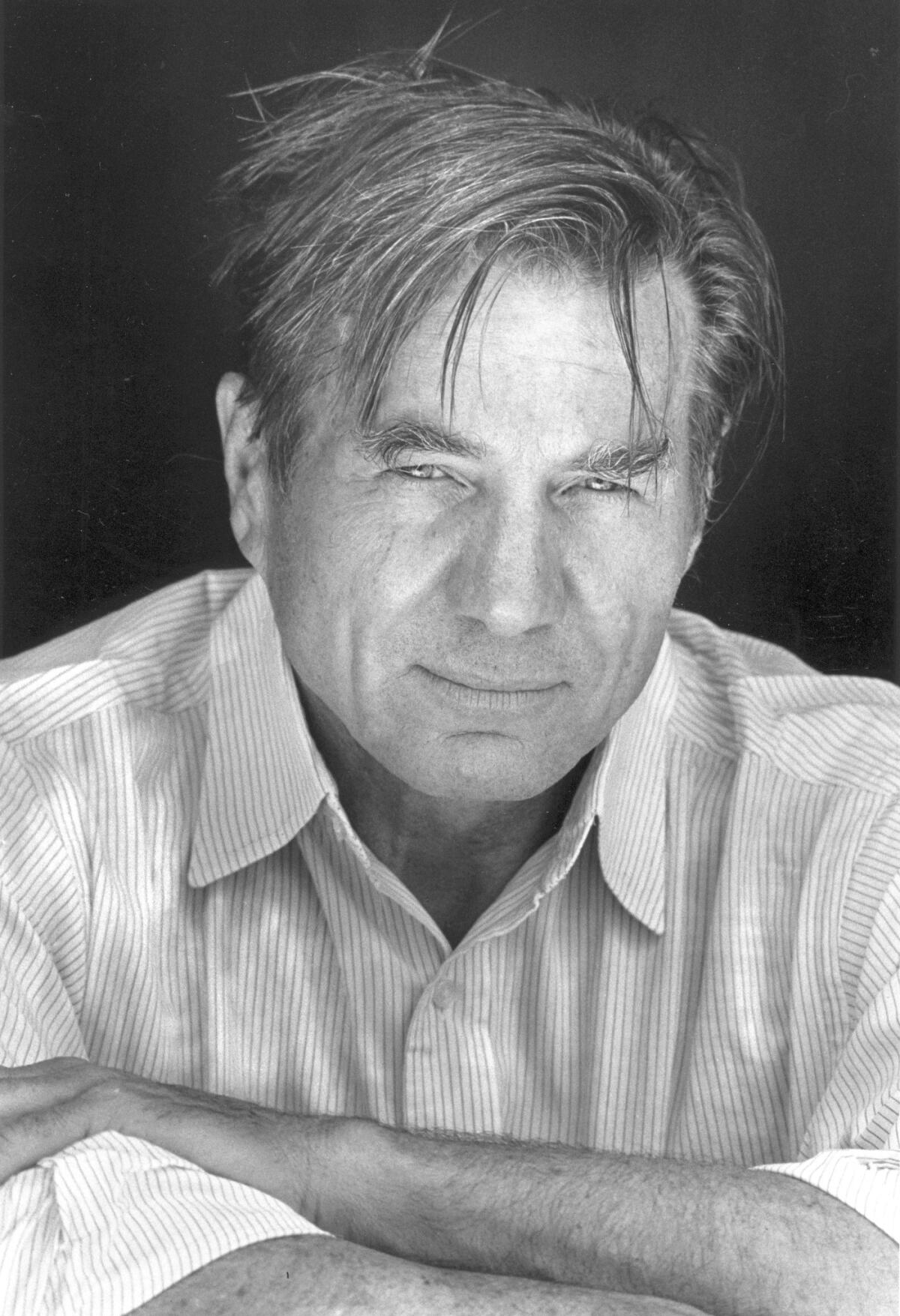

Poet Galway Kinnell, winner of Pulitzer Prize, dies at 87

Galway Kinnell, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who opened up American verse in the 1960s and beyond through his forceful, spiritual takes on the outsiders and underside of contemporary life, has died. He was 87.

Kinnell died of leukemia Tuesday at his home in Sheffield, Vt., said his wife, Bobbie Bristol.

Among the most celebrated poets of his time, he won the Pulitzer and National Book Award for the 1982 release “Selected Poems” and later received a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship. In 1989, he was named Vermont’s poet laureate, and the Academy of American Poets gave him the 2010 Wallace Stevens Award for lifetime achievement. His other books include “Body Rags,” “Mortal Acts, Mortal Words,” “The Past” and his final book of poetry, “Strong Is Your Hold,” released in 2006.

Kinnell’s style blended the physical and the philosophical, not shying from the most tactile and jarring details of humans and nature, exploring their greater dimensions. He once told The Times that his intention was to “dwell on the ugly as fully, as far and as long” as he “could stomach it.”

In one of his most famous poems, “The Bear,” he imagines a hunter who consumes animal blood and excrement and comes to identify with his prey, wondering “what, anyway, was that sticky infusion, that rank flavor of blood, that poetry, by which I lived?”

The youngest of four children, Kinnell was born Feb. 1, 1927, in Providence, R.I., and raised in Pawtucket. He was influenced in childhood by Emily Dickinson and Edgar Allan Poe among others.

“I was a very silent child, almost mute,” Kinnell said during a 1985 appearance at Chapman College in Orange. “I think everybody was too busy to talk to me. I developed a big sense of isolation from others.... Gradually I felt that if I was ever going to have a happy life, it was going to have to do with poetry.”

He graduated from Princeton University, served in the Navy in World War II, traveled widely, opposed the Vietnam War and served as a field worker for the Congress of Racial Equality civil rights organization. Like his friend and contemporary W.S. Merwin, he began weaving in the events of the time into his poetry.

In “Vapor Trail Reflected in the Frog Pond,” from the 1968 collection “Body Rags,” he invokes the chanting style of Walt Whitman to condemn American violence:

And I hear,

coming over the hills, America singing,

her varied carols I hear:

crack of deputies’ rifles practicing their aim on stray dogs at night,

sput of cattleprod,

TV going on about the smells of the human body,

curses of the soldier as he poisons, burns, grinds, and stabs

the rice of the world,

with open mouth, crying strong, hysterical curses.

University of Vermont poet and English professor Major Jackson, who read one of Kinnell’s poems during an August ceremony at the Vermont Statehouse honoring Kinnell, called him one of “the great quintessential poets of his generation.”

“In my mind he comes behind that other great New England poet Robert Frost in his ability to write about not only the landscape of New England, but also its people,” said Jackson. “Without any great effort it was almost as if the people and the land were one, and he acknowledged what I like to call a romantic consciousness.”

Kinnell taught at numerous schools, including Reed College and New York University, and for several years was a visiting poet at Sarah Lawrence College. From 2001 to 2007, he served as chancellor of the poets academy.

Besides his wife, he is survived by two children from a previous marriage and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.