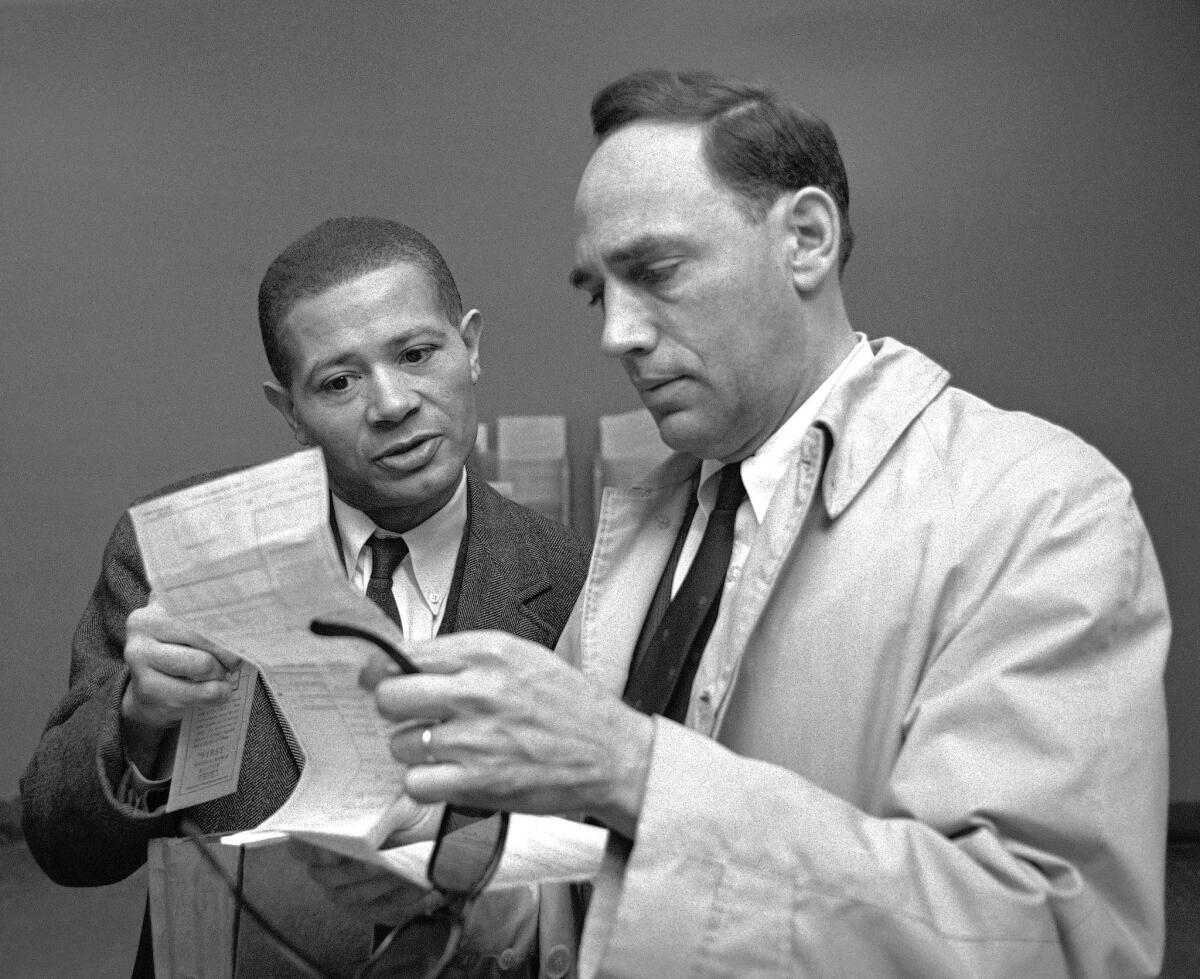

William Worthy dies at 92; journalist challenged U.S. policies

- Share via

Ignoring Cold War restrictions, journalist William Worthy had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1955 and made a news broadcast from Moscow, a rare opportunity for an American reporter. So the following year, when Communist China invited him on a month-long reporting trip, he quickly accepted.

He crossed the border from Hong Kong on Christmas Eve 1956, becoming the first American journalist to enter China in seven years, according to Time magazine. But his trip violated travel restrictions set by the U.S. State Department: It revoked his passport, setting off a legal battle that made headlines across the country.

Worthy, who again challenged U.S. policies when he went to Cuba without a passport in the early 1960s, died May 4 at a nursing home in Brewster, Mass., from complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his friend Michael Lindsey. He was 92.

His defiance of the travel ban led to a landmark federal case and inspired “The Ballad of William Worthy,” a 1960s protest song by folk singer Phil Ochs. In the early 1980s, Worthy made headlines again after a controversial reporting trip to Iran in the wake of the hostage crisis.

He was an obscure figure by the time Harvard University’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism honored him in 2008 with the Lyons Award for conscience and integrity.

“I would say he was very definitely an unsung hero,” said Bob Giles, former curator of the Nieman Foundation. “He took it on himself to go to places like Korea, Russia and China, where American journalists were not particularly welcome. He had access to Fidel Castro and other leading figures who were seen as enemies to the United States, reported on them and contributed to public understanding” of their leadership and political systems.

Worthy first came to wide attention in 1956 when, as a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American and CBS News, he was among 18 American journalists invited to China by Mao Tse-tung’s government. Most of the journalists declined the invitation except for Worthy and a team from Look magazine.

During the trip, Worthy interviewed future premier Chou En-lai as well as American prisoners captured during the Korean War. Back in the states, mainstream coverage of his entry into China reflected the prejudices of the time in pointed descriptions of him as “an American Negro” who had gone to the Communist country in defiance of U.S. authorities.

When he returned, he challenged the State Department’s denial of his passport, but the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the government’s decision, citing fears that a “blustering inquisitor ... can throw the world international neighborhood into turmoil.”

Undaunted, Worthy made several trips to Cuba in the early 1960s to interview Castro and report on race relations, which he found more favorable to blacks than in the United States. Upon his return, he was arrested and found guilty of entering the United States without valid documents.

“According to top civil liberties attorneys in this country ... I became the first person ever to be indicted for coming home,” Worthy wrote in the Catholic Worker newspaper in 1962.

His plight inspired Ochs, who featured the song about Worthy on his 1964 album “All the News That’s Fit to Sing”:

William Worthy isn’t worthy to enter our door,

He went down to Cuba, he’s not American anymore,

But somehow it is strange to hear the State Department say,

“You are living in the free world, in the free world you must stay.”

Worthy’s conviction was overturned by an appellate court in 1964, but he was not issued a new passport until 1968. In the intervening years, he continued to report from sensitive foreign destinations, including North Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia.

In 1981, he went to Iran as a freelance producer for CBS News, returning with copies of secret documents allegedly removed from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran by Iranian militants during the hostage crisis. The documents, which Worthy had purchased at a Tehran newsstand, had been published in several volumes that the journalist described as “something like those Bantam books on the Pentagon Papers” and had been widely circulated in Iran.

When Worthy and two technicians responsible for taping and sound for CBS landed in Boston, the books were confiscated by the FBI. The three journalists sued the U.S. government for the return of the material. In December 1982, the government agreed to pay them $16,000 to end the lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Insisting that Americans “have a right to know what’s going on in the world in their name,” Worthy provided copies of the documents to the Washington Post, which used them as the basis for a series, “Iran Documents Give Rare Glimpse of a CIA Enterprise.”

Born on July 7, 1921, Worthy grew up in a Boston household with activist parents. His father, William Sr., was a physician who helped start the city’s first black hospital. His mother, the former Mabel Posey, was an advocate for better schools and social services for blacks.

At Bates College, he wrote for the campus paper and earned a bachelor’s degree in 1942. He was a conscientious objector during World War II.

Never married, he is survived by a sister, Ruth.

He was a correspondent and columnist for the Baltimore Afro-American for three decades, starting in 1953, but also wrote for other publications, including Esquire, Harper’s and the Boston Globe. He was the author of a 1976 book about community action, “The Rape of Our Neighborhoods.”

He held positions at Boston University, Howard University and the University of Massachusetts, where he prodded students to think critically in a class he co-taught with Lindsey, a retired journalist.

“Everything with Bill was verify, verify, verify,” Lindsey said. “One of his favorite sayings was, ‘So you think your mother loves you because she said she did? Well, check it out.’ Students left with their mouths wide open.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.