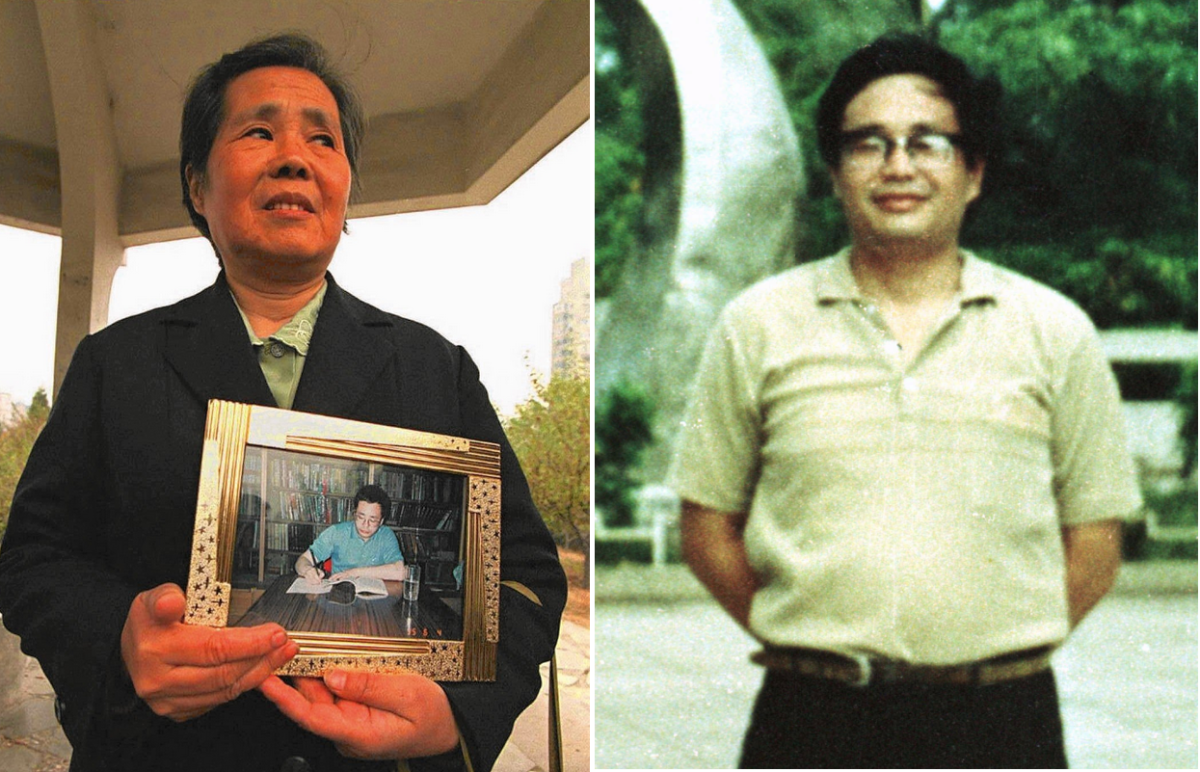

Chen Ziming dies at 62; activist jailed after Tiananmen protests

- Share via

Twenty-five years after Chinese government tanks crushed the massive pro-democracy uprising in Tiananmen Square, an activist branded as one of the “black hands” behind the 1989 event has died in his Beijing home.

Chen Ziming’s death Tuesday was caused by pancreatic cancer, according to Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post. He was 62.

Chen, who was convicted of sedition in 1991, spent about 13 years behind bars or confined to his apartment. In response to economic pressure from the United States, Chinese authorities released him in 1994 but imprisoned him again in 1995 after he staged a 24-hour hunger strike commemorating Tiananmen. Suffering from testicular cancer and other illnesses, he was allowed to go home, under house arrest, in 1996.

Even after his sentence ended, the scholarly but impassioned Chen was under constant surveillance, he told interviewers. He published political commentaries under 30 pseudonyms. With permission from various government agencies, he started a website called “Reform and Construction,” but it was shut down, he said, for no apparent reason.

“They just pull the plug on you because they can,” he told Radio Free Asia in 2006.

In the years before the Tiananmen Square massacre, Chen, a biochemist by training, was one of China’s most prominent social scientists. With his longtime colleague Wang Juntao, he founded an influential think tank, ran a dissident magazine called Beijing Spring, published the reform-minded Economics Weekly, and started China’s first independent political surveys.

“No project worried the authorities more,” wrote George Black and Robin Munro in their 1993 history, “Black Hands of Beijing.” Funding came partly from U.S. organizations like the Ford Foundation and the National Science Foundation. A finding that 72% of Chinese believed democracy to be the best form of government “provided explosive evidence of the country’s frustrated mood,” the authors wrote.

Although Chen was a political moderate, authorities saw him as a threat, said Yang Jianli, a Chinese dissident who spent five years in prison on spying charges.

“We have a lot of intellectuals and some good organizers but rarely are they combined,” Yang told The Times this week from a human rights conference in Oslo, Norway. “Chen was among the very few who could think, devise strategy and organize.”

Yang, who heads a Washington, D.C., group called Initiatives for China, said Chen exerted “a tremendous influence” among intellectuals.

However, he had less sway over the legions of protesters camped out in Tiananmen Square. Asked to intervene by government officials and pressed by student leaders for counsel on tactics, Chen and his colleagues at first tried to mediate. When the government imposed martial law, they urged the protesters to withdraw.

Hundreds of them — thousands, according to some estimates — were killed on the square and the streets leading to it when the tanks rolled in on June 4, 1989.

At Chen’s trial for “counter-revolutionary incitement,” he denied charges that he and Wang Juntao were the demonstration’s masterminds — or, in the parlance of prosecutors, its “black hands.”

“We opposed chaos and rebellion, we opposed the new attitudes … the prattling about ‘without destruction there can be no construction,’” he told the court. “In my opinion, the movement was an emotionally sincere, well-intentioned, pigheaded, mismanaged historical incident with a tragic ending.”

Its “solemn sense of beauty,” he said, “will always merit the people’s admiration.”

While China has undergone dramatic economic and social changes since Tiananmen, the government still suppresses any commemoration of the event. Its 25th anniversary went unmentioned in state-run media.

Born in 1952, Chen grew up in privilege and attended elite schools in Beijing before he was assigned to work in Inner Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution. For six years, he inoculated peasants against infectious diseases, worked in the fields, and, at night, read Marx and Lenin in his yurt.

A rising star in the Communist Party, he was admitted to the University of Science and Technology but was arrested in 1975 for “counter-revolutionary offenses.” He had written his friend a letter criticizing national leaders.

The following year, Chen had to report to a labor camp but before he did so, he took part in a massive Tiananmen demonstration against the “Gang of Four” running the country. When he had worked his way to the protest posters at the front of the crowd, someone tapped him on the shoulder and asked him to read aloud. Chen’s oration was passed back through the endless ranks.

“That hand on my shoulder made a wave 10,000 feet high in my brain,” he later wrote.

When the Gang of Four fell in October 1976, Chen resumed his studies. He and his wife Wang Zhihong organized a chain of correspondence colleges before he co-founded the Beijing Social and Economic Sciences Research Institute.

As the explosive 1989 Tiananmen protest started, Chen and Wang Juntao agonized over how deeply to involve themselves.

“The democracy movement had turned into a tidal wave that threatened to wash away all their … patient years of work to create the independent intelligentsia that China lacked,” Black and Munro wrote in “The Black Hands of Beijing.”

“On the other hand, if they chose to stand aloof, could they ever look in the mirror again?”

On the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen in June, Chen called for the government to reverse the verdicts against him and others as “an important, symbolic step.”

He was allowed to come to the U.S. earlier this year for medical treatment in Boston.

Chen is survived by his wife.

Asked once why he had not, like Wang Juntao and other dissidents, gone into exile, he was incredulous.

“I am Chinese,” Chen said. “Why should I live in another country?”

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.