in their decision to take jobs at the university early in their careers.

Nosratola Vaziri, a former kidney and hypertension specialist at UC Irvine’s medical school, collected a $360,000 pension last year. He went to work at UCI after finishing a fellowship at UCLA in 1974 and stayed for the next 37 years, contributing to more than 500 scientific articles. Despite offers from other institutions, he never left because he loved the work, Vaziri said.

“Neither salary nor pension were the reason for my choice,” Vaziri said.

Radiologist Lawrence Bassett spent 41 years working at UC hospitals after finishing his residency at UCLA. He specialized in the emerging field of breast imaging and said UC was a great place to benefit from leading research. Asked whether the pension had been a factor in his decision to take the job initially, or stay over the years, Bassett said, “No, honestly it wasn’t.” Bassett’s pension was $347,000 last year.

McQuillan, the author and Senior Fellow at the Independent Institute, a nonpartisan think-tank in Oakland, said it would be simpler, more transparent and ultimately cheaper for UC hospitals and medical schools to compete with other institutions by paying higher salaries.

Pensions involve a guess about how much the employer will have to invest today to pay a retiree a guaranteed amount later. It’s common for public officials to guess low, saving money in the short term, and leaving their successors to figure out how to make up any shortfall.

That’s what has been happening at UC for decades, McQuillan said. “At least with a big salary, there isn’t this ticking time bomb that’s going to explode 30 years down the road.”

Like most public employee pensions — they’re rare in the private sector these days due to the cost — UC’s is funded through regular paycheck contributions from employers and employees. The money is invested in stocks, bonds and real estate around the world with the hope that it will grow enough over time to cover the guaranteed payments in retirement.

As is often the case, the UC pension fund’s financial trouble didn’t begin when there was too little money; it began when there was too much.

In 1990, after years of strong investment returns, university officials determined the fund had accumulated more than it would owe retirees into the foreseeable future. So they took what was supposed to be a temporary “holiday” from making contributions to the fund. They let employees do the same.

The policy was popular and difficult to overturn even as the fund started slipping into the red.

By the time contributions were reinstated in 2010, the fund had fallen billions of dollars behind.

Since then, university administrators have been scrambling to catch up, borrowing and transferring $4 billion from other university accounts to plow into the pension fund. They also raised the minimum retirement age from 50 to 55.

In 2015, Gov. Jerry Brown offered a $436-million gift of state taxpayer funds in exchange for an agreement from UC President Janet Napolitano to cap the amount of salary that can be used to calculate a pension at $117,000 — a move that will save money decades from now, but does little in the short term.

The deal also required Napolitano to offer new employees the choice of a defined contribution plan.

Despite all these efforts, UC’s pension hole hasn’t shrunk since 2010; it has grown by billions, according to the university’s most recent valuation. That’s because the return on investments has not kept pace with the growth in staff, salaries and departing employees’ pension payments. This year’s stock market gains will help but have not yet been included in the published valuations.

As the university struggles to deal with the problem, Napolitano’s office has become a jealous guardian of pension information.

In December, the nonprofit California Policy Center sent a public records request to UC for an update of a 2014 spreadsheet listing pension payments to the university’s retirees. A school administrator responded with an email saying UC had provided the previous spreadsheet as a “courtesy” and was no longer willing to do so.

When the nonprofit pressed — the information is indisputably public under the law, and other California government agencies routinely provide pension data without delay — the administrator sent an email claiming that the employee who created the 2014 spreadsheet had since retired and nobody could find the query he had used to extract the information from a larger database.

“They lost the computer program? That’s not my problem,” said Craig P. Alexander, a Dana Point attorney representing the nonprofit. The university finally turned the pension data over in May, but only after the Alexander threatened to sue.

Napolitano’s staff also initially refused when The Times requested the pension information in February. It took until June for them to provide usable data — which showed the dramatic rise in six-figure pension payments and revealed for the first time the full amount of Yudof’s pension.

Follow on Twitter at @JackDolanLAT

ALSO

Deal for new city at Newhall Ranch fuels development boom transforming northern L.A. County

Death toll from West Nile climbs to 7 in L.A. County, officials say

Busy U.S.-Mexico border crossing reopens ahead of schedule

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.