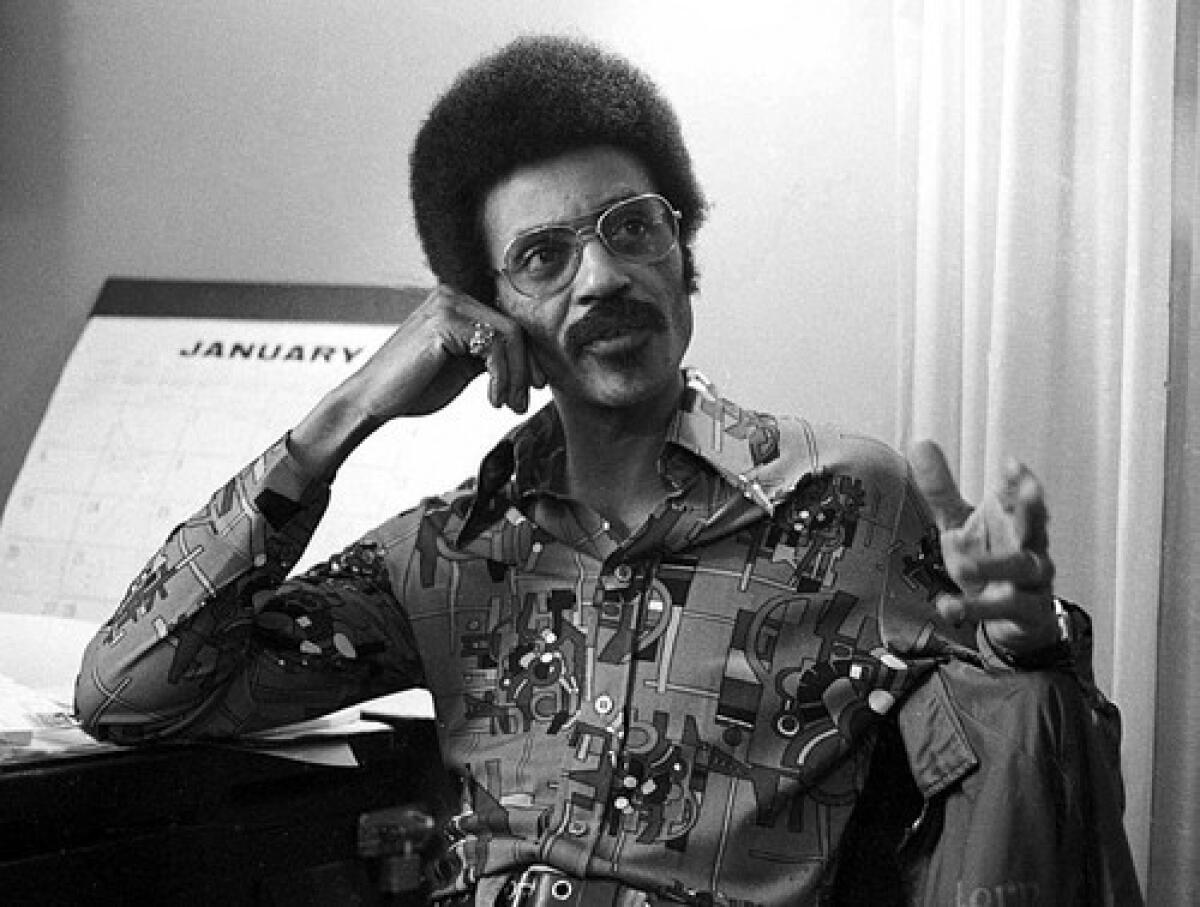

Warren Kimbro dies at 74; former Black Panther who led Project MORE

- Share via

Warren Kimbro, a former Black Panther whose 1969 murder of a suspected informant brought on the unsuccessful prosecution of party co-founder Bobby Seale in one of an unruly era’s most raucous episodes, died Tuesday in New Haven, Conn., where he rebuilt his life as head of a rehabilitation program for ex-offenders. He was 74.

The cause was believed to be a heart attack, said Douglas Rae, a Yale School of Management professor who knew Kimbro for two decades and co-authored a book about him.

On May 20, 1969, Kimbro fatally shot Alex Rackley, a 19-year-old Black Panther member who party members thought was an FBI informant. Prosecutors said the killing was ordered by Seale, whose 1970 trial in New Haven became a cause célèbre for the radical left.

Seale was freed after the jury failed to reach a verdict, but Kimbro was convicted of second-degree murder and went to prison for nearly five years. He rehabilitated himself there, earned a master’s degree in education from Harvard and for 25 years led Project MORE, a nonprofit agency devoted to helping ex-cons reenter society.

“The most important part of Warren Kimbro’s life began when he left prison,” Rae, a longtime Project MORE board member, said last week. “He was a remarkable leader who set a tone and a standard in the New Haven community that hundreds of us learned to respect.”

One of eight children in a strict Roman Catholic family, Kimbro was born in New Haven on April 29, 1934. His mother was a Republican ward chairwoman in New Haven, while his father worked for a steel plant.

A high school dropout, Kimbro served in Korea during five years in the Air Force. After completing his military duty, he returned to New Haven, which by the mid-1960s was flush with money from President Johnson’s Great Society programs, and became a community organizer for a local antipoverty effort.

But he quickly grew disillusioned with the program and thought the government was more interested in “controlling rather than empowering poor people,” said Paul Bass, a New Haven journalist who co-wrote with Rae “Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, and the Redemption of a Killer” (2006).

In 1969 Kimbro joined the Black Panther Party, founded three years earlier in Oakland by Seale and Huey Newton with a sweeping agenda to empower blacks by pressing for decent housing and jobs, courses in African American history, amnesty for black prisoners and an end to police brutality. They also preached self-defense and armed their members, which led FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to investigate the group. Fears of FBI surveillance and infiltration pervaded the Panther ranks.

Kimbro’s apartment became the headquarters for New Haven’s Panther chapter. It was there that Rackley was interrogated and tortured for three days before a brash Panther leader named George Sams ordered Kimbro and another party member to take him away.

Afraid that he might be the next one purged, Kimbro cooperated. He and a fellow Panther, Lonnie McLucas, drove to a swamp outside New Haven and, at Sams’ order, shot and killed Rackley, who was never proved to be an FBI plant. His body was found by fishermen the next day.

Nine Panthers were eventually put on trial for the killing, with Seale’s case drawing the most attention. Thousands of protesters -- including Tom Hayden, Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Dr. Benjamin Spock and other luminaries of the left -- descended on New Haven to demand the release of the Panthers and their charismatic leader.

Kimbro confessed to the murder and became a witness for the prosecution. In prison he rediscovered his Christian faith and became a model inmate who counseled fellow prisoners, published a prize-winning prison newspaper and took correspondence courses to earn a college degree. At one point he was running a drug-treatment program outside the prison and returning to his cell at night. His conduct was so exemplary that the state pardoned him after he had served only 4 1/2 years of a life sentence.

After graduate school at Harvard, Kimbro became a student dean at Eastern Connecticut State University. In 1983 he took over Project MORE, which he built into an organization with a $6-million budget and staff of 30 that has helped thousands of ex-offenders redirect their lives.

Rae said Kimbro never made excuses for his involvement in Rackley’s murder. Nor did he let a day pass without remembering that he had killed a man.

He still sought to right society’s wrongs, but as he told a young audience in New Haven several years ago, there are better paths to justice than the one he chose on that May night in 1969.

“I don’t want you to pick up a gun like me,” he said. “I want you to do this revolution by getting into Yale Law School.”

Kimbro is survived by two children, Veronica and Germano; five grandchildren; four great-grandchildren; and a brother.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.