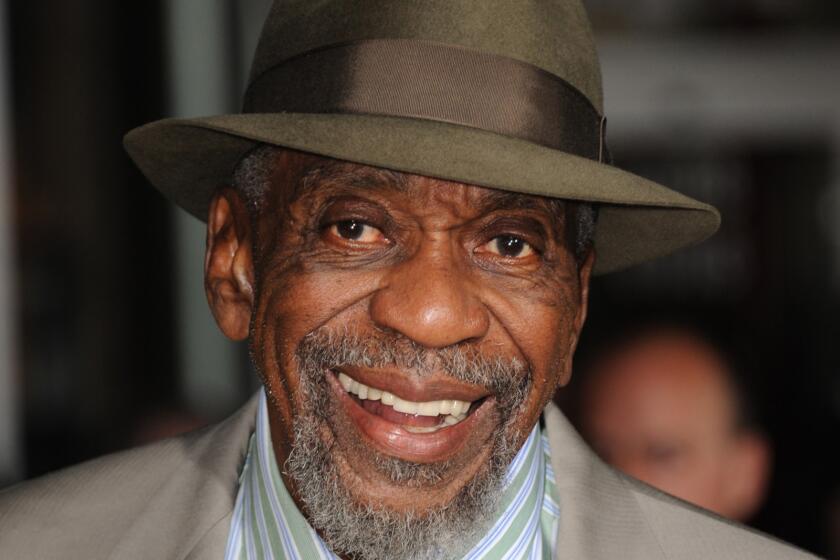

Paul Weyrich, religious conservative and ex-president of Heritage Foundation, dies at 66

Paul Weyrich, the blunt-tongued cultural warrior who helped to engineer the union between the Republican Party and the Christian Right, coined the phrase “moral majority” and was a driving force behind some of the conservative movement’s leading institutions, including the Heritage Foundation, has died. He was 66.

Weyrich died early Thursday at a northern Virginia hospital, according to Lee Edwards, a distinguished fellow at the Washington, D.C.-based foundation who knew Weyrich for 41 years. The cause of death was not immediately known, but Weyrich had faced a number of medical crises over the last dozen years, including diabetes and the amputation of both legs in 2005.

“Paul was a pioneer, a visionary and a tough enforcer of conservative principle,” David A. Keene, chairman of the grass-roots American Conservative Union, said in a statement Thursday. “He had little time for moderates or those who simply gave lip service to the values he held dear. His goal was to recruit conservatives, train them both ideologically and in campaign techniques and send them off to do battle” with liberals.

A committed ideologue, Weyrich battled anyone who did not hew to core conservative beliefs. He frequently criticized Ronald Reagan for ideological insufficiencies on issues such as school prayer and abortion. He famously torpedoed the nomination for defense secretary of former Republican Sen. John Tower by calling attention to Tower’s drinking habits and fondness for women “to whom he is not married.” At a Washington roast in 1991, syndicated columnist Robert Novak teased Weyrich for having alienated so many people that “he gets hate mail from Mother Teresa.”

Weyrich’s role in the Tower fight underscored the nature of his conservatism: It was not just political; it was acutely cultural, concerned with such matters as whether children are taught evolution or creationism in school, or whether homosexuality is portrayed as natural or profane.

“It may not be with bullets and . . . rockets and missiles, but it’s a war nonetheless,” he once said, describing the struggles that began to dominate public discourse in the late 1970s. “It is a war of ideology, it’s a war of ideas, and it’s a war about our way of life. And it has to be fought with the same intensity, I think, and dedication as you would fight a shooting war.”

His intensity was on full display at the weekly luncheons he hosted at the Washington offices of the Free Congress Foundation, where the guest list was dominated by conservative insiders, including many high-ranking members of Congress. He was impatient with speakers who couldn’t tell the group anything new or who veered into pomposity.

“If someone was pontificating, he cut them off. I’ve seen him stop a majority leader in his tracks,” Edwards, a regular at Weyrich’s lunches, recalled Thursday. “Some were a little taken aback. They thought they should be deferred to. Paul didn’t see it that way. He was so committed to the principle and applying those principles.”

His interest in politics began as a child growing up in Racine, Wis., where he was born on Oct. 7, 1942. He was strongly influenced by his father, a German immigrant who shoveled coal for a living but sent his son to school wearing a “Taft for President” button, as in conservative icon Sen. Robert A. Taft of Ohio.

In high school Weyrich was curious about the fact that the Democrats on his mother’s side of the family were as conservative as the Republicans on his father’s side and, as he told the Washington Post several years ago, began to suspect that “historical and regional differences kept natural allies from working together.”

He dropped out of the University of Wisconsin after two years, got married and became a reporter for radio, television and the Milwaukee Sentinel. His survivors include his wife, Joyce, and five children.

Weyrich later became a news director in Denver, where he attracted the attention of Republican Sen. Gordon Allott, who hired Weyrich.

His Colorado connections led him to Joseph Coors, the conservative beer magnate who donated $250,000 to launch the Heritage Foundation in 1973. Weyrich became its first president in 1977. The think tank is widely credited as the intellectual engine of the Reagan Revolution, particularly through a 1981 treatise on limited government called “Mandate for Leadership.”

Weyrich also founded the Free Congress Foundation, the main focus of which, according to its website, is “the Culture War.” It belongs to a network of conservative policy and action groups that he helped to build, including the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Council for National Policy and the Republican Study Committee.

In 1979 Weyrich was in a discussion with the Rev. Jerry Falwell when he remarked that there was a “moral majority” of Americans ready to be called to political action. Falwell “turned to his people and said, ‘That’s the name of our organization,’ ” Weyrich recalled in an interview last year with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The Moral Majority mobilized evangelical Christians into one of the most potent political forces of the Reagan era. Radio and TV producer Norman Lear launched People for the American Way in 1981 to monitor and oppose Weyrich and like-minded threats to liberalism.

Weyrich joined forces with direct-mail fundraiser Richard Viguerie to unseat several incumbent liberal senators, including Frank Church, George McGovern and Birch Bayh, all of whom were defeated in 1980. He described himself as a radical “working to overturn the present power structures in this country.”

By the end of the 1990s, the tide had reversed. Weyrich was so disturbed by the Senate’s acquittal of President Clinton after his impeachment that he proclaimed the moral majority was dead.

“I think we are caught up in a cultural collapse of historic proportions, a collapse so great that it simply overwhelms politics,” he wrote in a letter to his supporters in 1999. He urged conservatives to drop out of politics and concentrate on fortifying conservative culture by building schools and other organizations.

In 2001 he was roundly attacked from the right and left for writing in an Easter letter to supporters that “Christ was crucified by the Jews.” One critic, a writer for a conservative publication, called him a “demented anti-Semite.” Weyrich said his comment was misconstrued and he apologized.

Although in constant pain, Weyrich remained actively committed to his cause through his last days, speaking on a panel before new members of Congress last week and writing letters of encouragement to fellow conservatives adrift in the political wilderness after the election of President-elect Barack Obama..

If he felt lost, it did not show. He continued to write a column on the website of the Free Congress Foundation: His latest piece, published Thursday, the day of his death, was titled “The Next Conservatism.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.