XXXTentacion, controversial rapper who broke out amid legal troubles, dead at 20

- Share via

XXXTentacion’s rise was as quick as it was controversial.

In the past year the rapper’s homespun brand of hip-hop pushed him to the front of a pack of young emcees looking to disrupt the genre with a new sound.

Yet trouble and controversy were never far from XXXTentacion, who was killed in South Florida on Monday afternoon just three months after hitting the top of the charts with his latest album.

The Broward County Sheriff’s Office confirmed the rapper, born Jahseh Onfroy, was shot outside of Riva Motorsports in Pompano Beach, Fla., by an unidentified gunman who fled the scene after an apparent robbery. Onfroy was rushed to a local hospital, where he was later pronounced dead. He was 20.

“Everyone at Caroline is shocked to learn of the tragic death of Jahseh Onfroy, professionally known as XXXTentacion,” said a statement from the label that distributed his music. “We extend our heartfelt condolences to his family and loved ones.”

This time last year, Onfroy’s burgeoning career was reaching a new peak.

Although the Florida native had already amassed a fervent cult following and the attention of major labels over his blistering, lo-fi anthem “Look at Me” — it hit the top 40 of the U.S. pop charts due largely to millions of streams from Spotify and SoundCloud — a spat with superstar Drake, who was accused of co-opting its rhythm, put the song and the rapper on mainstream radars.

Soon, XXXTentacion (that’s “X -X -X -Ten-Tah-See-Ohn “) found himself as the face of a movement of SoundCloud rappers upending hip-hop tradition.

But as he was becoming a name, Onfroy was sitting behind bars in a Broward County jail, charged with multiple felonies for allegedly beating and strangling his then-pregnant ex-girlfriend in 2016. Onfroy was also accused of false imprisonment and witness tampering and faced up to 30 years in prison. He had pleaded not guilty to the crimes.

“I looked at him, and I’m seeing someone who literally got dealt a bad hand in life,” Onfroy’s manager, Solomon Sobande, told The Times of the first time he met the artist, the two separated by a thick glass partition.

“Knowing he had all this potential, I was sad for the kid,” Sobande continued. “He’s got his own issues, but it’s safe to say he didn’t get the fairest hand.”

Onfroy’s ascent in music was fierce. He collaborated with Diplo and Noah Cyrus and sold out shows across the country, with fans eager to get close to the enigmatic performer who rarely gave interviews. Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar and A$AP Rocky were among his fans, and his debut album, “17,” reached No. 2 on the Billboard 200.

His music had amassed a billion streams on Spotify; he was selected for XXL’s highly coveted Freshman List last year, following the likes of Lamar, J. Cole and Chance the Rapper; and Onfroy scored a distribution agreement to the tune of a reported $6 million between his own imprint and Caroline Records (part of Capitol Music Group).

But his soaring success was a case study in separating art from artist as listeners, critics and some of his fans grappled with the real-life troubles he sang about.

Born in Plantation, Fla., with “a melting pot,” as he’s put it, “of Jamaican, Syrian and Italian” heritage, Onfroy had a rough upbringing.

His mother struggled to care for him and as a child he was shuttled around to various caregivers. “He was always living with other people … for years,” said half-sister Ariana Onfroy, in a video she posted online.

He claims to have fended off a man attacking his mom by biting and slicing him with a glass shard as a 6-year-old. He was expelled from middle school for fighting and tossed out of several more schools before he landed in juvenile detention over a gun charge.

“When I was younger, it was hard on my mom, because she didn’t have my father around or her mother around to even remotely help her,” the rapper said in press notes for “17.” “When she would sing, I saw how her mood changed. During work, she used to leave me with people to take care of me. I felt alone, so I would use records as my company. I’ve found that music can silence the brain altogether and alter your thought process to where you reach a meditative state. I really connected with artists that displayed real emotion.”

It didn’t take long for Onfroy to turn to music himself as an emotional outlet. He joined his school choir and discovered genres like nu-metal, rock and rap by listening to Papa Roach, Eminem, Nirvana and the Fray.

By the time he was 16, he was recording and posting his grungy confessionals to SoundCloud. “Music saved me as an individual because I was literally haunted by myself,” he said. “As a person, I was lost. [Music] gave me a purpose. Within that purpose, I became able to display my pain for others.”

He channeled the pain and trauma he experienced in his life into his music, tackling heavy subjects like his struggles with mental illness, abuse, suicide and incarceration (he was charged with committing home invasion, robbery and aggravated battery with a firearm in 2015, according to court records).

“If death is what it seems, why is it so vividly portrayed within my dreams,” he wonders on “Vice City,” an early SoundCloud offering. On “17,” a track is dedicated to a 16-year-old girl who committed suicide during a trip to model for him. To make a point about racism, he showed a white child being hanged in a music video.

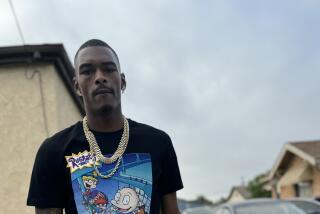

An outlaw attitude paired with a wild, stark appearance — the words “Numb” and “Alone” were tattooed on his face, along with a broken heart and other scrawlings, and his dreadlocks were evenly split between blond and black — fueled his hard image. In fact, his label famously used his mug shot as publicity stills, a move that was part gimmick and part necessity.

Despite his mounting troubles, Onfroy’s career showed no signs of slowing down.

Though he was briefly jailed last year after being slapped with 15 felony counts of witness tampering and harassment in connection with the 2016 domestic violence case, he resumed his career after being on house arrest.

In March he released what would be his last album, “?” It went straight to No. 1, a first for the rapper, due largely in part to his massive following on streaming services — which came under fire recently when he was one of two controversial acts targeted by Spotify’s Hate Content and Hateful Conduct public policy, a poorly received initiative that saw him and R. Kelly pulled from playlists and algorithmic recommendations. The policy was quickly reversed.

On a recent dispatch to fans via Instagram, Onfroy was thinking about how he wanted to be remembered. In a chilling bit of irony, he could be seen waxing poetically about his death while behind the wheel, the place he was later targeted by assailants.

“Worst thing comes to worst, I … die a tragic death or some … and I’m not able to see out my dreams, I at least want to know that the kids perceived my message and were able to make something of themselves and able to take my message and use it and turn it into something positive, and at least have a good life,” he said. “If I’m gonna die or ever be a sacrifice, I want to make sure that my life made at least 5 million kids happy.”

For more music news follow me on Twitter:@GerrickKennedy

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.